The Expressive Effects of Bilateral Labor Agreements

Bilateral labor agreements (BLAs) aim to facilitate the movement of temporary migrant workers between countries. So far, studies of BLAs have focused on whether they have effects on migration flows. Despite countries entering hundreds of BLAs, evidence for their effects on migration flows remains limited. Yet, even if BLAs have limited material effects, they may still have important symbolic effects. On this topic, this Comment highlights BLAs’ potential to change rhetoric about international migration among heads of state. Drawing on an original empirical analysis focused on BLAs with the Philippines, the Comment analyzes how BLAs may influence leaders’ expressed attitudes toward international migration during United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) debates. Results reveal significant positive shifts in sentiment about international migration after countries form BLAs with the Philippines. The improved sentiment has a limited duration, however, diminishing after initial surges. Considering these findings, the Comment contributes to three bodies of legal scholarship, namely, those dealing with (1) the need for more social science research in international law, (2) the socioeconomic and political effects of BLAs, and (3) the utility of international agreements to constrain or prompt change in state action. Ultimately, the Comment calls for a comprehensive assessment of international agreements, recognizing their ability to affect not only intended outcomes but also high-profile symbolic outcomes.

Introduction

In 2012, Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf—then president of the Swiss Confederation—spoke on Switzerland’s behalf in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) General Debate. Widmer-Schlumpf stated that Switzerland faced “significant and pressing challenges” including “[c]limate change, food security, water scarcity, migration, organized crime, terrorism and the proliferation of weapons [all of which did] not halt at our borders.”1 Notably, Widmer-Schlumpf lumped international migration with famines, crime, and terrorism as a type of “challenge[], which threaten[s] entire regions.”2

Speaking before the same UNGA body five years later, Doris Leuthard—a subsequent president of the Swiss Confederation—similarly characterized international migration as a “challenge.”3 Indeed, the potential for challenge had been amplified since, as Leuthard noted, “[by] the end of 2016, there were [as] many displaced people in the world as there had been at the end of the Second World War.”4 But Leuthard maintained that, under her watch, “Switzerland [was] working to ensure that the [g]lobal [c]ompact for [safe, orderly and regular] [m]igration addresse[d] . . . not only the challenges [caused by international migration] but also [its] opportunities.”5

The slight difference in these perspectives on international migration—one mentioning only its potential to burden or threaten, the other noting both burden and potential benefit—could owe to many factors. The world changed a lot between 2012 and 2017. But curiously, it had changed in ways that one might expect to have made Leuthard, not Widmer-Schlumpf, more likely to emphasize international migration’s downsides. As Leuthard noted, for example, a sudden mass displacement of people left millions on Europe’s doorstep in the intervening years.6 Playing up the threat or burden of foreigners seems like the more obvious approach for a politician in 2017. This is especially true since Leuthard belonged to a right-of-center party7 for whom nativism became, between 2012 and 2017, even more popular politically.8 Indeed, in 2014, Switzerland had even voted to retreat from free movement agreements with the European Union in a development that “sent shockwaves” across the continent.9

This Comment argues that the type of rhetorical change observed in the case of Switzerland’s heads of state fits into a more general pattern observed among other countries in the period after they entered into bilateral labor agreements (BLAs). BLAs are arrangements “between . . . a host country and a source country . . . that specify the number and qualifications of temporary migrant workers that a receiving country is willing to admit[,] and a sending country is capable of sending.”10 Countries like Switzerland have increasingly entered BLAs as host countries “as a tool for the regulation and governance of short-term temporary labor migration.”11 In fact, Switzerland entered into a BLA with the Philippines in 2014, which was part of the period between Widmer-Schlumpf and Leuthard’s speeches.12

The little scholarship that has evaluated BLAs’ effects has largely focused on whether they increase migration flows and migration-related activities.13 This Comment argues that an important, but not yet considered, consequence of BLAs is their effect on attitudes and discourse about international migration. In fact, the ability of BLAs to shift discourse may provide an explanation for a positive change in sentiment regarding international migration among the heads of state in Switzerland and many of its peer countries that otherwise haven’t seemed particularly well-positioned to change.

Countries have entered into hundreds of BLAs in the past decade.14 Considering the potential of BLAs to benefit the receiving country, but also the potential for backlash, it is important to understand what effect such agreements might have on sentiment vis-à-vis international migration. Public sentiment toward different groups can translate into policy and societal treatment of those same groups.15 Focusing on political elites in this regard, as this Comment will, is particularly important not only because of political elites’ power to create and enforce law but also because they shape public opinion about the groups to whom the law applies.16

This Comment evaluates how BLAs, made with the Philippines in particular, affect heads of states’ expressed views on international migration in the context of UNGA debates. As the Comment describes in further detail below, focusing on the Philippines as a sending country is ideal because the Philippines (1) has exported considerable numbers of workers in the past 70 years; (2) has been extensively studied in research; (3) has become recognized as a migration model; and (4) has comprehensive BLA records with diverse receiving countries. The UNGA General Debate likewise presents an ideal setting to study discourse due to (1) its annual occurrence, allowing for regular sentiment assessment; (2) its formal and institutionalized setting, which ensures consistent discourse on topics and themes from year to year; and (3) its inclusion of all U.N. member states such that each country has an equal opportunity to speak to the same audience from the same platform. As the Comment notes below, such debates can provide a barometer of political elites’ sentiments vis-à-vis a wide range of issues.

This Comment’s focus on the connection between BLAs and discourse in UNGA debates allows for the Comment to make contributions to three bodies of legal scholarship. First, the Comment provides a direct response to legal scholars Daniel Abebe, Adam Chilton, and Tom Ginsburg’s recent call in a Chicago Journal of International Law symposium for more social science research in international law.17 In the past two decades, international law scholarship has increasingly taken an “empirical turn.”18 This Comment extends this research movement to the study of BLAs and addresses questions about the symbolic function of law. As the Comment will describe in detail below, it also makes novel methodological contributions with the potential to advance subsequent research in the social science of international law.

Second, the Comment expands knowledge of BLAs. The Comment specifically argues BLAs have expressive effects. As the Comment discusses in greater detail below, the intuition of “expressive” function of laws is that laws can influence behavior and attitudes not only through sanctions but also through “signaling the underlying attitudes of a community or society.”19 Consistent with this, the Comment’s analysis identifies a statistically significant shift in sentiment about international migration after countries enter BLAs with the Philippines. On average, entering into these BLAs appears to promote positive sentiment toward international migration. The improved sentiment, however, appears to have a shelf life of a few years. While BLAs with the Philippines appear to prompt an initial positive shift in sentiment, this effect wanes over time, eventually returning to pre-BLA levels.

Third, the Comment contributes to studies of international agreements more generally. A certain line of scholarship questions whether and what to extent such agreements have any effect.20 The Comment emphasizes the importance of not only the material consequences of agreements but also their symbolic consequences. Indeed, its findings suggest that, even if international agreements do not alter activities in an expected manner, such agreements may still have some non-negligible consequences for the discursive construction of groups governed and affected by the agreements. On hot-button global issues—such as international migration—knowing that such legal instruments can “lower the temperature” of escalatory and extreme rhetoric is important.21

The Comment proceeds in four parts. Part II discusses BLAs. It first walks through the potential reasons why countries might want to form BLAs. Then it discusses past and present uses of BLAs. Last, it summarizes existing empirical studies on the effects of BLAs. To fully understand the potential effects of BLAs, however, one must consider the expressive functions of law, which is the topic of Part III. Part III begins by touching on research on expressive effects generally, before highlighting research on the expressive effects of international law and research relevant to international migration. Part IV combines the insights from Parts II and III and brings them to bear on an empirical analysis. This Part first provides background on the Philippines, highlighting the factors that make it an ideal case study of a migrant-sending country in the context of BLAs. Part IV then discusses the data and key measures of the study and the results of its statistical analyses. Finally, Part IV summarizes the study’s findings and contextualizes them within three existing scholarly conversations. Part V concludes the Comment.

II. Bilateral Labor Agreements

A. Why BLAs?

BLAs are agreements between two countries that define the requirements and expectations for migration and employment. A typical “BLA may call for sending countries to pre-screen migrant workers before they depart, for receiving countries to give migrant workers certain protections during their deployment, and for both countries to keep records, share information, and resolve disputes that arise related to the cross-border movement of workers.”22 Most agreements make distinctions between labor-sending and labor-receiving countries.23

While agreements are mutual, each country’s motivations and anticipated benefits from BLAs are likely to differ. Receiving countries have several motivations and objectives. These countries seek to address the labor demands of various industries.24 They likely hope to manage both regular and irregular migration.25 They probably assume they will foster cultural and political ties with their co-signatory nations.26

Sending countries have different motivations and objectives. Maintaining access to labor markets is one such motivation.27 Politicians in these countries may see BLAs as a means to alleviate unemployment pressures within their borders.28 The agreements could also mean greater capital inflows in the form of remittances to people still in the sending country, which could spur economic growth and increase government revenue.29 Finally, the agreements can encourage the repatriation of migrants to mitigate the brain drain effects of more permanent forms of migration.30 Both labor-sending and labor-receiving countries may also be motivated to ensure that migration is a win-win-win exercise where both participating countries and migrants themselves win. That is, such agreements benefit not only sending and receiving countries but also migrants themselves, often in the form of added labor protections such as improving working conditions for migrants,31 negotiating fair employment contracts,32 and reducing the exploitation of migrant workers.33

B. Bilateral Labor Agreements Past and Present

For more than a century, countries have used agreements to govern labor migration. But the use of such agreements has waxed and waned alongside major economic and political developments. In the first part of the twentieth century, we see this pattern. In 1904, France and Italy signed what may have been the first agreement governing labor migration.34 Following the first World War, France later helped create what would become a model agreement in its treaty with Poland in 1919.35 This agreement set protocols for the admission, residency, and basic labor standards for foreign workers, as well as the recruitment and transfer processes between labor markets.36 It created a regulated migration channel that shifted recruitment from individual choice to state control, allowing both countries to select candidates before migration.37 This framework also ensured that Polish migrants were expected to receive the same labor standards as French workers, reinforcing the principle of equal treatment.38 Over the next two decades, countries signed a total of about 24 such agreements.39

The BLA, as currently understood, emerged primarily following World War II.

[M]any of the European states that were ravaged by World War II, including Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany, signed treaties immediately after the war [as sending states], when unemployment was high. When their economies began to grow again and unemployment fell below structural levels, the Netherlands and Germany became receiving states.40

Scholarly research indicates that this post-war period of BLA formation continued for nearly three decades.41

Around 1974, a new phase for BLAs began. A global economic downturn reduced the demand for labor and resulted in fewer total BLAs.42 Scholars point to economic shocks, including the 1973-74 oil crisis, resulting in the discontinuation of many BLAs over the next decade and a half.43 While the total number of BLAs declined globally during this period, they became increasingly popular in the countries that benefited from the oil crisis, namely wealthy Middle Eastern oil states.44

The final and current phase for BLAs began in 1990.45 This period has been characterized by a resurgence of BLAs sparked by the Cold War’s end, which promoted a rapid increase in openness to trade and migration.46 The last three decades have witnessed an incredible growth in BLA activity. In total, 472 BLAs were signed in the 45 years between 1945 and 1989, averaging approximately 10.5 per year.47 The period from 1990 to 2020 saw the signing of 744 BLAs in just 31 years, averaging 24 per year.48

These historical trends illustrate just how closely the creation of BLAs and similar agreements is tied to global political and economic forces. Such forces themselves likely shape attitudes toward international migration, as well as perceptions about its costs and benefits. For this reason, it is worth considering why the true number of current or historical BLAs is hard to estimate. Countries may enter into informal agreements when they want to obscure what they are doing. Political scientists Tijana Lujic and Margaret Peters argue that politicians use such informal agreements and obfuscate information on BLAs when it seems that BLAs would be politically unpopular and/or unlikely to be officially ratified.49 Thus, because of the potential for BLAs to become a political liability, some countries may only enter formal agreements when they want to officially lock in a policy.50 “BLAs, by design, are a carve-out for a particular interest group.”51 Such formal agreements may be helpful when, accordingly, policymakers want to publicly signal support for migrant laborers as a particular interest group.

C. Empirical Studies on the Consequences of BLAs

To understand whether BLAs might have expressive effects, it may be insightful to consider what effects BLAs have on other outcomes according to existing scholarship. Understanding these effects on other outcomes is important because such effects themselves might be a means through which BLAs affect sentiment. For example, if BLAs cause economic growth in a country, then one might expect politicians to speak more favorably about international migration after they see evidence of some benefit connected to BLAs. It is helpful, accordingly, to distinguish between the intended and unintended effects of BLAs.

Regarding intended effects, BLA host-country economies appear to improve, at least by some metrics. Researchers have found that the formation of a BLA has a positive and statistically significant effect on GDP per capita.52 For example, based on estimates from the data used for this Comment, the GDP of a country increases by between 1.5 and 2 percent in the year after it signs a BLA with the Philippines.53 Whether this effect results from the allocation of migrant laborers to in-demand areas of the economy is less clear, especially given the findings about the effects of BLAs on migration and trade.54 But, the history of individual BLAs suggest that it is a possibility. The U.S.-Mexico “Bracero” program, for example, clearly helped fill a labor shortage in agriculture during WWII.55 However, whether this generalizes beyond a single BLA during a specific historical era remains unclear.

Results are mixed as to whether the BLAs increase migration flows. Legal scholars Adam Chilton and Eric Posner note that while there is a positive correlation between the existence of a BLA and an increase in migration, there was insufficient evidence to disprove reverse causation, namely, that “rising migration causes countries to enter into BLAs.”56 In methodologically more sophisticated case studies of the Philippines as a sending country, Adam Chilton, Bartosz Woda, and public policy researcher Brianna O’Steen separately find no empirical evidence that these treaties drive migration.57

There is little evidence supporting the notion that BLAs improve labor conditions in the way that some countries might intend. Chilton and Woda have noted that, even though BLAs have recently proliferated, very few of them contain the types of protections advocated for by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and other parties interested in worker wellbeing.58 In a case study of migrant workers in Israel’s construction industry, researchers Yoram Ida, Gal Talit, and Assaf Meydani find that while BLAs help reduce the exploitation of migrants in the form of brokerage fees, they cannot determine whether the agreements contribute to the protection of the rights of the employees.59

Regarding unintended effects, BLAs have a positive and significant effect on trade and entry to subsequent BLAs. Authors have found that the formation of BLAs predicts a significant subsequent increase in “aggregate exports and exports of differentiated goods (i.e., chemicals and miscellaneous manufactured goods).”60 Perhaps this is not an entirely unexpected result given the argument that countries sign BLAs for goodwill motivations. But BLAs seem to beget more BLAs. Chilton and Woda find that signing one BLA makes a country more than six times as likely to sign another BLA (compared to countries that haven’t signed any BLAs at a given time).61

There may also be some negative unintended effects of BLAs. Scholars Jenna Hennebry and her collaborators note that BLAs may amplify existing gender disparities in the workforce.62 Hennebry and colleagues argue that BLAs may reduce both sending and receiving countries’ commitment to protecting the rights and wellbeing of migrants, especially women.63 They root this lack of protection in “the gendered division of labor where women are overrepresented in low-wage, unprotected types of work[,]” thus disproportionately disempowering female migrants who stand to benefit the most from rights protections.64

In sum, empirical studies of BLAs suggested a few things about their effects. For one, BLAs appear to positively affect host-country economies, particularly GDP per capita, but the connection to migrant labor allocation remains unclear. Studies reach mixed findings on whether BLAs increase migration flows, and little evidence supports the idea that BLAs improve labor conditions as intended by some countries. But the formation of BLAs predicts subsequent increases in aggregate exports. Research also suggests a tendency for countries to sign more BLAs once they have entered into one, and it touches upon the potential negative effects of BLAs, particularly in relation to gender disparities in labor protections.

III. Expressive Effects of Law

A. Expressive Effects Generally

That laws change behavior seems obvious. But scholars have argued that laws can have behavioral consequences, not only through enforcement mechanisms—such as fines or penalties—but also through symbolic, communicative channels.65 The basic argument is that laws have “expressive effects” because they imply normative conclusions about forbidden behaviors and such messaging influences individuals’ moral evaluations of those behaviors.66 Accordingly, people follow laws because they internalize the moral code implicit within the spirit of the law, rather than following laws because they fear punishment.67

Some have argued that laws don’t only change behavior, but also hearts and minds. Beyond encouraging adherence to laws, scholarship has also argued that laws can change “judgments of other people” by shifting the “reputational utility” of particular behaviors.68 As an example based on this intuition, legislative bans on conversion therapy are not only important because they reduce the incidence of the practice but also because they can “reverse a historical narrative that cast gays and lesbians as dangerous to children.”69 Law can thus change both behaviors and the reputations of categories of people associated with behaviors.

The foregoing changes occur in both negative and positive directions. For example, psychologists Sara Burke and Roseanna Sommers found in their recent study that learning of discrimination’s illegality not only increases the perception of potential consequences for discriminatory actions by employers but also prompts some individuals to express fewer biased beliefs and develop stronger interpersonal bonds with members of the affected group.70 On the contrary, when individuals are informed that the law permits discrimination against a particular group, it can legitimize and encourage more biased attitudes.71

Thus, the expressive effects perspective suggests that laws communicate normative conclusions about prohibited behaviors, which influence individuals’ moral evaluations.72 The argument posits that people follow laws not solely out of fear of punishment but also because they internalize the moral code embedded within the spirit of the law.73 Moreover, laws are proposed to have the capacity to shape judgments of others. Legal changes can have both positive and negative effects. Examples suggest that knowledge of anti-discrimination laws not only influences perceptions of potential consequences but also leads to reduced biased beliefs and strengthened interpersonal bonds.74 Conversely, laws permitting discrimination may legitimize and reinforce biased attitudes.75

B. Expressive Effects of International Law

Some evidence exists that international law can have expressive effects too. The “expressive value” of international human rights law seems intuitive insofar as this type of law represents a relatively low-cost means through which “states make a public commitment to specific norms or values.”76

Legal scholars Alex Geisinger and Michael Stein, for example, have applied an expressive law framework to the formation of international treaties, specifically human rights treaties.77 They set out to understand the forces that motivate the creation of, and compliance with, treaties and how “normative pressure” may influence States to alter both their behavior and beliefs.78 Geisinger and Stein begin with the “need-reinforcement principle,” which provides a basis for understanding how a “desire for esteem” from other countries influences a state’s assessment of whether to enter into an international legal regime.79 This principle can then be used to understand how international legal regimes become internalized norms within a country, thereby shaping compliance with international law. This compliance is not only a result of the threat of sanctions but also a change in the country’s own “internal values.”80 When a legal regime is first implemented, the relevant norm may at that point be unknown, or at least uncertain.81 However, there is increased certainty as the norm created by the legal regime is announced. Subsequently, more states act in accordance with the norm, and a “corresponding increase in the esteem” a state receives as they adopt the norm occurs.82 This “norm cascade” continues until the norm “becomes entrenched in the fabric of international society.”83

Beyond state actors, some research suggests that international law can reshape the attitudes of individual citizens. Adam Chilton and Katerina Linos performed a recent comprehensive review of research on whether international law can “inform and change individual preferences” among citizens of different countries.84 The authors discuss empirical evidence that international law has changed public opinion by a nontrivial percentage, especially in the area of human rights.85 However, they indicate that while international law seems to “shift public opinion in the expected direction,” there are limitations in the existing research.86 Such limitations are “empirical problems” in studies linking public opinion and international law, the fact that there is no “consistent theory for why international law may change opinion,”87 and the “limited evidence linking changes in public opinion to concrete changes in policy.”88

Thus, the formation of treaties, particularly in the realm of human rights, has been a key area for understanding the expressive effects of international law. States seek esteem from other states, driving their decision to enter into international legal regimes. The internalization of legal norms holds the capacity to change behavior and beliefs beyond the threat of sanctions. Certain norms gain increased certainty and esteem until they become entrenched in international society. Some research suggests that international law can shape individual preferences, although certain empirical and theoretical limitations exist.

C. Expressive Effects of International Law vis-à-vis International Migration

Considering these findings, one might expect international law to have expressive effects on attitudes toward international migration. While no study has answered this question in the context of BLAs, several studies provide helpful insights. On the one hand, pro-migrant laws seem to encourage pro-migrant sentiment. A study of Australia, India, and the U.S. found that reminding individuals that international law supports the acceptance of refugees can reduce support for restrictive refugee policies.89 A similar study, focusing only on Australia, found that most people strongly oppose restrictive refugee policies if they found that such policies violate international law.90

On the other hand, restrictive migration laws tend to encourage anti-migrant sentiment. Research in the context of the United States has found that laws targeting undocumented immigration have the effect of increasing anti-immigrant or racist sentiment.91 Following the rollout of a restrictive immigration enforcement law in Arizona, for example, sociologist René Flores found that Arizonans’ online discourse about “immigrants, Mexicans, and Hispanics” became substantially more negative.92 Likewise, law and society scholar Emily Ryo conducted an experiment in which people were randomly exposed to anti-immigrant laws and found that such exposure correlated with higher rates of participants agreeing with the statements “that Latinos are unintelligent and law-breaking.”93

Laws that seem pro- and anti-immigrant, accordingly, appear to have a predictable effect of softening/hardening attitudes toward international migration and migrants. But interestingly, even laws that are presumably pro-international migration or that protect the rights of international migrants may increase negative attitudes toward international migration. Research has found that reiterating the government’s obligation, as stipulated in the Refugee Convention, to admit refugees can provoke a backlash and result in reduced backing for refugee admission.94 Similarly, research on the Trump administration’s family-separation policy found that informing individuals about the policy’s unconstitutionality led to a boost in support for the policy, specifically when the issue was prominently featured in the media.95 The same research further observed that international law did not exert a similar influence on public sentiment vis-à-vis the family-separation policy.96

It is possible to imagine that BLAs, accordingly, could have both positive and negative expressive effects. On the one hand, BLAs, which presumably promote pro-migrant principles and emphasize adherence to international norms, may foster a climate of openness and support for international migration. On the other hand, they may create backlash. Indeed, as Lujic and Peters have argued, some politicians suspect that BLAs can be politically unpopular.97 The U.S.-Mexico Bracero agreement, for example, faced considerable pushback from U.S. labor unions who “worried the imported labor would undermine the wages, working conditions, and employment opportunities of domestic . . . laborers.”98

In sum, evidence suggests that international law influences attitudes toward international migration. Pro-migrant laws, aligning with international norms, tend to promote favorable sentiments, while laws targeting undocumented immigration can increase anti-immigrant feelings. Interestingly, even ostensibly pro-international migration laws, such as those protecting refugee rights, may unexpectedly evoke negative attitudes. The complex dynamics of international law’s impact on public sentiment make it unclear, from an ex ante perspective, whether BLAs ought to promote positive or negative sentiment vis-à-vis international migration. Thus, empirically testing the effect of BLAs can help resolve the uncertainty on this question. Testing this can also contribute to broader conversations about the expressive effects of international law by helping to establish the boundary conditions under which previous findings may or may not apply.

IV. Empirical Study: The Philippines and its BLA Cosignatories

A. About the Case: Countries Signing BLAs with the Philippines

To understand the effects of entering BLAs, this Comment focuses on the Philippines as a sending country between the years 1970 and 2017. The Philippines is an ideal case study for several reasons. First, it has been a consistent labor-exporting country throughout all phases of migration and BLA ratification.99 Second, it has been heavily studied as an archetypal sending country in past scholarship.100 Indeed, other countries tout the Philippines as a model for global migration.101 Third, the Philippines has signed BLAs with a wide range of low-, middle-, and high-income receiving countries. Fourth, the Philippines has complete BLA records.

Like BLAs, the Philippines has its own political and economic history. The emergence of overseas employment in the Philippines took place roughly between 1965 and 1986.102 A debt crisis during Ferdinand Marcos’ regime created economic conditions that made emigration more desirable.103 A need arose to address surplus labor supply and civil unrest under martial law.104 Accordingly, the Marcos administration developed a foreign policy strategy that it referred to as “development diplomacy.”105 The strategy focused on finding, establishing, and formalizing international labor markets for Filipino workers.106

The Philippines formalized its labor export policy in 1974.107 As part of this, the country began to initiate negotiations of bilateral agreements with other nations to regulate temporary migration.108 The Overseas Employment Program was incorporated into the Philippine Labor Code, marking the first formalization of the national labor export policy.109

Since then, Filipinos have had success finding overseas employment in a wide range of regions and economic sectors through to the present. Historically and currently, Filipino men have found employment in construction in Middle Eastern countries with growing economies fueled by oil investments in infrastructure.110 Filipina women started migrating in the 1970s, primarily as English-speaking teachers.111 Demand for Filipina labor has surged since the 1970s, particularly in the health, sales, and domestic service sectors of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.112 In essence, the evolving landscape of Filipino overseas employment reflects a dynamic response to domestic and global economic shifts, with Filipinos and Filipinas contributing significantly to various sectors in countries worldwide. This marks a testament to the ability of the Filipino model of exporting labor in different types of work and to consistently adapt.

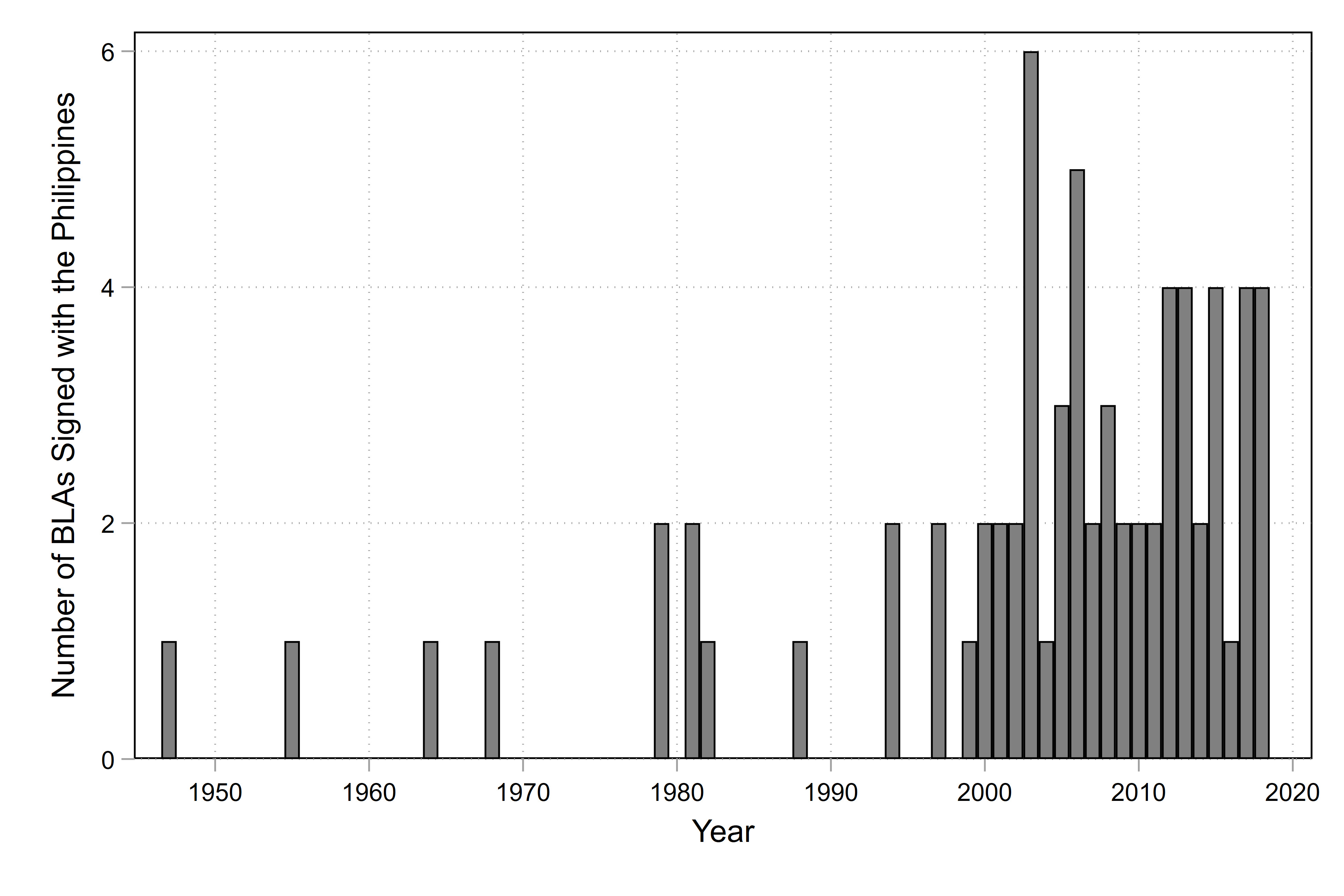

To provide a sense of how these trends map onto formal agreements, Table 1 contains a list of BLAs signed by the Philippines between 1947 and 2018. This list comes from Chilton and collaborators’ database.113 Figure 1 plots the distribution of these BLAs over time. Together Table 1 and Figure 1 illustrate a few striking patterns about the distribution and spacing of BLAs. First, while some BLAs predate even the Marcos regime, Figure 1 shows that the vast majority of BLAs with the Philippines have been signed in the period since the end of the Cold War (i.e., 1992 through the present). Second and relatedly, over time, Figure 1 and Table 1 show that the amount of time that has passed between each BLA signing has decreased considerably. For example, eight years passed between the first and second BLA (signed in 1947 and 1955, respectively). In the recent past, however, no more than a year has gone by without the Philippines signing a new agreement. Indeed, in many recent years, multiple countries have signed BLAs with the Philippines. Third, Figure 1 shows that in more recent years starting in 2004, the average number of BLAs signed with the Philippines is between three and five. Fourth, many countries are serial or repeat cosignatories to these BLAs. South Korea has been the cosignatory seven times; Canada six times; Jordan and Taiwan five times. Six other countries have cosigned three or four times. Eight countries have cosigned twice. Fifth, the geography of cosignatory countries covers a wide range of regions. The Americas, Asia, Europe, and North Africa all have multiple countries on the list.

Figure 1: Count of BLAs Signed with the Philippines, 1947–2018

| Year | Countries |

|---|---|

| 1947 | United States of America |

| 1955 | United Kingdom |

| 1964 | West Germany |

| 1968 | United States of America |

| 1979 | Libya, Papua New Guinea |

| 1981 | Jordan, Qatar |

| 1982 | Iraq |

| 1988 | Jordan |

| 1994 | Northern Mariana Islands, United States of America |

| 1997 | Kuwait, Qatar |

| 1999 | Taiwan |

| 2000 | Northern Mariana Islands, United States of America |

| 2001 | Norway, Taiwan |

| 2002 | Switzerland, United Kingdom |

| 2003 | Bahrain, Indonesia, Japan, Norway, Taiwan, United Kingdom |

| 2004 | South Korea |

| 2005 | Laos, Saudi Arabia, South Korea |

| 2006 | Canada, Japan, Libya, South Korea, Spain |

| 2007 | Bahrain, United Arab Emirates |

| 2008 | Canada, New Zealand, Qatar |

| 2009 | Japan, South Korea |

| 2010 | Canada, Jordan |

| 2011 | South Korea, Taiwan |

| 2012 | Canada, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon |

| 2013 | Canada, Germany, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia |

| 2014 | South Korea, Switzerland |

| 2015 | Canada, Italy, New Zealand, Taiwan |

| 2016 | Cambodia |

| 2017 | Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, United Arab Emirates |

| 2018 | China, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait |

B. Data, Analysis, and Discussion

1. Data

This analysis is based largely on datasets previously compiled for two other studies. Political scientists Beth Simmons and Robert Shaffer created the first dataset for their recent study.114 This dataset uses texts from United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) annual debates.115 These records offer a barometer of state and world opinion on various topics for the years between 1970 and 2017. Given the range of years is smaller than that included in the BLA set, analysis is restricted to this set of years.

Adam Chilton, Eric Posner, and Bartek Woda created the second dataset.116 While it does not capture the entire universe of all BLAs ever signed,117 it contains the most comprehensive list of BLAs published to date.118 For the reasons mentioned earlier, the analytic sample subsets the list to include only BLAs signed with the Philippines.

a) Outcome Variable

The outcome variable of interest is Sentiment about International Migration (SAIM). This is a measure of a given country’s leader’s sentiment about international migration in UNGA General Debate sessions in a given year. Focusing on the setting of the General Debate can prove insightful for a few reasons. First, the General Debate takes place every year. 119 This means that it allows us to consider measures of sentiment collected in regular intervals. Second, this setting is formal and institutionalized, which can help make the types of topics and discourse likely to occur from speaker to speaker and from year to year fairly consistent.120 Third, the General Debate includes all U.N. member states, which means that each country gets the same opportunity to speak from the same platform to the same audience, namely, the Assembly.121

The true SAIM measure relies on sentiment analysis, which uses natural language processing and machine learning techniques to analyze and determine the sentiment expressed in a piece of text, such as positive, negative, or neutral, providing insights into the subjective opinions and emotions conveyed.122

Excerpts from Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf and Doris Leuthard’s UNGA speeches are illustrative here. Table 2 contains the excerpts along with assigned scores for positive, neutral, negative, and overall sentiment. In the excerpt by Widmer-Schlumpf, the language used emphasizes the severity of global challenges, including climate change, food security, and terrorism. Phrases like “do not halt at our borders”123 and “threaten entire regions”124 contribute to negative sentiment, suggesting a recognition of the serious and potentially far-reaching consequences of these issues. While there is a factual presentation of the global challenges, the lack of explicit positive language results in a moderately negative overall sentiment.

| Widmer-Schlumpf | Leuthard | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excerpts | “Climate change, food security, water scarcity, migration, organised crime, terrorism and the proliferation of weapons do not halt at our borders. These are global challenges, which threaten entire regions.”125 | “Switzerland is working to ensure that the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration addresses not only the challenges caused by international migration but also its opportunities.”126 | |

| Scores | Positive | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Neutral | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Negative | -0.6 | 0.0 | |

| Overall | -0.4 (moderately negative) | 0.5 (neutral to positive) | |

Leuthard’s excerpt, on the other hand, conveys a positive sentiment. The language used indicates a proactive and constructive approach to international migration issues. Phrases like “working to ensure”127 and the emphasis on addressing both challenges and opportunities128 contribute to a positive score. The mention of opportunities in addition to challenges indicates a more balanced and optimistic perspective, resulting in an overall sentiment leaning toward the positive end of the scale.

These excerpts exemplify the general approach of constructing SAIM. The measure averages these scores across all paragraphs discussing migration/borders in UNGA debates for a given country’s head of state in a given year. Higher values indicate more positive sentiments regarding international migration while lower values indicate more negative sentiments. This measure varies over time within countries, meaning that a given country’s SAIM can be completely different from one year to the next.

b) Explanatory Variable

The key explanatory variable indicates whether a given country entered into a BLA with the Philippines in a given year. All countries that have eventually entered into a BLA with the Philippines are considered part of the “Treatment Group.” All countries that have never entered a BLA with the Philippines are part of the “Control Group.” To allow for the effect of being in the Treatment Group to vary as a function of time before and after the beginning of a BLA, the results provide estimates in the form of time to/since the adoption of BLA. If one thinks that BLAs have a distinct effect on SAIM, one would expect an observable and statistically significant change—either positive or negative—in the years following the formation of a BLA. The analysis section evaluates the effect of belonging to the Treatment Group within what is called a “panel event study” framework, which entails looking at the period prior to and after the formation of BLA.129 The Comment explains the intuition behind this approach in greater detail in the Analysis subsection.

c) Control Variables

To avoid confounding relationships, the analysis estimates models that adjust for the effects of the following control variables:

- GDP: this is a World Bank measure of gross domestic product per capita in a given country and year (inflation-adjusted);130

- Population: this is a World Bank measure of a given country’s inhabitants in a given year;131

- Civil Disputes: this is a Center for Systemic Peace132 measure of the count of major episodes of intra-state political violence in all states sharing a land border with a given state in a given year, resulting in at least 500 directly related deaths over the course of the episode;

- Interstate Disputes: this is a Center for Systemic Peace measure of the count of major episodes of interstate political violence in all states sharing a land border with a given state in a given year, resulting in at least 500 directly related deaths over the course of the episode;133

- Net Migration: this is a World Bank measure of total number of immigrants less the annual number of emigrants, including both citizens and noncitizens;134

- Economic Globalization: this is a KOF Swiss Economic Institute measure of the degree of integration into the world economy, with emphasis on trade (goods, services, partner diversity) and financial (foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, international debt, reserves, and foreign income) integration indicators; 135

- Political Globalization: this is a KOF Globalization Index based on embassies, peacekeeping participation, and international NGOs.136

2. Analysis

a) Analytical Approach

All of the analyses are at the level of country years. The Findings subsection first describes descriptive statistics on the distribution of the SAIM measure. The section explores how SAIM varies over time and across countries.

The Findings subsection then compares Treatment group and Control Group countries within a panel event study framework. The intuition behind this approach is to “use[] data covering a panel of observations (such as [countries]) over time, . . . to estimate the impact of some event that occurs, or ‘switches on’ in certain units and certain time periods.”137 In this case, the event that will switch on Treatment group countries is the formation of a BLA with the Philippines. The models then take the countries “in which the . . . event does not occur or has not yet occurred” as counterfactuals to the Treatment group.138 Then, “by considering the variation in outcomes around the [formation of a BLA] compared with a baseline [pre-BLA] reference period, one can estimate both event leads and lags, which allows for a clear visual representation of the event’s causal impact.”139

The Robustness Checks subsection then describes a series of tests implemented to ensure that the findings of the analysis are not sensitive to assumptions made by choosing a specific statistical model.

b) Results

Table 3 displays descriptive statistics for country years included in the sample. There are a few key details to note when interpreting the results. For the outcome variable—SAIM—Table 3 shows that the mean and median are virtually identical (at -0.405 and -0.406, respectively). The minimum value—indicating the lowest sentiment toward international migration—for this measure is -0.487. The maximum value is -0.297. The standard deviation is .024. What is striking about the distribution of these variables is how negative it is. This suggests that when discourse about international migration appears in UNGA General Debates, speakers rarely discuss the topic in a positive light.

| Variable | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable: Sentiment about Int. Migration | -.405 | -.406 | .024 | -.487 | -.297 |

| Explanatory Variable: Ever Have BLA with Philippines | .056 | 0 | .238 | 0 | 1 |

Notes: N = 2,692 country years. SD = Standard Deviation

Regarding the main explanatory variable, the mean from Table 3 indicates that only 5.6 percent of all country years (or a total of 24 countries) are considered part of the Treatment Group.

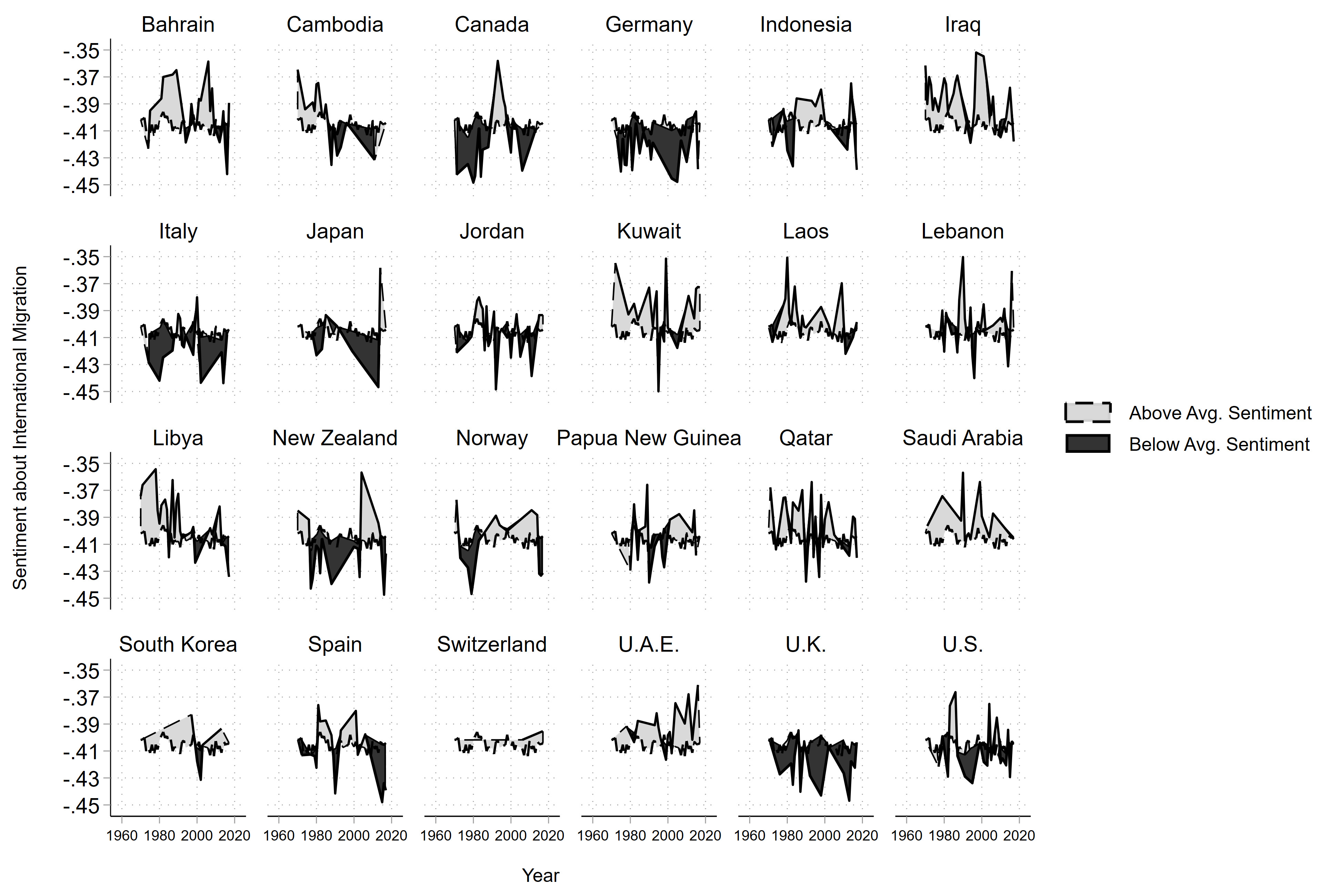

Figure 2 plots the SAIM measure over time for all the countries included in the Treatment Group. If a country’s SAIM is above the average for all countries in a given year, Figure 2 shades in light gray the region between the country’s sentiment and the global average. If a country’s SAIM is below the average, Figure 2 shades the region black.

Figure 2: Sentiment about International Migration for Treatment Group Countries, 1970–2017

Figure 2 shows a few distinct patterns. First, there is incredible variation over time in SAIM, suggesting that the way a given country’s leaders speak about international migration can change considerably from one year to the next. Second, some countries have consistently above average values for SAIM. Examples of countries with higher values on average include Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Laos, Libya, Papa New Guinea, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United Arab Emirates. Third, other countries have more of a mixed record—indicating below and above-average values—on SAIM. Examples of these include Cambodia, Canada, Indonesia, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and the United States. Finally, some countries have consistently lower-than-average values on SAIM. Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom fall into this group. The fact that the first list is the longest suggests that the type of country that eventually enters a BLA with the Philippines is likely to generally have higher-than-average values on SAIM in the first place.

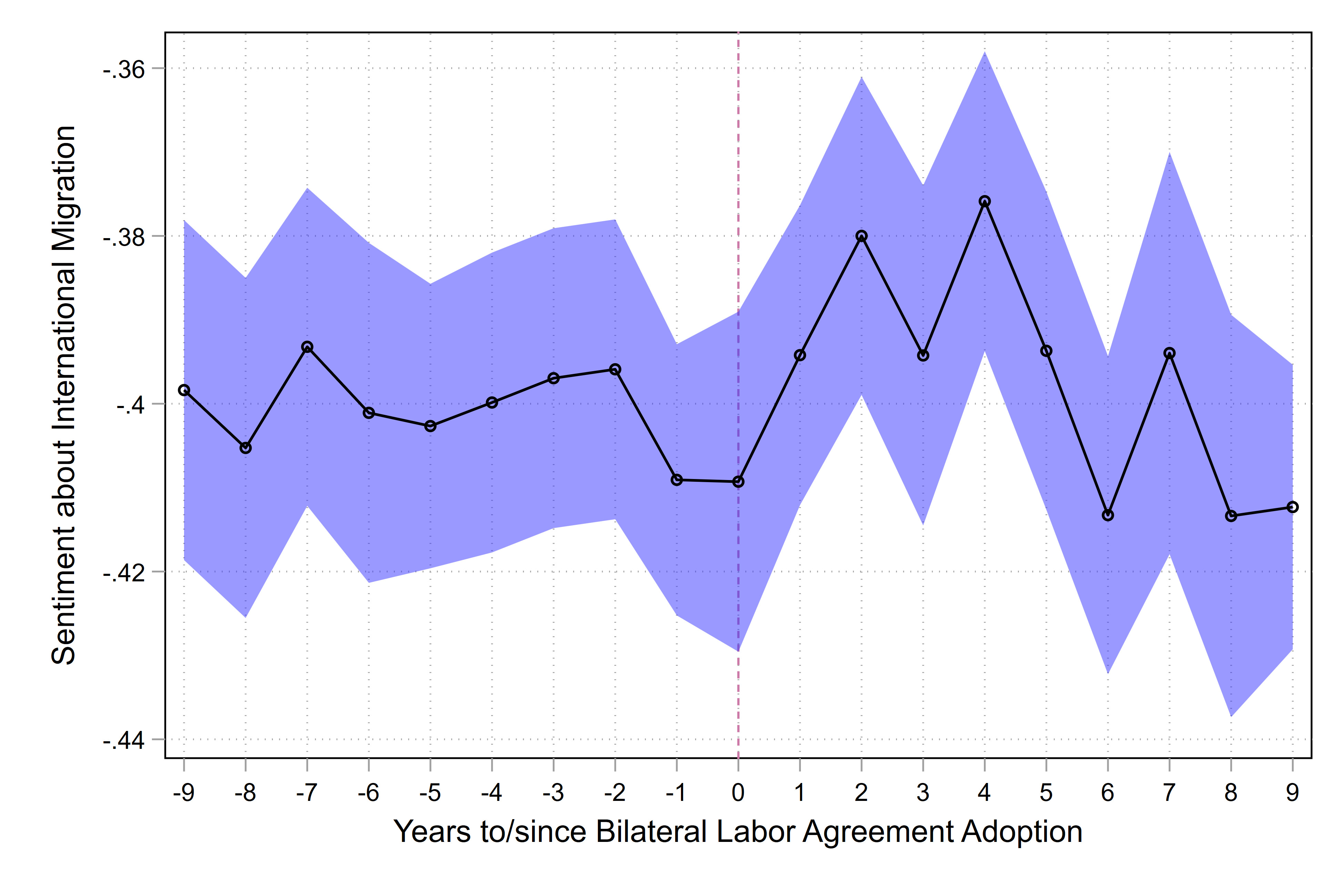

Figure 3 plots the average SAIM for countries in the Treatment Group with 95 percent confidence intervals relative to the time of their formation of a BLA with the Philippines. Like Figure 2, Figure 3 shows that there is quite a bit of variation in the average SAIM over time. Notably, however, Figure 3 shows that there is a non-random pattern to this variation. Following the formation of a BLA with the Philippines, there is a considerable increase in SAIM followed by an eventual decrease that roughly returns to pre-BLA levels. This suggests that BLAs may have some effect on SAIM in the years following their formation, but that effect is short-lived. To tell more definitively would require a dive into multivariable statistical analysis, which this Comment does below.

Figure 3: Sentiment about International Migration for Treatment Group Countries Relative to BLA Adoption, with 95 percent Confidence Intervals

Table 4 displays the average marginal effects (AMEs) of being in the Treatment Group compared to the Control Group in relation to the timing for the BLA adoption for a given country. AMEs in the context of the regression models estimated here compare the average change in the SAIM associated with a one-unit change in the explanatory variable of interest (i.e., being in the Treatment group) while holding all other variables constant. In the context of a Treatment group versus a Control group, the AME quantifies the average impact of being in the Treatment group on SAIM, accounting for the effects of other control variables in the model. It provides a measure of the average change in the level of SAIM for the treated countries compared to the control countries, considering the combined influence of all variables in the regression model.

Table 4 contains a few other pieces of information. The second column—labeled Model (1)—shows these effects not taking into account any control variables. The third column—Model (2)—shows these effects taking into account year and country fixed effects (FEs). Controlling for year and country FEs helps obtain more accurate, reliable, and interpretable estimates of a BLA’s effect by accounting for temporal trends and cross-country differences while minimizing bias in the analysis. Year FEs account for changes that occur over time, such as economic fluctuations, technological advancements, or evolving societal norms, which could influence the outcome of interest. By including these FEs, one can distinguish a BLA’s impact from general time-related trends. Country FEs control for unobserved heterogeneity across different countries that might affect SAIM. These could include cultural differences, legal systems, or country-specific policies unrelated to the one under study. For example, some of the countries in study do not have elected governments, and it is plausible that political elites in these countries may feel less constrained to change official discourse about international migration, one way or the other, to appeal to popular sentiments. Political elites who are subject to the electoral process, on the other hand, may have to behave more strategically. Controlling for country FEs, accordingly, isolates the specific impact of BLAs from these inherent differences. The fourth column—Model (3)—shows these effects taking into account year and country fixed effects and all control variables. The asterisks next to effect sizes indicate the level of statistical significance of the effect size.

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years until/since BLA Adoption | -9 | 0.0071585 | 0.0083877 | 0.0082792 |

| -8 | 0.000262 | -0.0005481 | -0.0027437 | |

| -7 | 0.0123171 | 0.0134749 | 0.0134743 | |

| -6 | 0.0044427 | 0.0067898 | 0.0113449 | |

| -5 | 0.0028703 | 0.0020504 | 0.0049967 | |

| -4 | 0.0056737 | 0.0057994 | 0.0092747 | |

| -3 | 0.0085742 | 0.0083498 | 0.00983 | |

| -2 | 0.0096324 | 0.0107793 | 0.0128474 | |

| -1 | -0.0035436 | -0.0034311 | -0.0088475 | |

| Adoption Year | -0.0037637 | -0.0028733 | -0.0046686 | |

| 1 | 0.0113185* | 0.0168419* | 0.0173835 | |

| 2 | 0.0255379** | 0.0233301** | 0.0247229** | |

| 3 | 0.0212833* | 0.0194824* | 0.0186561 | |

| 4 | 0.0296723*** | 0.0309974*** | 0.0315505*** | |

| 5 | 0.0118403* | 0.0100128 | 0.0082862 | |

| 6 | -0.0077521 | -0.0054457 | -0.00141 | |

| 7 | 0.0115717 | 0.0143981 | 0.0189817 | |

| 8 | -0.0078478 | -0.0070505 | -0.0148444 | |

| 9 | -0.006783 | -0.0050664 | -0.0016267 | |

| Year FEs? | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Country FEs? | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Controls? | No | No | Yes | |

Notes: N = 2,692 country years. FEs = Fixed Effects. Controls include measures of: GDP, Population, Civil Disputes, Interstate Disputes, Net Migration, Economic Globalization, Political Globalization

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

Table 4 shows that regardless of the number of controls included, there is an increase in SAIM in the years following the adoption of a BLA with the Philippines. This indicates that the discourse about international migration becomes more positive on average in the years following a country’s entry into a BLA with the Philippines, which is consistent with the hypothesis that BLAs have expressive effects. Models (1), (2), and (3) all indicate that in the four years following the formation of a BLA there is a statistically significant increase in SAIM. Model (1) shows a significant increase in the fifth year after a BLA’s adoption, but this effect disappears once we adjust for the effect of control variables.140

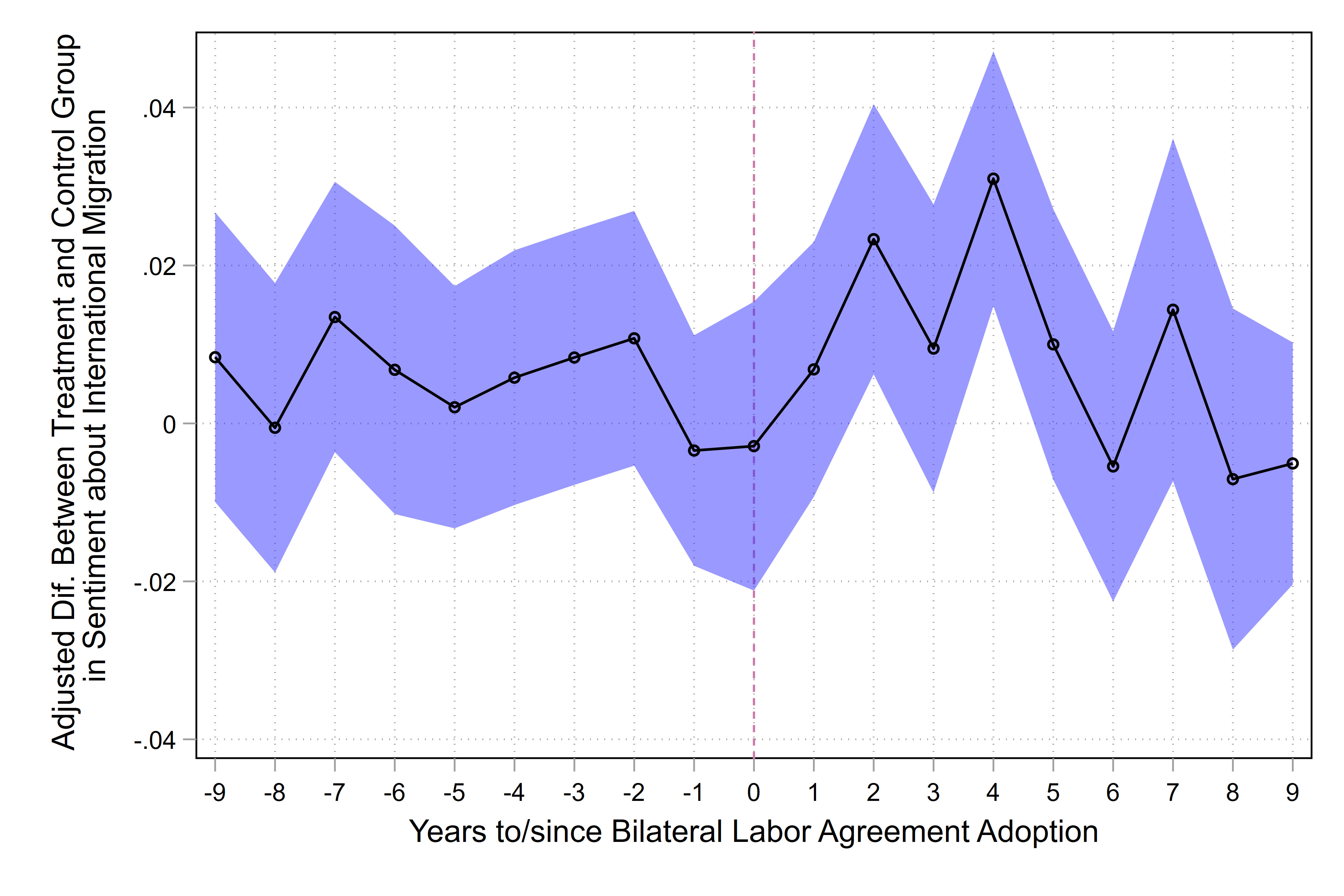

Figure 4 plots the average marginal effect of being in the Treatment Group on SAIM compared to the Control Group with 95 percent confidence intervals relative to the time of their formation of a BLA with the Philippines. These effects are estimated after taking into account control variables and fixed effects for years and countries. Hence, they are “adjusted” effects. Like Figure 3 and Table 4, Figure 4 shows that there is a non-random pattern to this variation. Following the formation of a BLA with the Philippines, there is a distinct increase in SAIM followed by an eventual decrease that roughly returns to pre-BLA levels.

Figure 4: Adjusted Difference between Treatment and Control Group in Sentiment about International Migration Relative BLA Adoption, with 95 Percent Confidence Intervals

c) Robustness Checks

Robustness checks are essential in statistics and causal inference since they assess the sensitivity of results to changes in model specifications, control variables, and assumptions.141 By testing the validity and generalizability of findings across different scenarios, robustness checks help ensure the reliability of statistical models.142 They address potential biases, minimize the risk of spurious results, and contribute to transparency and reproducibility in research.143 In effect, robustness checks play a crucial role in enhancing the credibility and robustness of statistical conclusions by examining the stability of results under various conditions and specifications.144 Because the results described in the Findings subsection remain robust to all of the alternative specifications, the following text describes the key tests below.

Reverse Causality. The existence of a positive correlation between BLAs and SAIM does not necessarily mean that the former causes the latter. It may be just as likely that improvements in SAIM cause countries to form BLAs. Indeed, in a study finding a link between BLAs and increased migration to host countries, Chilton and Posner noted that further evidence would be necessary to rule out the possibility that “rising migration causes countries to enter into BLAs” rather than the other way around.145 This robustness check thus consisted of rerunning the analysis described in the Findings subsection using a cross-lagged panel model, which “offers protection against bias arising from reverse causality under a wide range of conditions[.]”146

Control Group. A major question in any causal inference framework is “whether never-treated units can be regarded as a suitable control group.”147 Table 4 shows that the Treatment and Control group countries have parallel (i.e. statistically indistinguishable) trends in SAIM, meeting the key assumption of the event study approach used here.148 This suggests some underlying similarities between the groups of countries before the Treatment group formed BLAs. But to address the possibility that Treatment group countries systematically differ from those in the Control group—in ways that violate the parallel trends assumption—and that these differences may have been amplified once Treatment group countries entered BLAs,149 this check implemented a matching method called Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM).150 The idea behind this approach is to reduce bias and improve balance in the observable variables between treatment and control groups.151 CEM works by categorizing or “coarsening” continuous variables into discrete blocks or intervals, and then matching units with the same coarsened values exactly.152 The goal is to achieve balance in the distribution of covariates, making the treatment and control groups more comparable.153 This check thus entailed creating a matched sample with groups of countries that differ in whether they ever entered a BLA with the Philippines but have identical values on all of the Control Variables. The multivariate L1 distance, an index of the degree of global imbalance across the relevant variables,154 was 0.521 before matching and effectively zero after matching. The final step of the check consisted of re-estimating models using this matched sample.

Influential Observations. Though the Treatment group contains 24 different countries, these countries comprise a relatively small share of the total sample of countries. Moreover, certain countries, such as South Korea and Canada,155 have entered into many BLAs with the Philippines during the period of interest. It is possible that a few of these countries could be outliers in their responses to forming BLAs, exercising an outsized influence on the estimates produced in the previous subsection. To check that these results were not driven by a small number of outlier or high-leverage countries with BLAs, this approach entailed re-estimating models using quantile regression.156 To address the same concern about influential observations, this model used methods for identifying multivariate outliers157 and re-estimated models (1) with an indicator for whether a given observation had been marked as an outlier, and (2) reweighing the influence of a given observation inversely to its estimated distance from other observations (in effect this statistically penalizes an observation to the degree it is an outlier). Under these and a series of other alternate specifications, the statistical significance, size, and direction of the results as presented in the Findings subsection did not change substantially.

3. Discussion of analysis

The foregoing analysis allows this Comment to speak and make contributions to three ongoing conversations in legal scholarship. These conversations are on international law and social science, BLAs and their effects, and the utility of international agreements. The subsections below touch on each of these different areas and the relevant contributions that this Comment makes to each.

a)The Social Science Approach to International Law

As mentioned earlier, Daniel Abebe and colleagues recently issued a call for more social science research in the study of international law.158 Part of this call likely stems from the problem that Jack Goldsmith and Eric Posner identified with international legal scholarship, namely, that such “scholarship has fallen behind other areas of legal scholarship by at least thirty years” because of its slow uptake of the methodological and empirical orientation of social sciences.159 The social science approach to international law not only provides insightful contributions to ongoing debates, but it also allows for scholarship to ask an entirely new category of question. Abebe and his coauthors note as much in their discussion of the distinction between “internal” and “external” questions in international law.160 The “internal” approach “is at its core a doctrinal exercise” while the “external” approach “examines the law from outside, seeking to explain how it came to be or what its consequences might be in the real world.”161 The social science approach to international law is uniquely suited for the latter category of question.162 This allows international legal scholarship to move from what Gregory Shaffer and Tom Ginsburg have called “stale” questions such as “whether international law matters” to pivotal questions about “the conditions under which international law is formed and [its] effects.”163

This Comment’s focus on the effects of BLAs embodies the so-called “external” approach to international legal scholarship. Beyond just asking a certain type of question, this approach entails crafting a concrete hypothesis open to empirical evaluation, selecting a research design and relevant data to gauge the hypothesis’s validity, and presenting findings while recognizing the underlying assumptions and acknowledging the associated uncertainty.164 This Comment’s approach thus allows it to expand on a burgeoning body of methodologically-similar international law research that explicitly acknowledges this orientation.165 The analysis from the foregoing sections can, accordingly, help to develop what Shaffer and Ginsburg have called “conditional” international law theory, which builds knowledge about “the conditions under which international law … has effects in different contexts, aiming to explain variation.”166 In this vein, this Comment builds a novel perspective on BLAs and their consequences for various stakeholders using social science methodology.

Moreover, while scholars working within the social science approach of international law have begun to use empirical methods of text analysis,167 use of sentiment analysis techniques to characterize the content of speech acts, in particular, remains rare. This Comment thus shows the methodological utility of sentiment analysis for international law research. Considering the proliferation of natural-occurring text-based data that exist today—such as the UNGA debate database used here—considerable upside exists for researchers to continue applying sentiment analysis in ways that advance scholarly understanding on the causes and effects of international law.

b) BLAs and Their Effects

Now, to get into the substance of the relationship between theory and the analysis, the figures and regression models from the previous subsection unveil a non-random pattern in sentiment changes subsequent to the formation of a BLA with the Philippines. This pattern is characterized by an initial surge in sentiment followed by a gradual return to pre-BLA levels. These findings bear statistical significance and persist when controlling for various factors, including year and country fixed effects, underscoring the potential influence of BLAs on sentiment about international migration. These observations imply that BLAs may play a role in shaping how countries perceive and discuss international migration.

The findings offer insights into the complex and potentially contradicting effects of international law on the sentiment of political elites and shed light on the nuanced relationship between legal agreements and political elites’ discourse of migration. These insights include a few main points. First, context matters. Observation of an initial positive shift in sentiment following the formation of BLAs, followed by a gradual return to baseline levels, underscores the importance of considering the specific historical and geographic context in which international law operates. Some prior research has suggested that pro-migrant laws generally encourage pro-migrant sentiment,168 while other research has found international laws aimed at protecting migrant rights can trigger backlash.169 The findings here emphasize that the impact can vary over time and in different settings, suggesting that the expressive effects of international law may be context dependent. These findings highlight the need to consider not only the immediate effects but also the longer-term dynamics that may result from international legal agreements. Considering different time horizons may allow for existing discrepancies in research to be reconciled.

Second, results suggest BLAs may have an “independent” effect on political elites’ sentiment vis-à-vis international migration. That is, these results remain robust to the inclusion of control variables. Earlier, the paper mentioned the possibility that changes in sentiment vis-à-vis international migration might be the outcome of other consequences of BLAs. The example provided was that BLAs could cause economic growth in a country, which would, in turn, prompt politicians to speak more favorably about international migration after they see evidence of some benefit connected to BLAs. The fact the models here adjust for the effect of GDP, accordingly, suggests that BLAs could have some effect on sentiment vis-à-vis international migration independent of economic growth (or any of the other control variables for that matter).

This is consistent with the hypothesis that BLAs have an expressive effect. While international scholarship has already noted the expressive potential of international agreements, such scholarship has largely focused on human rights agreements.170 BLAs are qualitatively distinct from agreements. Unlike human rights agreements,171 explicit “commitments to norms or values” are not consistently built into BLAs.172 Indeed, BLAs do not even consistently include protections for migrant workers’ rights.173

Moreover, from an ex ante perspective, it is not immediately obvious that BLAs ought to have an expressive effect that is decidedly pro international migration. There are considerations that point both ways. On the one hand, international organizations have argued that BLAs can confer benefits on participating countries and individuals covered under the agreements. The World Bank, for example, has taken the position that such agreements can facilitate the temporary relocation of in-demand labor and spur economic growth in both the sending and receiving countries.174 The ILO has similarly stated that, when based on international labor standards, BLAs can encourage sound governance over migration, ensure migrants’ human and labor rights, and promote developmental benefits of migration.175 The United Nations Network on Migration has likewise endorsed specific guidelines for successful BLAs and noted the possibilities for enhancing economic well-being and rights.176 Considering these potential benefits alongside impending labor shortages in upper-income countries due to demographic changes, 177 it seems reasonable to assume that BLAs would prompt leaders to use discourse that would embrace international migrants.

But, on the other hand, any cross-border migration can lead to “tensions . . . in global politics.”178 Around the world, “backlash against the open-border paradigm of economic globalization has driven certain domestic worker lobbies to oppose the recruitment of migrant workers.”179 Indeed, in certain sectors, it is common for employers to engage in labor arbitrage strategies whereby “wages are . . . ‘artificially’ kept in check through the continuous, organized influx of migrant workers.”180 And, while BLAs may purport an intention to “manifest a commitment to protecting migrant workers’ rights,” they do not often “include an effective enforcement mechanism” that guarantees these rights are received.181 In other words, BLAs may very well be used to undercut the strength of organized labor domestically. So, politicians vying for the support of such laborers may see it necessary to avoid discussing international migration in a positive light. This could mean that the discourse around BLAs could be negative or that the negative responses to BLAs could counter the positive responses and lead to no change in sentiment on average.

The fact that this Comment identifies effects that are consistent with a positive consequence of BLAs is important as it adjudicates between the multiple plausible outcomes that one might expect given what prior scholarship’s suggestions. It is likely that under some conditions heads of state may speak of international migration in a negative light following the formation of a BLA with the Philippines or other countries. But, on average, the formation of BLAs with the Philippines appears to have a positive, albeit short-term effect on discourse about international migration. This Comment thus helps to adjudicate among three plausible outcomes of BLAs and establishes that, at least under the conditions identified in this study, one is more likely.

c) On the Utility of International Agreements

Because the findings of this case study document an unintended effect of BLAs, they can speak to broader conversations about international agreements. A certain line of scholarship has theorized that many treaties are unlikely to have any detectable effect.182 This viewpoint arises, in part, due to the tendency of countries to engage in treaty negotiations with limited commitments, consequently leading to many international agreements having minimal impact on the behavior of the parties for which they were originally intended to exert influence.183

In the case of BLAs, accordingly, the minimal change in intended outcomes may suggest that participating parties have a limited commitment to the agreements. Indeed, multiple studies note that BLAs with the Philippines didn’t necessarily increase the flow of migrants.184 But, based on this Comment’s findings, the added expressive effects appear regardless of changes in economic activity or influxes of migrants.

On this point, consider Justice Kennedy’s concurrence in Board of Trustees v. Garrett,185 which dealt the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): “[o]ne of the undoubted achievements of statutes designed to assist those with impairments is that citizens have an incentive, flowing from a legal duty, to develop a better understanding, a more decent perspective, for accepting persons with impairments or disabilities into the larger society.”186 Justice Kennedy further maintained that “[t]he law works this way because the law can be a teacher.”187

Justice Kennedy’s argument that the law can serve as a “teacher” proves insightful here. Like the ADA, international agreements, even if not acted on, may create legal duties and incentives that can reshape the perspectives of the participating societies. Consistent with this notion, this Comment suggests that, despite a lack of consistent material effects, some international agreements may still have some non-negligible consequences for the social construction of groups governed and affected by the agreements. On hot-button global issues—such as international migration—knowing that such laws can lower the temperature of escalatory and extreme rhetoric and positions seems important, especially given the ability of the discourse of political elites to shape the attitudes and behavior of the public.188 Even if there is no immediate added material value to international agreements, there may be something worthwhile about engaging in rituals that memorialize goodwill and encourage future cooperation, potentially leading to the creation of future legal instruments with more tangible consequences.

Admittedly, this Comment does not rebut the presumption that international agreements often do not accomplish what they set out to. Comparing the intended consequences of a law against its actual consequences is an important form of analysis. And to the extent that many agreements are ineffective in this regard, this type of comparison can provide an important critique. But the findings of this Comment suggest that a more comprehensive assessment of international agreements may be necessary before dismissing their influence outright. Inasmuch as international agreements may alter symbolic actions in high-stakes, high-profile settings such as the UNGA, it suggests that some of them have succeeded in “teaching” participants and instilling new perspectives. Though beyond the scope of this analysis, the discursive shift associated with some international agreements may also have important downstream consequences.

V. Conclusion

Over the last century, countries have signed hundreds of BLAs to govern the international movement of migrant workers.189 The discussion surrounding BLAs highlights their dual potential—serving as tools to address global workforce imbalances and promote economic development while also exposing the tensions and resistance that often accompany cross-border migration. Despite the aspirational goals of these agreements, their efficacy in achieving their intentions remains unclear.

To understand how BLAs interact with and influence discourse about global migration, this Comment applies social science in international law and expressive effects of law perspectives. In particular, this Comment delves into the sentiments expressed by political elites in UNGA debates as a lens through which to understand the impact of BLAs on sentiment. The findings from a case study analyzing BLAs with the Philippines unveil the expressive impact of these agreements. They reveal that BLAs indeed appear to have some expressive effects. Intriguingly, while BLAs initially drive a positive shift in sentiment, this effect diminishes over time, eventually reverting to baseline levels. These observations underscore the interplay between international law and attitudes regarding migration and suggest the possibility of context-dependent expressive effects.

In a broader context, this Comment contributes to ongoing discussions about the importance of international agreements. It suggests that even when these agreements do not yield immediate tangible outcomes, they can still play a role in shaping the perception and discourse surrounding affected groups. This suggests there still may be some inherent value to international agreements, insofar as they encourage cooperation and goodwill towards marginalized groups, particularly on contentious global issues such as international migration.

- 1Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf, Statement for U.N. General Assembly General Debate, 67th Sess. (Sept. 25, 2012), https://perma.cc/ST6X-SV2U.

- 2Id.

- 3Doris Leuthard, Statement for U.N. General Assembly General Debate, 72nd Sess. (Sept. 19, 2017), https://perma.cc/GDY5-KR47.

- 4Id.

- 5Id.

- 6Id.

- 7See, e.g., Lionel Marquis, The Psychology of Quick and Slow Answers: Issue Importance in the 2011 Swiss Parliamentary Elections, 20 Swiss Pol. Sci. Rev. 697, 709 (2014) (classifying Leuthard’s Christian Democratic People’s Party of Switzerland (CVP) as “right-of-center”).

- 8Gregor Aisch et al., How Far is Europe Swinging to the Right?, N.Y. Times (May 22, 2016), https://perma.cc/X74Q-AEYX.

- 9Pazit Ben-Nun Bloom, Gizem Arikan & Gallya Lahav, The Effect of Perceived Cultural and Material Threats on Ethnic Preferences in Immigration Attitudes, 38 Ethnic & Racial Stud. 1760, 1760 (2015).

- 10Arturo Castellanos-Canales, Bilateral Labor Agreements: A Beneficial Tool to Expand Pathways to Lawful Work, Nat’l Immigration F. (July 20, 2022), https://perma.cc/6S8H-L5TL.

- 11Yuval Livnat & Hila Shamir, Gaining Control? Bilateral Labor Agreements and the Shared Interest of Sending and Receiving Countries to Control Migrant Workers and the Illicit Migration Industry, 23 Theoretical Inq. L. 65, 65 (2022).

- 12See infra Table 1.

- 13See, e.g., Livnat & Shamir, supra note 11.

- 14University of Chicago Law School, Bilateral Labor Agreements Dataset, https://perma.cc/8PT9-K6PD (last visited Oct. 16, 2024) (showing over 400 BLAs signed in 2019—the most recent year for which complete data appear); Adam Chilton et al., Bilateral Labor Agreements Dataset, Harv. Dataverse, V1 (Aug. 30, 2017), https://perma.cc/QV6Q-RWEP5HDP-46MM.

- 15Ian Peacock & Emily Ryo, A Study of Pandemic and Stigma Effects in Removal Proceedings, 19 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 560, 563 (2022) (reviewing studies showing how anti-Chinese sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to increased discrimination).

- 16René Flores, Can Elites Shape Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants?: Evidence from the 2016 US Presidential Election, 94 Soc. Forces 1649, 1649 (2018); Peacock & Ryo, supra note 15.

- 17Daniel Abebe, Adam Chilton & Tom Ginsburg, The Social Science Approach to International Law, 22 Chi. J. Int’l L. 1, 5 (2021).

- 18See, e.g., Gregory Shaffer & Tom Ginsburg, The Empirical Turn in International Legal Scholarship, 106 Am. J. Int'l L. 1 (2012); Jack Goldsmith & Eric A. Posner, Response, The New International Law Scholarship, 34 Ga. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 463 (2006).

- 19Richard H. McAdams, An Attitudinal Theory of Expressive Law, 79 Or. L. Rev. 339, 340 (2000).

- 20See, e.g., Jack L. Goldsmith & Eric A. Posner, The Limits of International Law (2005) (arguing that international agreements and international law are unlikely to independently affect state actions); see also Abebe et al., supra note 17, at 13 (summarizing Goldsmith & Posner by stating that the authors “argue[] that international law should be better understood as endogenous to state preferences instead of as an exogenous constraint on state behavior.”); Paul S. Berman, Seeing Beyond the Limits of International Law, 84 Tex. L. Rev. 1266 (2006) (summarizing Goldsmith & Posner by characterizing their argument as “an attempt to demonstrate that international law has no independent valence whatsoever”).

- 21Again, this is especially important because the rhetoric of political elites can shape public opinions and behavior. See Flores, supra note 16.

- 22Adam Chilton & Bartosz Woda, The Expanding Universe of Bilateral Labor Agreements, 23 Theoretical Inquiries L. 1, 2 (July 2022).

- 23Brianna O’Steen, Bilateral Labor Agreements and the Migration of Filipinos: An Instrumental Variable Approach, 12 IZA J. Dev. & Migration 1, 2 (2021).

- 24Id.

- 25Id.

- 26Id.

- 27Id.

- 28Id.

- 29O’Steen, supra note 23, at 12.

- 30Id.

- 31Id.

- 32Id.

- 33Id.

- 34Wolf Böhning, A Brief Account of the ILO and Policies on International Migration 4 (2012) (draft paper on file with the International Labor Organization).