Studying Race in International Law Scholarship Using a Social Science Approach

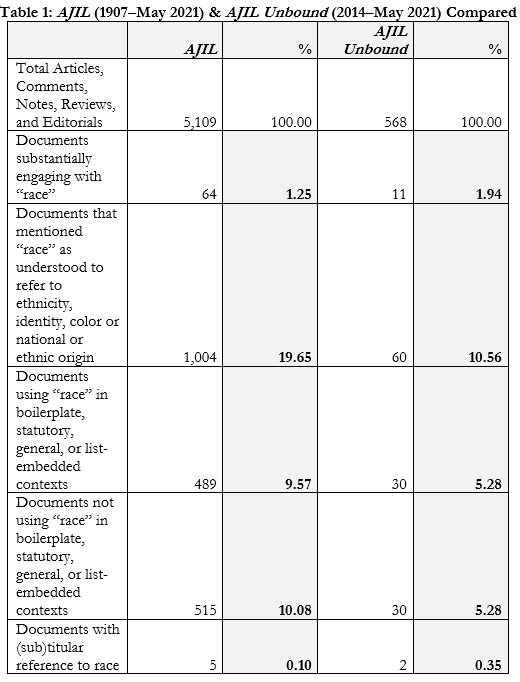

This Essay takes up Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg’s invitation to use a social science approach to establish or ascertain some facts about international law scholarship in the United States. The specific research question that this Essay seeks to answer is to what extent scholarship has addressed international law’s historical and continuing complicity in producing racial inequality and hierarchy, including slavery, as well as the subjugation and domination of the peoples of the First Nations. To answer this question, this Essay uses the content published in the American Journal of International Law (AJIL) from when it was first published in 1907 to May 2021. It also uses the content published in its sister publication AJIL Unbound from when it was first published in 2014 to May 2021. The most significant finding of this Essay is that only 64, or 1.25%, of 5,109 AJIL documents substantially engaged with race in the body of their texts. In AJIL Unbound, only 11, or 1.94%, of the 568 documents substantially engaged with race in the bodies of their text.

To account for the extremely low number of documents substantially engaging with race in the pages of the leading international law journal, I advance four hypotheses. First, that this absence is a reflection of the conscious exclusion of African Americans in the American Society of International Law in the first six decades of its existence, as the 2020 Richardson Report found. Second, it is the result of the stringent scrutiny race scholarship in international law has faced in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. Third, that the big or defining debates about international law in the United States have focused on issues other than race, and fourth that color-blindness has been the default view of American international law scholarship as represented in the journal.

Ultimately, the point of this Essay is threefold. First, to show that the social science approach that Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg advance can be useful to answer questions that critical scholars like myself are interested in. Second, that when this social science approach is applied to answer questions like the one pursued in this Essay the distinction between the neutrality of the scientific methodology of this social scientific approach, on the one hand, and the normativity of critical approaches that Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg argue characterizes other approaches, on the other, falls apart. Third, this Essay shows that there is still ample scope for more international law scholarship on race that needs to be taken up not only by scholars of color but by all scholars of international law.

I. Introduction

This Essay sets out to determine to what extent scholarship has addressed international law’s historical and continuing complicity in producing racial inequality and hierarchy, including slavery, as well as the subjugation and domination of the peoples of the First Nations. To answer this question, this Essay uses the content published in the American Journal of International Law (AJIL) from its inception in 1907 through 2021, as well as in AJIL Unbound, its online companion, from its first publication in 2014 through 2021.1 I want to make it clear from the onset that my research question is very narrow. I am interested only in establishing whether scholarship that probes the racist underpinnings of international law, as well as the racial hierarchies upon which international law was constructed, has been published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. In doing so, I am excluding from the scope of this paper the ways in which AJIL was itself a site of racialized discourses such as “civilization” and “humanity.”2 Other scholars have begun to examine AJIL’s complicity in the construction and perpetuation of racially exclusionary discourses such as “civilization” and “humanity.” Benjamin Allen Coates reminds us, very early in its founding, AJIL justified spreading U.S. hegemony not merely through the notion of “civilizing savages,” but rather that of civilizing “the world as a whole”3 in the progressive era commitment and faith in the progress of civilization “whether conceived of in terms of Christianity, natural or social science, governance, or commerce.”4 In fact, international law was critical to justifying the U.S.’s annexation of the Philippines and Puerto Rico, the establishment of a protectorate over Cuba, and the takeover of Panama to build a canal.5 It is against this backdrop of the end of the Spanish-American War and the emerging empire acquired by the United States that AJIL came into existence.6 Benjamin Allen Coates therefore argues that AJIL Board members of the early twentieth century were “not isolated idealists spouting naive bromides from the sidelines. Well-connected, well-respected, and well-compensated, they formed an integral part of the foreign policy establishment that built and policed an expanding empire.”7

To emphasize, I am interested in whether AJIL and AJIL Unbound have published scholarship that critically engages with the racist and imperial structures of international law that justified slavery, colonialism, and empire. I am also interested in examining AJIL’s role in constructing and perpetuating racially exclusionary discourses.8 To use Mohsen al Attar’s extensive comments on an earlier version of this Essay, I am interested in establishing whether the American international legal academy has been complicit “in collective acts of epistemic injustice.”9 In particular, has AJIL and AJIL Unbound silenced and/or excluded critical approaches to international law, especially those influenced by Critical Race Theory or Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), in the pages of the leading international law journal in the United States?10

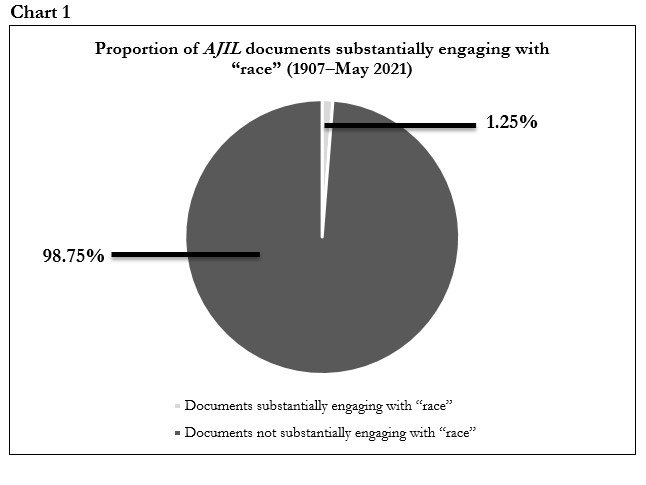

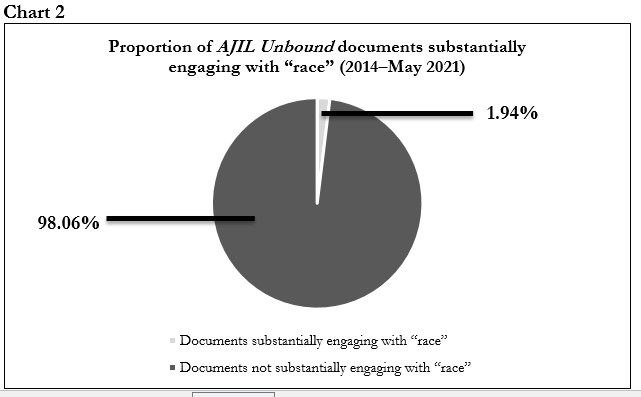

The results of my empirical analysis showed that only 64, or 1.25%, of 5,109 AJIL documents substantially engaged with race in the body of their texts. In AJIL Unbound, only 11, or 1.94%, of the 568 documents substantially engaged with race in the bodies of their text.

To explain the extremely little content published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound over 100 years addressing international law’s historical and continuing complicity in producing racial inequality and hierarchy, including slavery, as well as the subjugation and domination of the peoples of the First Nations, this Essay advances four hypotheses. First, this absence is a reflection of the conscious exclusion of African Americans in the American Society of International Law in the first six decades of its existence, as the 2020 Richardson Report found.11 Second, this gap is the result of the stringent scrutiny international law scholarship addressing international law’s historical and continuing complicity in producing racial inequality and hierarchy has faced in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. Third, the big or defining debates about international law in the United States have focused on issues other than race. And fourth, color-blindness has been the default view of American international law scholarship as represented in the journal.

This Essay proceeds as follows. In Section II, I outline the methodology I followed in gathering the data. The third section of the Essay is my ongoing effort to account for the paucity of scholarship centering race in AJIL and AJIL Unbound.

II. AJIL Content-Analysis Methodology and Results

In order to determine an answer to my question—whether scholarship that probes the racist and imperial underpinnings of international law, as well as the racial hierarchies upon which international law was constructed, has been published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound—my methodology was as follows. I began by establishing whether there was such content in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. To do so, I searched the content of AJIL and AJIL Unbound using HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.12 Although AJIL and AJIL Unbound documents can be accessed from the Cambridge Core site,13 HeinOnline served as a much better tool for this study for at least two reasons. First, unlike Cambridge Core, HeinOnline makes it possible to simultaneously search AJIL and AJIL Unbound. Second, since Cambridge Core represents the main portal for subscriptions and sales of these two publications, using a third-party content site seemed to me more likely to provide an objective count of the content.

To determine whether the content published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound has probed the racist and imperial underpinnings of international law, I undertook the following steps. First, I conducted an Advanced Search in the HeinOnline Law Journal Library using the search string “rac* OR anti-racis* OR antiracis*” and limiting my results to documents in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. This search was designed to retrieve all documents in AJIL and AJIL Unbound that contained any forms of the word “race,” or any of the words “antiracist,” “antiracism,” “anti-racist,” or “anti-racism.”14 I then restricted these search results to the following AJIL and AJIL Unbound section types: Articles, Comments, Notes, Reviews, and Editorials.15 AJIL content that is purely informational, such as Tables of Contents and Legislation, was omitted.16 Thus, the relevant content for my inquiry numbered 1,535 documents in AJIL and 121 in AJIL Unbound, and the total number of documents for the study sample was 1,656.

Next, I examined each of these 1,656 documents individually to determine which ones substantially probed the racist and imperial underpinnings of international law, as well as the racial hierarchies upon which international law was constructed.17 By substantial engagement with race, I am referring to articles that critically examine race (rather than say, states) as a unit of analysis to account for the role racial hierarchy and domination have played and plays in shaping and organizing ideas and institutions of global order including slavery, colonialism, and empire.

To comprehensively assess which of the documents engaged in a substantial analysis of the racist and imperial underpinnings of international law, I also identified documents that (a) mentioned “race” as understood to refer to ethnicity, identity, color or national or ethnic origin; (b) referred to “race” in a boilerplate/statutory/general language form or merely in a list, i.e., these documents used “race” without referring to race, color, or national or ethnic origin; (c) used “race” in a quotation, citation, or footnote; (d) used “race” sporadically or in a one-off manner, i.e., “race” was mentioned only very occasionally, and it was not the primary focus of analysis; and (e) included “race” in the titles or subtitles of the documents.

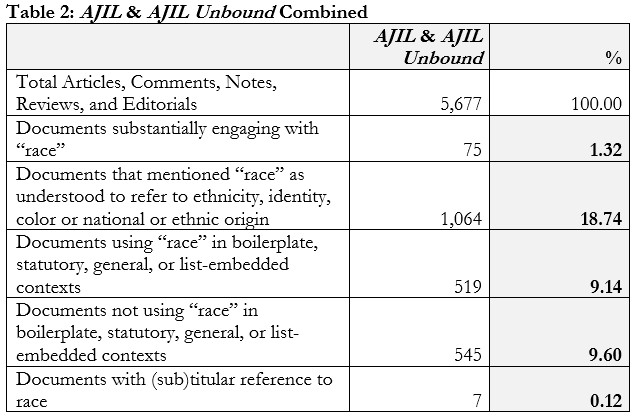

To continue the analysis, I determined the total number of AJIL and AJIL Unbound documents in HeinOnline by conducting an Advanced Search in the Law Journal Library using “*” as the search term and restricting the search to AJIL and AJIL Unbound. I then limited the search results to the same section types included in the relevant sample set as described above, which yielded a total of 5,677 documents. For AJIL, the search produced a total of 5,109 documents. For AJIL Unbound, there was a total of 568 documents.18 With this data in hand, as well as the results of my earlier AJIL and AJIL Unbound content analysis, I was able to address my research question head on.

The data unequivocally shows that AJIL and AJIL Unbound have not frequently engaged with race. This is clearly illustrated by the finding that only 64, or 1.25%, of 5,109 AJIL documents substantially engaged with race in the body of their texts. Furthermore, of the 5,109 total documents in AJIL, 1,004, or 19.65%, incorporated the word “race.” Of those 1,004 documents, 489 of them, or 9.57% of all 5,109 documents, used “race” in a boilerplate, statutory, general, or list-embedded context. Moreover, 515, or 10.08%, of the 5,109 documents did not use “race” in a boilerplate, statutory, general, or list-embedded context. Finally, only 5, or 0.10%, of the 5,109 documents had “race” in their title.

Similarly, in AJIL Unbound, only 11, or 1.94%, of the 568 documents substantially engaged with race in the bodies of their text. Moreover, of the 568 documents published in AJIL Unbound, 60, or 10.56%, incorporated the word “race.” Of those 60 documents, 30 of them, or 5.28% of all 568 documents, used “race” in a boilerplate, statutory, general, or list-embedded context. Finally, only 2, or 0.35%, of the 568 documents had “race” in their title.

These results are presented in more detail in the following data tables (Tables 1, 2, and 3) and related charts (Charts 1 and 2). Appendix 1 lists all the AJIL documents that mentioned “race” in the bodies of their text, and Appendix 2 contains a full list of AJIL Unbound documents that mentioned “race” in their texts. In Appendix 3, Table 5 and Chart 3 analyze the documents listed in Appendices 1 and 2. Appendices are published separately on Chicago Unbound.

Table 3: List of AJIL documents substantially engaging with “race” (1907–May 2021)

|

Title |

Citation |

Author(s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Protection of Minorities by the League of Nations |

17 Am. J. Int’l L. 641 (1923) |

Rosting, Helmer |

|

2 |

Some Legal Aspects of the Japanese Question |

17 Am. J. Int’l L. 31 (1923) |

Buell, Raymond Leslie |

|

3 |

The End of Dominion Status |

38 Am. J. Int’l L. 34 (1944) |

Scott, F.R. |

|

4 |

Current Views of the Soviet Union of the International Organization of Security, Economic Cooperation and International Law: A Summary |

39 Am. J. Int’l L. 450 (1945) |

Prince, Charles |

|

5 |

Book Review (reviewing Carey McWilliams, Prejudice: Japanese-Americans, Symbol of Racial Intolerance (1994)) |

39 Am. J. Int’l L. 634 (1945) |

Das, Taraknath |

|

6 |

Denazification Law and Procedure |

41 Am. J. Int’l L. 807 (1947) |

Plischke, Elmer |

|

7 |

The United Nations Conference on Freedom of Information and the Movement against International Propaganda |

43 Am. J. Int’l L. 73 (1949) |

Whitton, John B. |

|

8 |

An “Act for the Protection of Peace” in Bulgaria (current notes) |

a) 45 Am. J. Int’l L. 353 (1951); b) id. at 357 |

Nicoloff, Antoni M |

|

9 |

National Courts and Human Rights—The Fujii Case |

45 Am. J. Int’l L. 62 (1951) |

Wright, Quincy |

|

10 |

The Trieste Settlement and Human Rights (notes and comments) |

49 Am. J. Int’l L. 240 (1955) |

Schwelb, Egon |

|

11 |

International Law and Some Recent Developments in the Commonwealth (editorial comments) |

55 Am. J. Int’l L. 440 (1961) |

Wilson, Robert R. |

|

12 |

The United Nations’ Double Standard on Human Rights Complaints (notes and comments) |

60 Am. J. Int’l L. 792 (1966) |

Carey, John |

|

13 |

Civil and Political Rights: The International Measures of Implementation |

62 Am. J. Int’l L. 827 (1968) |

Schwelb, Egon |

|

14 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law: South West Africa (Namibia) |

63 Am. J. Int’l L. 320 (1969) |

Denny, Brewster C. |

|

15 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law: Summary of Developments During 23d Session of the U.N. General Assembly |

63 Am. J. Int’l L. 569 (1969) |

Gibson, Stephen L. ed. |

|

16 |

64th Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law (notes and comments) |

64 Am. J. Int’l L. 623 (1970) |

Finch, Eleanor H. |

|

17 |

The International Court of Justice and the Human Rights Clauses of the Charter |

66 Am. J. Int’l L. 337 (1972) |

Schwelb, Egon |

|

I18 |

The 1974 Diplomatic Conference on Humanitarian Law: Some Observations |

69 Am. J. Int’l L. 77 (1975) |

Forsythe, David P. |

|

19 |

Book Review, (reviewing Edward Weisband, Resignation in Protest: Political and Ethical Choices Between Loyalty to Team and Loyalty to Conscience in American Public Life (1975)) |

71 Am. J. Int’l L. 160 (1977) |

Rusk, Dean |

|

20 |

Constitutive Questions in the Negotiations for Namibian Independence |

78 Am. J. Int’l L. 76 (1984) |

Richardson III, Henry J. |

|

21 |

The Meaning and Reach of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination |

79 Am. J. Int’l L. 283 (1985) |

Meron, Theodor |

|

22 |

Federalism and the International Legal Order: Recent Developments in Australia |

79 Am. J. Int’l L. 622 (1985) |

Byrnes, Andrew & Charlesworth, Hilary |

|

23 |

Current Developments: First Session of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights |

81 Am. J. Int’l L. 747 (1987) |

Alson, Philip & Simma, Bruno |

|

24 |

The Meaning of People in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (notes and comments) |

82 Am. J. Int’l L. 80 (1988) |

Kiwanuka, Richard N. |

|

25 |

Threats of Force |

82 Am. J. Int’l L. 239 (1988) |

Sadurska, Romana |

|

26 |

Agora: Is the ASIL Policy on Divestment in Violation of International Law? Further Observations |

82 Am. J. Int’l L. 311 (1988) |

Barrie, George N. & Szasz, Paul C. |

|

27 |

International Law in the Third Reich |

84 Am. J. Int’l L. 661 (1990 ) |

Vagts, Detlev F. |

|

28 |

Feminist Approaches to International Law |

85 Am. J. Int’l L. 613 (1991) |

Charlesworth, Hilary, Chinkin, Christine & Wright, Shelley |

|

29 |

The Emerging Right to Democratic Governance |

86 Am. J. Int’l L. 46 (1992) |

Franck, Thomas M. |

|

30 |

Book Review (reviewing Patrick Thornberry, International Law and the Rights of Minorities (1993)) |

87 Am. J. Int’l L. 680 (1993) |

Hannum, Hurst |

|

31 |

The Gulf Crisis and African-American Interests under International Law |

87 Am. J. Int’l L. 42 (1993) |

Richardson III, Henry J. |

|

32 |

Clan and Superclan: Loyalty, Identity and Community in Law and Practice |

90 Am. J. Int’l L. 359 (1996) |

Franck, Thomas M. |

|

33 |

Indigenous Peoples in International Law: A Constructivist Approach to the Asian Controversy |

92 Am. J. Int’l L. 414 (1998) |

Kingsbury, Benedict |

|

34 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law (General International and U.S. Foreign Relations Law): Interpretation of U.S. Constitution by Reference to International Law |

97 Am. J. Int’l L. 683 (2003) |

Murphy, Sean D. ed. |

|

35 |

Book Review (reviewing Karen Knop, Diversity and Self-Determination in International Law (2002)) |

98 Am. J. Int’l L. 229 (2004) |

Fox, Gregory H. |

|

36 |

Normative Hierarchy in International Law |

100 Am. J. Int’l L. 291 (2006) |

Shelton, Dinah |

|

37 |

Book Review (reviewing Ian Clark, International Legitimacy and World Society (2007)) |

102 Am. J. Int’l L. 926 (2008) |

Davis, Benjamin G. |

|

38 |

Book Review (reviewing Peter J. Spiro, Beyond Citizenship: American Citizenship After Globalization (2008)) |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 180 (2009) |

Rodríguez, Christina M. |

|

39 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law (International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law): United States Boycotts Durban Review Conference, Will Seek Election to Human Rights Council |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 355 (2009) |

Crook, John R. |

|

40 |

The Pillar of Glass: Human Rights in the Development Operations of the United Nations |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 446 (2009) |

Darrow, Mac & Arbour, Louise |

|

41 |

Current Developments: The 2008 Judicial Activity of the International Court of Justice |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 527 (2009) |

Mathias, D. Stephen |

|

42 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law (International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law): UN Human Rights Officials Berate U.S. Human Rights Policies and Practices |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 594 (2009) |

Crook, John R. |

|

43 |

Book Review (reviewing Daniel Moeckli, Human Rights and Non-discrimination in the ‘War on Terror’ (2008)) |

103 Am. J. Int’l L. 635 (2009) |

Shah, Sikander A. |

|

44 |

Book Review (reviewing Thomas Buergenthal, A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy (2010)) |

104 Am. J. Int’l L. 307 (2010) |

Damrosch, Lori Fisler |

|

45 |

Book Review (reviewing Henry J. Richardson III, The Origins of African-American Interests in International Law (2008)) |

104 Am. J. Int’l L. 313 (2010) |

Gordon, Ruth |

|

46 |

Protection of Indigenous Peoples on the African Continent: Concepts, Position Seeking, and the Interaction of Legal Systems |

104 Am. J. Int’l L. 29 (2010) |

van Genugten, Willem |

|

47 |

Book Review (reviewing Jeremy I. Levitt, Africa: Mapping New Boundaries in International Law (2008)) |

104 Am. J. Int’l L. 532 (2010) |

Mutua, Makau |

|

48 |

A New International Law of Citizenship |

105 Am. J. Int’l L. 694 (2011) |

Spiro, Peter J. |

|

49 |

Application of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Georgia v. Russian Federation) |

105 Am. J. Int’l L. 747 (2011) |

Szewczyk, Bart M. J. |

|

50 |

Genocide: A Normative Account |

105 Am. J. Int’l L. 852 (2011) |

Greenawalt, Alexander K.A. |

|

51 |

Current Developments: The 2011 Judicial Activity of the International Court of Justice |

106 Am. J. Int’l L. 586 (2012) |

Cogan, Jacob Katz |

|

52 |

Book Review (reviewing Sundhya Pahuja, Decolonizing International Law: Development, Economic Growth and the Politics of Universality (2011)) |

107 Am. J. Int’l L. 494 (2013) |

Gathii, James Thuo |

|

53 |

Book Review (reviewing Ryan Goodman & Derek Jinks, Socializing States: Promoting Human Rights through International Law (2013)) |

108 Am. J. Int’l L. 576 (2014) |

Sloss, David |

|

54 |

Exploitation Creep and the Unmaking of Human Trafficking Law |

108 Am. J. Int’l L. 609 (2014) |

Chuang, Janie A. |

|

55 |

The Creation of Tribunals |

110 Am. J. Int’l L. 173 (2016) |

Matheson, Michael J. & Scheffer, David |

|

56 |

The 2017 Judicial Activity of the International Court of Justice (notes and comments) |

112 Am. J. Int’l L. 254 (2018) |

Gray, Christine |

|

57 |

Book Review (reviewing Oona A. Hathaway & Scott J. Shapiro, The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World (2017)) |

112 Am. J. Int’l L. 330 (2018) |

Bradley, Anna Spain |

|

58 |

Human Rights in War: On the Entangled Foundations of the 1949 Geneva Conventions |

112 Am. J. Int’l L. 553 (2018) |

van Dijk, Boyd |

|

59 |

Book Review (reviewing David L. Sloss, The Death of Treaty Supremacy: An Invisible Constitutional Change (2016)) |

112 Am. J. Int’l L. 779 (2018) |

Stewart, David P. |

|

60 |

Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law (General International and U.S. Foreign Relations Law): Department of Justice Declines to Defend the Constitutionality of a Statute Criminalizing Female Genital Mutilation |

114 Am. J. Int’l L. 289 (2020) |

Galbraith, Jean |

|

61 |

The Proof Is in the Process: Self-Reporting under International Human Rights Treaties |

114 Am. J. Int’l L. 1 (2020) |

Creamer, Cosette D. & Simmons, Beth A. |

|

62 |

The Pandemic Paradox in International Law |

114 Am. J. Int’l L. 598 (2020) |

Danchin, Peter G., Farrall, Jeremy, Rana, Shruti & Saunders, Imogen |

|

63 |

The Limits of Human Rights Limits (reviewing Hurst Hannum, Rescuing Human Rights: A Radically Moderate Approach (2019)) |

115 Am. J. Int’l L. 154 (2021) |

Richardson III, Henry J. |

|

64 |

Book Review (reviewing Bertrand G. Ramcharan, Modernizing the UN Human Rights System (2019) |

115 Am. J. Int’l L. 171 (2021) |

Chimni, B. S. |

Table 4: List of AJIL Unbound documents substantially engaging with “race” (2014–May 2021)

|

S. No. |

Title |

Citation |

Author(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

A Crossroads in the Fight Against Human Trafficking? Let’s take the Structural Route: A Response to Janie Chuang Symposium: Janie A. Chuang, Exploitation Creep and the Unmaking of Human Trafficking Law |

108 AJIL Unbound 272 (2014-2015) |

Bravo, Karen E. |

|

2 |

Why Fighting Structural Inequalities Requires Institutionalizing Difference: A Response to Nienke Grossman Symposium on Nienke Grossman, Achieving Sex-Representative International Court Benches |

110 AJIL Unbound 92 (2016-2017) |

Torbisco-Casals, Neus |

|

3 |

Human Mobility and the Longue Duree: The Prehistory of Global Migration Law Symposium on Framing Global Migration Law - Part II |

111 AJIL Unbound 136 (2017-2018) |

Bhabha, Jacqueline |

|

4 |

Human Rights and the Future of Being Human Symposium on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at Seventy |

112 AJIL Unbound 324 (2018) |

Huneeus, Alexandra |

|

5 |

Race and Rights in the Digital Age Symposium on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at Seventy |

112 AJIL Unbound 339 (2018) |

Powell, Catherine |

|

6 |

Theorizing Emancipatory Transnational Futures of International Labor Law Symposium on Transnational Futures of International Labor Law |

113 AJIL Unbound 390 (2019) |

Blackett, Adelle |

|

7 |

Towards Global Governance: The Inadequacies of the UN Drug Control Regime Symposium on Drug Decriminalization, Legalization, and International Law |

114 AJIL Unbound 291 (2020) |

Eliason, Antonia & Howse, Robert |

|

8 |

Introduction to the Symposium on COVID-19, Global Mobility and International Law |

114 AJIL Unbound 312 (2020) |

Achiume, E. Tendayi, Gammeltoft-Hansen, Thomas & Spijkerboer, Thomas |

|

9 |

Fortress Europe, Global Migration & the Global Pandemic Symposium on COVID-19, Global Mobility and International Law |

114 AJIL Unbound 342 (2020) |

Reynolds, John |

|

10 |

“To Restore the Soul of America”: How Domestic Anti-Racism Might Fuel Global Anti-Racism Symposium on the Biden Administration and the International Legal Order: Essay |

115 AJIL Unbound 63 (2021) |

Lovelace, H. Timothy Jr. |

|

11 |

Introduction to the Symposium on the Biden Administration and the International Legal Order |

115 AJIL Unbound 40 (2021) |

Shaffer, Gregory & Sloss, David L. |

III. Explaining the Results

What explains the extremely low engagement with race as a theme in AJIL and AJIL Unbound? From AJIL’s founding in 1907 to May 2021, only 1.25% of its documents (64 out of 5,109) substantially engaged with race in the body of their text, and only 0.10% (5 out of 5,109) had race in their titles. Likewise, from AJIL Unbound’s establishment in 2014 to the beginning of 2021, only 1.94% of its documents (11 out of 568) substantially engaged with race in the body of their text, and only 0.35% (2 out of 568) had race in their titles. This is indicative of a silence that requires further exploration.

It is implausible and factually inaccurate to explain this silence as indicative of the irrelevance of race in international law. Bearing in mind that I use race to refer to relations of domination rather than personal prejudice, at least since the sixteenth century when Francisco de Vitoria wrote his treaties, international law has justified slavery, conquest, colonialism, commerce, and other forms of domination over non-European peoples by European peoples. As Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL) and Critical Race Theory (CRT) scholars have shown, international law legitimized colonial conquest along the axes of European/non-European, colonizer/colonized, civilized/uncivilized, and modernity/tradition.19 On this view:

imperial international law was constructed on the basis of White racial superiority—as rational stewards of the territories of non-Europeans—and on the basis of racist myths of indigenous savagery, primitivism, and pathology. Hence, just as slavery dehumanized Blacks as degenerate and outside the boundaries of humanity in the construction of the United States as a White racial state, European/White international law was constructed to relegate non-European peoples who were considered to live outside the bounds of humanity and therefore outside of sovereignty.20

TWAIL scholars argue that notwithstanding international law’s commitments to sovereign equality, human rights, and development, it carries within it the legacy of economic subordination and hierarchy established in prior eras of subjugation, including during slavery and colonial rule.21 Consistent with this rejection of clean historical breaks in histories of international law, race continues to be a salient analytic category in international law. As Antony Anghie argues, understanding the “role of race and culture in the formation of basic international law doctrines such as sovereignty is crucial to an understanding of the singular relationship between sovereignty and the non-European world.”22 In addition, to use the example of Black intellectuals, there is a strong Black internationalist tradition.23 This intellectual tradition, associated in particular with anti-slavery and anti-colonialism, runs from W.E.B. DuBois, who argued the problem of the twentieth century was the color line, to contemporary colleagues like Ruth Gordon, Henry J. Richardson III, and Adrien Katherine Wing, to name a few.24 In addition, in my ongoing research, I continue to uncover other African American international law scholars who have also remained invisible in the casebooks, journal pages, and discussions of international law.25 This includes Yusuf Naim Kly, whose monograph International Law and the Black Minority in the U.S. was published in 1985.26 His edited book A Popular Guide to Minority Rights was published a decade later with the support of the European Human Rights Foundation.27 These and many other examples also discount the view that African American scholars have not or are not producing international law scholarship. To be clear, I do not assume that only African Americans or that all African Americans should produce scholarship about race and international law. To make such a claim would be inaccurate.28

So what accounts for AJIL and AJIL Unbound’s extremely limited publication of scholarship probing the racist underpinnings of international law, as well as the racial hierarchies upon which international law was constructed? Why is it that these two publications have had no tradition of publishing scholarship that traces international law’s historical and continuing complicity in producing racial inequality and hierarchy including slavery, as well as the subjugation and domination of the peoples of the First Nations?

A. Hypothesis One: Conscious Exclusion of African Americans Until Recently

The 2020 Richardson Report adopted by the American Society of International Law, under whose umbrella AJIL is published, concluded that “during the first six decades of the existence and growth of the Society,” the Society “silently [and] effectively exclude[d] domestic persons of color and others, based on their ethnicity, culture, religion or sexual orientation.”29 This factual finding is consistent with evidence in other areas of scholarship where scholars have argued that decisions to restrict minorities by college chancellors and presidents have shaped the current moment in higher education.30

Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg also cite a letter written to the editors of AJIL in 1999 noting that a then recently published agora of the methods of international law did not include any perspectives relating to the concerns of scholars of color.31 In that letter, Henry J. Richardson III wrote about the exclusion as follows:

[I] was sadly disappointed that critical race theory/Latino critical legal theory (CRT/LCT) was omitted totally from that discussion, even to the absence of a single footnote. That omission crucially distorts the symposium by ignoring the emergence in the last two decades of new approaches to international law, based on determinations by people of color that in order to erase embedded systematic discrimination they must become jurisprudential producers and not merely remain jurisprudential consumers.32

Further, it was not until 2014, about 107 years after AJIL was founded, that an African American was first elected to sit on its Board of Editors. It can be inferred from this history of exclusion, what the report calls the silent and effective exclusion of domestic persons of color, that it is not surprising that AJIL has not focused extensively on tracing the relevance of race to international law.33 The history of AJIL until 2014 (when the first African American got elected following changes in AJIL regulations that made this possible) indicates that the emphasis on diversifying the Board focused on dimensions, such as “countries of origin, primary affiliations . . . current geographical locations . . . the participation of women and the involvement of scholars at earlier stages in their careers, as well as through attention to scholarship at the intersection of international law with other disciplines,”34 but not on racial diversity and in particular of domestic racial minorities.

This exclusion of African Americans also likely accounts for the epistemic silencing of articles critical of the racist underpinnings of international law. In 1994, Richardson observed that Black “international lawyers are expected either to enter with the same policy assumptions and theoretical approaches held by white international lawyers, or over a short time to be socialized into the same experience.”35 This exclusion has therefore made it difficult to generate scholarship that probes the Eurocentric and racist foundations of international law.36 With regard to raising issues of race among American international lawyers, Richardson notes: “When a [B]lack lawyer threatens to show other starting points, white-shoe lawyers respond with all of the litigational opposition, bureaucratic undercutting, and subtle destruction that they throw against their worst professional colleagues.”37

This is a critical insight since African Americans and much of the Global South rose up against chattel slavery in the new world and alien, racist colonial rule “not by a critique structured by Western conceptions of freedom but by a total rejection of enslavement and racism as it was experienced.”38

A recent study in the completely different field of psychological research sought to establish how often scholarship on psychology and race was published in top-tier cognitive, developmental, and social psychology journals. It found after examining 26,000 empirical articles published from 1974 to 2018:

First, across the past five decades, psychological publications that highlight race have been rare, and although they have increased in developmental and social psychology, they have remained virtually nonexistent in cognitive psychology. Second, most publications have been edited by White editors, under which there have been significantly fewer publications that highlight race.39

In June 2021, it was disclosed that the leading medical journals in the United States, including the Journal of the American Medical Association, had rarely addressed issues relating to race and racism.40 I cite these studies to highlight the striking parallels between my findings and those in completely different fields where the composition of the editors has been overwhelmingly white and where there have also been few publications relating to race. This absence of articles that explicitly probe whether international law has anything to do with race constitutes a colorblindness that, as I have argued elsewhere, is characteristic of how mainstream and even critical scholars avoid analyzing the racial power of law.41 The absence of scholarly analysis relating to race in the premier international law journal in the United States, in my view, makes discussions of race and racial domination in international law invisible. These exclusions were also noted in the report of the 2014 Governance Reforms Committee of AJIL, appointed by then ASIL President Donald Francis Donovan, that noted that there was a perception that AJIL was “‘closed shop,’ made up of those with similar ‘mainstream, traditional’ perspectives who tend to publish and reproduce themselves, and where more ‘innovative scholarship’ is unwelcome.”42 The members of that committee were: Jane Stromseth (Chair); Jose Alvarez (Ex Officio); Antony Anghie; Mahnoush Arsanjani; Christopher Borgen; Joan Donoghue; Larry Helfer; Edward Kwakwa; Natalie Reid; and Richard Steinberg. The deliberations of this committee’s report in the ASIL Executive Council, comprising members such as Jeremy Levitt and Makau Mutua, set the stage for the election of the first African American editor in 2014. When the first African American was elected to the AJIL Board, the Executive Council initially rejected the slate because it did not include a woman. The AJIL Editorial Board re-did the election to conform the guidance from the Executive Council.43

B. Hypothesis Two: Exclusion of Critical Scholarship Including that Relating to Race

While noting that Marxist scholarship on international law has not been accepted in mainstream academic circles, Bhupinder S. Chimni, a leading TWAIL Marxist scholar, noted that this unacceptability is “a price that critical theories in general have to pay for contesting dominant ideas and approaches.”44 He continued noting that critical approaches:

have to confront the ‘subtle censorship of academic decorum.’… the fate of other critical theories such as TWAIL, FtAIL, [Feminist Approaches to International Law], or NAIL, [New Approaches to International Law,] have only been a shade better. Indeed all critical theories are sought to be marginalized by MILS [Mainstream International Legal Scholarship]. But it is only to be expected as critical theories are ranged against the interests of dominant national and international social forces, and therefore often portrayed by the mainstream as unacceptable forms of academic dissent.45

Elsewhere, I have responded to dismissive claims that TWAIL scholarship lacks methodological clarity or that it engages in nihilist deconstruction.46 These types of critiques of critical international law scholarship are not new in AJIL. A 1945 review in the journal of W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1945 book, Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace, perhaps sums up the type of skeptical scrutiny about scholarship relating to race. P.M. Brown, of the Board of Editors, wrote about the book:

The hideous cruelties, abominable humiliations, and incredible injustices suffered by the colored race have created a bitterness that precludes an objective and fair analysis of the whole colonial problem. The author . . . has not provided a dispassionate and realistic solution . . . . The author seems to reveal a lack of realism in considering the status of the many African tribes so obviously unprepared for united political action, self-government and independence. He does not credit the colonial powers with sincerity in acknowledging their responsibilities as trustees for the education of backward peoples for full freedom and international obligations.47

Those words speak for themselves. They strongly suggest that uncovering sensitive issues of race will only sow division and that they constitute pure grievance, presumably because it is not possible to speak about race and racism objectively.48 In fact, Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg make exactly the same claim in dismissing the work of those that they call critical scholars.49

All this suggests that perhaps the proper way to research and write about international law is devoid of any emotion or reference to the racial power of law. Even more, the reviewer of the DuBois book held the views that the colored peoples of the colonies are backward, itself a racist notion, and that W.E.B. DuBois failed to give credit to the colonial powers for all they were doing! That is certainly an apology for colonialism. I may be accused of anachronism here—that I am using my twenty-first century lens to judge what this reviewer meant in 1945.50 I have two responses to that. First, 1945 was the height of the anticolonial and antiracist efforts against colonial rule in most of Asia and Africa, so these themes were already present in the intellectual discourse of the time. 51 Second, W.E.B. DuBois was one of the leading African American intellectuals of his time connecting white domination of African Americans in the United States to what he called the global color line.52 So clearly, the questions of race and racial injustice were really at the center of discussion and debate in the United States and abroad. Second, the fact that not much progress to date has been made in publishing scholarship that centers examination of the relationship between international law and race seems to have followed the historical trajectory or path dependency of no consistent practice of publishing such work.

The data I have unearthed clearly shows that the Black international tradition is underrepresented in AJIL and its online companion.53 In my view, it also shows that the intellectual authority interests of those interested in issues of race and racism in international law, and in particular those Black international lawyers who write on these subject areas, have been ignored and therefore not valued in the leading international law journal in the United States. Perhaps this research shows the relationship between power and knowledge, a topic that Edward Said powerfully wrote about in his 1978 book, Orientalism.54 For Said, Orientalism was a “sign of European-Atlantic power over the Orient.”55 It seems mainstream approaches to international law have had a similar power of epistemically erasing the perspectives of how racialized minorities have been marginalized by international law.

Further research needs to interrogate the methods of exclusion of work relating to race as well as the scholarship of minority scholars to see if this scholarship around issues of race was prevented not just by the absence of honest racial dialogue, but also by mechanisms of exclusions such as those that pose a tradeoff between quality and diversity. Further, it would be great to know if, as an imperative to maintain the quality of AJIL and AJIL Unbound, it has been necessary to police the boundaries of what is published to prevent the quality of the journal being compromised. As I will note in the conclusion, this conversation has only just commenced within the Board of Editors of AJIL.

C. Hypothesis Three: The Big or Defining Debates About International Law in the United States Have Focused on Issues Other than Race

The defining debates about international law in the United States, as represented in AJIL, have not simply focused on or zeroed in on the role and place of race in international law. That means the editors of AJIL focused on topics that they considered to be the most important. As a review of AJIL’s first century noted, the journal has a “peculiarly messianic and distinctively American, vision and thrust” traceable to its founders.56 In effect, scholarship probing the role of the U.S. as an empire that mobilized race to repress non-dominant peoples in its possessions and territories, but also and most significantly in its domestic jurisdiction, has not been a particular focus of international law scholarship in the pages of AJIL or AJIL Unbound. For example, African American scholars who were particularly interested in how the minority rights system in Europe could be a useful international legal analogy for U.S. minorities did not feature in any significant way in the pages of AJIL.57 By contrast, for European scholars who have dominated writing about the minority rights system in Europe in the interwar years, including in AJIL, the focus of their scholarship was mainly descriptive of that system outside the United States. That scholarship was never focused on the applicability of the minority rights system within the U.S. The inattention to applicability of the minority rights system for domestic minorities within mainstream international law circles is consistent with the view that civil rights apply to domestic minorities and human rights apply outside the United States.58 This distinction between domestic and international realms has a long legacy of limiting international legal scrutiny of racial inequality and racial injustice in the United States. This exceptionalism has, in my view, been part of the silencing of how domestic minorities have sought to use international law to address their racial repression and marginalization from slavery to date.59 In other words, it seems that this exceptionalism, in part, explains the absence of any critical scrutiny of issues relating to race in AJIL and AJIL Unbound to date.

In the last couple of years, a non-exhaustive list of examples of some of the big themes that have preoccupied international legal scholarship include:

- The big culture wars of AJIL were about the place of international law within the U.S. legal order, and in particular the debate between the modern and revisionist position about the status of customary international law as federal common law.60 These debate have centered on the “constitutional dimensions of U.S. foreign affairs law” and they have straddled the history of the journal from its founding.61 So American has AJIL’s focus been that a controversy is reported to have emerged within the governing board of ASIL about awarding Hans Kelsen the 1952 ASIL annual distinguished scholarship award because he “had not adopted a U.S. policy orientation.”62

- Another major AJIL theme has been the role of the U.S. in the world. This has involved questions of war (including torture, rendition in the recent past), national security, as well as humanitarian intervention every time there is a discussion about the use of force. In David Bederman’s study of the first 100 years of AJIL scholarship, he noted that contributors to the journal followed a “common script of interests and attitudes” so that when the United States entered into conflict, “the journal was a loyal and obedient commentator about American war aims and objectives, as befit the communication organ of a society that was, at one and the same time, progressive and conservative on this country’s legal engagements overseas.”63

- AJIL has also focused on the U.S.’s relationship with international institutions like the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, and the International Court of Justice.64

- Another commitment in AJIL has been a “belief in the ultimate inevitability of a community of nations living under the rule of law.”65

- AJIL has been consistently committed to international arbitration and institutions for promoting stable and predictable relations between states.66

Another of AJIL’s major points of focus has been the type of international law questions that characterize the work of the Office of the Legal Adviser in the U.S. Department of State, which is charged with providing “advice on all legal issues, domestic and international, arising in the course of the Department’s work. This includes assisting Department principals and policy officers in formulating and implementing the foreign policies of the United States, and promoting the development of international law and its institutions as a fundamental element of those policies.”67 It is important to outline this theme at some length. Bederman’s account of the first century of AJIL scholarship notes that in “view of the strong connection of some AJIL contributors to U.S. government circles, and the historical tradition of the journal as a reflection of both the progressive and conservative attitudes of ASIL, the U.S. government’s views appear to have had a fair hearing in these situations.”68 There indeed has been a rotating door between ASIL and the Legal Advisers’ office. In 2006, Lori Damrosch observed that “many of the journal’s editors . . . have previously held positions in the [State] [D]epartment’s Office of the Legal Adviser or other offices concerned with U.S. foreign relations.”69 In fact, Legal Advisers and the lawyers who serve in that office are frequently on the annual meeting program of ASIL.70 Further, one of the major receptions at the ASIL annual meeting is hosted by the Legal Adviser’s office hosted for former and current staff of the Legal Adviser’s office and their guests. A search of the Legal Adviser on AJIL indicates that the Legal Advisers’ opinions feature prominently in its pages over several decades. Unsurprisingly, many AJIL editors have served stints in the Office of the Legal Adviser. Thus Carl Landauer remarks that “the journal’s articles often seem to have been written in an antechamber of the State Department.”71 It is notable that AJIL has a long-standing relationship to the U.S. State Department. To cite Benjamin Allen Coates again, he notes in the early twentieth century there was a “large number of government officials in the ASIL’s leadership [and the] State Department took out 450 subscriptions to the AJIL . . . and in the process improving the society’s financial position.”72 Coates notes that James Brown Scott, who was its first Editor in Chief (1907 to 1924) and who contributed money to found it,73 wrote AJIL editorials in its early years to make sure they did not criticize the Department of State, so that those subscriptions were not cancelled.74 Indeed, ASIL’s early history was closely linked with American power, as evidenced by the fact that the U.S. Secretary of War Elihu Root served as ASIL’s founding President, three of its Vice Presidents were Supreme Court Justices, three former Secretaries of State, and a future U.S. President.75 As Carl Landauer notes, the early officers of ASIL and editors of AJIL “were part of the interlocking directorate of the US legal and international relations establishment, and very much part of what has been identified as a new American ‘gentry’ class.”76

D. Hypothesis Four: Color-Blindness Has Been the Default Mode of International Legal Scholarship

Another hypothesis is that color-blindness has been the default norm in the production of international law scholarship published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. This is consistent with the fact that the U.S. government has a long history of limiting scrutiny of its record of domestic racial inequality, racial injustice, and ongoing marginalization of women and Indigenous peoples through international law.77 In effect, my findings suggest that AJIL and AJIL Unbound consciously or unconsciously raise the possibility that they reinforce the white status quo understanding of international law.78

As I have noted elsewhere recently, domestic U.S. law was constructed on assumptions that white identity embodied the ideal expression of humanity in terms of morality, progress, and civilization. Likewise, imperial international law was constructed on the basis of white racial superiority—as rational stewards of the territories of non-Europeans—and on the basis of racist myths of indigenous savagery, primitivism, and pathology. Hence, just as slavery dehumanized African Americans as degenerate and outside the boundaries of humanity in the construction of the United States as a white racial state, European and white international law was constructed to superintend over “backward” non-European peoples who were considered to live outside the bounds of humanity and therefore outside of sovereignty.79

IV. Conclusion

In this Essay, I have used the social science approach to studying international law recommended by Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg to show the near total silence of issues of race in the pages of AJIL and AJIL Unbound. I have hypothesized that the exclusion of issues of race from the pages of the leading international law journal can be accounted for along four dimensions. First, this absence reflects the conscious exclusion of African Americans in ASIL in the first six decades of its existence, as the 2020 Richardson Report found.80 Second, it is the result of the stringent scrutiny that international law scholarship relating to racial subordination in international law has faced in AJIL and AJIL Unbound. Third, the big or defining debates about international law in the U.S. have focused on issues other than race. And fourth, color-blindness has been the default view of American international law scholarship as represented in the journal.

This Essay shows two things. First, that Abebe, Chilton, and Ginsburg’s social science approach can be fruitfully applied to answer questions that critical international law scholars are interested in. Second, that in tracing the legacy of race in international law, as I have done in this article, Abebe, Chilton and Ginsburg’s distinction between the neutrality of the scientific methodology they subscribe to, on the one hand, and the normativity of critical approaches that they argue characterizes other approaches, on the other hand, cannot be sustained. This is because the choice of the subject matter that a social science approach takes necessarily excludes other choices. Making that choice is therefore a process of inclusion as well as of exclusion. To the extent that a choice must be made, the selection itself is normative. In addition, the choice of what gets published and what does not, as this Essay has tried to show, can itself be an exclusionary process—something that cannot be normatively or ideologically neutral.

This Essay has shown that AJIL and its companion AJIL Unbound have published little on race in over 100 years. Yet, race is heavily embedded in how many rules of international law were formulated and the manner in which it is applied to date. This absence of articles relating to race reflects choices that have effectively discouraged, if not silenced, the production of scholarship on race and international law. That outcome, I contend, is not inevitable, natural, and necessary, but is perhaps rather a reflection of the choices about what types of knowledge in international law matter enough to be published in the pages of AJIL and AJIL Unbound.

So, what can be done about this exclusion of scholarship probing the role of race in AJIL and AJIL Unbound? Elsewhere, I have made the case that CRT scholars and TWAIL scholars should work together to combat the “all-too-often mainstream efforts to provincialize, define, and box critical approaches—especially when they delve into issues of race and identity—as marginal and irrelevant, rather than as significant contributions that challenge expand their respective fields.”81 Already a number of recent events have been convened between TWAIL and CRT scholars to explore their overlapping interests, and part of that conversation is set to be published as a symposium issue of the UCLA Law Review.82 This is a great start.

Within AJIL, on October 5, 2020, the Executive Committee of Blacks of the American Society of International Law (BASIL)83 wrote to the Editors in Chief of AJIL in the following terms:84

[T]aking into account the progress made since 2014 when the first African Americans were elected as Editors of the American Journal of International Law, BASIL calls upon the Editors of the American Journal of International Law:

- To continue to make diversity and inclusivity a consideration, particularly of African Americans, in those selected for nomination to be AJIL Editors;

- To continue to make diversity and inclusivity a consideration, particularly of African Americans, among those elected to be AJIL Editors;

- To ensure that appointive positions at the discretion of the Editors in Chief in the Journal (such as for Section Heads, Associate Managing Editors, committee chairs, and other leadership positions) reflect the diversity of ASIL’s membership and in particular of African Americans and critical race scholars;

- To in particular ensure that the appointment of Associate Managing Editors include African Americans since this has become an informal pipeline for election to become Editors and yet no African Americans have served in this role;

- To ensure an open, more transparent application process for Associate Managing Editors (comparable to ASIL’s approach to openly advertising leadership positions) —e.g., advertised through historically-Black law schools, the National Bar Association, BASIL, and other appropriate institutions that may provide a gateway for African American and other underrepresented lawyers who specialize in international law;

- To avoid the types of word-of-mouth (and “old boy’s network”) hiring approaches that have been found illegal under U.S. civil rights law, as such hiring processes served to exclude, rather than open up the pipeline of opportunity;

- To in particular ensure that the appointment of the Nomination Committee for the election of new Editors is inclusive and diverse and, to the extent possible, especially when African American editors are finalizing their terms of office or when they have decided not to seek re-election, that African American Editors are part of the Nominating Committee;

- To continue to add to rather than to reduce the number of African Americans on the Board of Editors to avoid the legacy of exclusion of African Americans in the Board of Editors; and

- To continue maintaining African American nominees eligible for election put forward by the Nominating Committee but not elected for consideration in subsequent elections.85

An ad hoc committee on Diversity in AJIL was convened in late 2020 with a mandate to look into “how AJIL should promote racial and other forms of diversity in the process for nominations, elections to the Board, and selection of section heads and editorial positions on Unbound.”86 Although BASIL’s letter noted that “we would be delighted to see articles on the types of issues raised by critical race theorists in AJIL that have so far not featured in the pages of the Journal,” issues of content were excluded from the remit of the ad hoc committee on diversity.87 After several months of intensive consultations, the ad hoc committee report to the full AJIL Board in March 2021. The report made eight recommendations:

Recommendation (1): Diversity Statement. Replace the Lillich Guidelines with a Diversity Statement that can be used to guide or question future decisions:

Sample language: The American Journal of International Law is committed to being the preeminent publication on international law in the United States. Toward that end, the Journal will select highly qualified individuals, who have diverse backgrounds and perspectives (along multiple dimensions), to participate in decisionmaking on the Board of Editors and in other management or editorial positions. This commitment to diversity is not only in the service of excellence but also consistent with fundamental non-discrimination norms in the field of international law.

Send this Diversity Statement to nominees for election to the Board, with the statement on active service, in order to establish expectations for Board membership.

Recommendation (2): Cultivate Diverse Talent. Work with relevant ASIL groups and programs (e.g., BASIL, WILIG, MILIG, and “new voices”) to provide mentorship and advice to interested scholars who are of color (especially African American) or are not cisgender men. Include a diverse range of article reviewers when going outside the Board, as one way to identify possible future candidates for the Board.

Recommendation (3): Transparency in Nomination and Selection Criteria. Publicize information about the criteria for being nominated or selected to the Board or to other management or editorial positions, so that qualified candidates who are not well networked can more easily put themselves forward.

Recommendation (4): Open the Processes for Selecting Section Heads and Editorial Positions for AJIL Unbound. Consider publicizing (at least to members of the Board) when these positions become available so that the pool of candidates can be expanded and diversified. Also consider involving some members of the Board in the appointment decisions.

Recommendation (5): Nomination Committee Diversity Consideration. Ensure that the Nomination Committee is diverse and require it, when presenting the candidates for selection to the Board, to describe the steps it took to include a slate of candidates who are diverse among many dimensions, including race (especially African Americans) and gender.

Recommendation (6): Create an Inclusive and Equitable Environment on the Board. Provide more opportunities for Board members to interact and participate in decisions relating to the Board. For example, consider using semiannual meetings to discuss strategic decisions, best practices for reviewing manuscripts, or opportunities for future engagement and involvement. In addition, encourage Board members to present their own ideas for the Journal; avoid creating an environment (actual or perceived) in which only a small subset of Board members shape the content of the Journal.

Recommendation (7): Do Not Backslide. Given the progress that has been achieved in diversifying the Board, create the expectation that future Board Elections will build on rather than undercut this progress; perhaps use as a baseline goal the 2020-2021 composition of the Board. Encourage Board members to disclose on a voluntary basis their racial, ethnic or other forms of diversity to help the Journal track progress in diversifying the Board.

Recommendation (8): Regular Diversity Review. Institute a regular process for reviewing, perhaps every three years, the diversity on the Board and in other editorial and management positions and for recommending further action, as necessary.

Recommendation (9): Diversity in Content. Institute a process for considering whether and, if so, how AJIL should try to diversify its content such that it includes a broader range of topics and methods of analysis, including but not limited to those relating to gender, race, and ethnicity.88

In short, AJIL’s Editorial Board has instituted a process to address many of the issues raised in the BASIL letter and which, in my view, have prevented AJIL and AJIL Unbound from publishing scholarship critically analyzing the role of race in international law. That said, as important as the process is for addressing issues of content in AJIL and AJIL Unbound, the measure of success is when AJIL and AJIL Unbound regularly publish issues of race and identity as often as they publish on black letter law issues.

The foregoing nascent efforts within AJIL, including the election of two female African American editors and the first indigenous American as an editor,89 may offer some hope that there will be momentum to dismantle to legacy of exclusion of content relating to race in the pages of the journal and in AJIL Unbound as well. Ultimately, more scholarship needs to probe why issues relating to slavery, race, and imperialism, which have all intimately shaped international law, have not been featured in any significant way in the pages of AJIL and AJIL Unbound. This unfortunate state of affairs has continued even as there continues to be a growing body of scholarship on these themes published in leading publishing houses as well as articles published in many other reputable journals and blogs.90 In fact, it is telling that the international legal ramifications of Black Lives Matter were covered by the European Journal of International Law91 and the blog Just Security,92 but not by the AJIL or AJIL Unbound in any of any significant way. Hopefully, the conversations that have begun within the Editorial Board of AJIL and AJIL Unbound will address these more than century-long exclusions and silences and begin to overcome them.

- 1AJIL was first published in 1907, whereas AJIL Unbound was first published in 2014.

- 2See, e.g., Christiane Wilke, Reconsecrating the Temple of Justice: Invocations of Civilization and Humanity in the Nuremberg Justice Case, 24 Can. J.L. & Soc’y 181 (2009).

- 3Benjamin Allen Coates, Legalist Empire: International Law and American Foreign Relations in the Early Twentieth Century 83 (2016).

- 4Id. at 43.

- 5Id. at 1.

- 6Carl Landauer, The Ambivalence of Power: Launching the American Journal of International Law in an Era of Empire and Globalization, 20 Leiden J. Int’l L. 325, 328 (2007).

- 7Coates, supra note 3, at 3. Coates concludes that lawyers were therefore “ideological actors as much as technical advisers.” Id. at 180. See D.J. Bederman, Appraising a Century of Scholarship in the American Journal of International Law, 100 Am. J. Int’l L. 20, 62 (2006) (“American international lawyers, speaking through AJIL, have advanced U.S. policy initiatives, doctrines and positions even while vehemently disagreeing with some. Aside from these specific situations, these writers have tended (although by no means uniformly…) to believe that the project of international law is a worthwhile one that holds promise for world order.”).

- 8See, e.g., Wilke, supra note 2, at 181. In this article, Wilke shows that “the 1918–1947 volumes of the American Journal of International Law (AJIL), published by the American Society of International Law, reveal that the concept of civilization was frequently used in the period following the end of World War I, declined in popularity at the end of the 1920s, and experienced a remarkable renaissance in the decade between 1938 and 1947.” Id. at 187. The premise in the article is that the “standard of civilization” that was “dominant in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth century international law . . . [was] an expression of the idea that international law is a body of norms for civilized states only.” Id. at 186. For another analysis of how imperialism was redefined as civilization, see Mohammad Shahabuddin, The ‘Standard of Civilization’ in International Kaw: Intellectual Perspectives from Pre-War Japan, 32 Leiden J. Int’l L. 13 (2019); Antony Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law 67, 84–86 (2004) (noting that independent non-European states like Japan could be brought into the realm of international law if they met the “requirements of the standard of civilization of, and being officially recognized by, European states, as proper members of the family of nations” and discussing how these non-European societies were required to meet the standard of civilization). This standard of civilization shifted in the nineteenth century. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the criteria included Christianity. In the second half, it was predicated on “European culture and institutions—in particular, the ability to furnish Europeans with legal, economic, and later, political institutions to which they had become accustomed.” Rose Parfitt, Empire des Nègres Blancs: The Hybridity of International Personality and the Abyssinia Crisis of 1935-36, 24 Leiden J. Int’l L. 849, 858 (2011).

- 9Mohsen al Attar, Subverting Racism in / Through International Law Scholarship, Opinio Juris (Mar. 3, 2021), https://perma.cc/M9KT-N3Q9; see also Mohsen al Attar, “I Can’t Breathe”: Confronting the Racism of International Law, Afronomicslaw (Oct. 2, 2020), https://perma.cc/6HAK-GLQB.

- 10Further, al Attar argues that “[n]on-Eurocentric perspectives enjoy lesser status, unless they are measured against a European benchmark and preferably by a white scholar. Despite international law’s brutal history and generations of Critical Race Theory, race receives minimal uptake among international lawyers. Last, many non-racialised scholars fail to appreciate how their approach toward racialised academics places us at an unfair disadvantage.” al Attar, Subverting Racism in / Through International Law Scholarship, supra note 9.

- 11Am. Soc’y Int’l L., The Richardson Report, Final Report from the ASIL Ad Hoc Committee Investigating Possible Exclusion or Discouragement of Minority Membership or Participation by the Society During Its First Six Decades (2020) [hereinafter The Richardson Report]. This report was drafted by an ad hoc committee appointed pursuant to American Society of International Law Executive Council Resolution of 4th April 2018. Its mandate was to investigate possible exclusion or discouragement of minority membership or participation in the Society during its first six decades. The report was unanimously adopted by the ASIL Executive Council in its meeting on April 2, 2020.

- 12HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library is available to subscribers through the HeinOnline platform. A description of the content is available at https://perma.cc/Y2GH-LP8S.

- 13See American Journal of International Law, Cambridge Core, https://perma.cc/5ANB-SDPU; AJIL Unbound, Cambridge Core, https://perma.cc/92S4-Z553.

- 14I restrict my analysis to race, rather than to terms such as imperialism and colonialism because my central inquiry relates to establishing if there has been blindness to race and its central role in shaping international law and justifying other regimes of subordinating non-white peoples including slavery and colonialism in the scholarship published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound.

- 15“Articles” includes “Lead Articles,” “Notes” includes “Contemporary Practice of the United States Relating to International Law,” “Comments” includes “Editorial Comments,” and “Reviews” includes “Book Reviews.”

- 16The AJIL and AJIL Unbound content omitted in my analysis, such as Miscellaneous items, Tables of Contents, and Legislation, does not usually include commentary and is included in AJIL primarily for informational purposes. The content was excluded here since it did not provide analysis that would contribute to establishing the answer to my primary query in this Article—namely, whether the content published in AJIL and AJIL Unbound has probed the racist underpinnings of international law, as well as the racial hierarchies upon which international law was constructed.

- 17Because there is a two-year embargo on the full text of the AJIL in HeinOnline, the full texts of the most recent documents included in the set were examined in Westlaw.

- 18When “*” is used as a search term without limiting the results to certain section types, then 7,535 results appear for AJIL, and 571 for AJIL Unbound. However, to ensure a proper comparison with the documents individually reviewed, these baseline totals were limited to Articles, Comments, Notes, Reviews, and Editorials. Thus, for the purposes of this analysis, there were 5,109 total documents in AJIL, and 568 documents in AJIL Unbound.

- 19For a leading text demonstrating this, see Anghie, supra note 8.

- 20James Thuo Gathii, Writing Race and Identity in a Global Context: What CRT and TWAIL Can Learn from Each Other, 67 UCLA L. Rev. 1610, 1613 (2021).

- 21See James Thuo Gathii, The Agenda of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL), in International Legal Theory: Foundations and Frontiers (Jeffrey Dunoff & Mark Pollack eds., forthcoming 2021).

- 22Anghie, supra note 8, at 103.

- 23See generally Keisha N. Blain et al., New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition (2018).

- 24There is also no evidence that the quality of scholarship on race and international law is the reason that accounts for this legacy of exclusion. To make such an argument is to claim that scholarship on race is inferior or that scholars, especially scholars of color interested in producing this scholarship, are lazy and have not produced such scholarship. In fact, there is a strong Black tradition of international law. For examples of scholarship on race and international law that prove the existence of such scholarship, see Adrian Katherine Wing, Critical Race Feminism and the International Human Rights of Women in Bosnia, Palestine and South Africa: Issues for LatCrit Theory, 28 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 337 (1996); Branwen Jones, Race in the Ontology of International Order, 56 Pol. Stud. 907 (2008); Chantal Thomas, Causes of Inequality in the International Economic Order: Critical Race Theory and Postcolonial Development, 9 Transnat’l L. & Contemp. Problems 1 (1999); Ediberto Roman, A Race Approach to International Law (RAIL): Is There Need for Yet Another Critique of International Law?, 33 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1519 (2000); Ediberto Roman, Reconstructing Self- Determination: The Role of Critical Theory in the Positivist International Law Paradigm, 53 U. Miami L. Rev. 943 (1999); Edwin D. Davis & Betty Punnett, International Assignments: Is There a Role for Gender and Race in Decisions?, 6 Int’l J. Hum. Res. Mgmt. (1995); Gil Gott, Critical Race Globalism? Global Political Economy, and the Intersections of Race, Nation and Class, 33 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1503 (2000); Henry J. Richardson III, Excluding Race Strategies from International Legal History: The Self-Executing Treaty Doctrine and the Southern Africa Tripartite Agreement, 45 Vill. L. Rev. 1091 (2000); Henry J. Richardson III, Reverend Leon Sullivan’s Principles, Race, and International Law: A Comment, 15 Temple Int’l & Comp. L.J. 55–80 (2001); Tayyab Mahmud, International Law and the Race-Ed Colonial Encounter: Implementation, Compliance and Effectiveness: International Dimensions of Critical Race Theory, 91 Am. Soc’y Int’l L. Proc. 414 (1997); James Thuo Gathii, International Law and Eurocentricity: Book Review, 9 Eur. J. Int’l L. 184 (1998); James Wilets, From Divergence to Convergence? A Comparative and International Law Analysis of LGBTI Rights in the Context of Race and Post-Colonialism, 21 Duke J. Int’l & Comp. L. 631 (2010); Jordan Paust, Race-Based Affirmative Action and International Law, 18 Mich. Int’l L. Rev. 659 (1996); Keith Aoki, Space Invaders: Critical Geography, The “Third World” of International Law and Critical Race Theory, 5 Vill. L. Rev. 913 (2000); Kim Beneta Vera, From Papal Bull to Racial Rule: Indians of the Americas, Race, and the Foundations of International Law, 42 Cal. W. Int’l L.J. 453 (2011); Makau Matua, Critical Race Theory and International Law: The View of an Insider-Outsider, 45 Vill. L. Rev. 841 (2000); Martti Koskenneimi, Race, Hierarchy and International Law: Lorimier’s Legal Science, 27 Eur. J. Int’l L. 415 (2016); Penelope Andrews, Making Room for Critical Race Theory in International Law: Some Practical Pointers, 45 Vill. L. Rev. 855 (2000); Ruth Gordon, Critical Race Theory and International Law: Convergence and Divergence, 45 Vill. L. Rev. 827 (2000); Robert Knox, Civilizing Interventions? Race, War and International Law, 1 Cambridge Rev. Int’l Aff. (2013); Ronit Lentin, Palestine/Israel and State Criminality: Exception, Settler Colonialism and Racialization, 5 St. Crime J. 32, (2016); Sankaran Krishna, Race, Amnesia, and the Education of International Relations, 26 Alternatives 401 (2001); Siba Grovogui, Come to Africa: A Hermeneutics of Race in International Law, 26 Alternatives 425 (2001); Taylor Natsu Saito, From Slavery and Seminoles to AIDS in South Africa: An Essay on Race and Property in International Law, 45 Vill. L. Rev. 1135 (2000); and Twila Perry, Transracial and International Adoption: Mothers, Hierarchy, Race and Feminist Legal Theory, 10 Yale J.L & Feminism 101 (1998). For books on the topic, see Alexander Anievas, Race and Racism in International Relations: Confronting the global colour line (2015); Geeta Chowdry & Sheila Nair, Power, Postcolonialism and International Relations: Reading Race, Gender and Class (2002); and Sundhya Pahuja, Corporations, Universalism and the Domestication of Race in International Law, in Empire, Race and Global Justice (Duncan Bell ed., 2019). For additional resources, see Jeanne M. Woods, Introduction: Theoretical Insights from the Cutting Edge, 104 Am. Soc’y Int’l L. Proc. 389 (2010); International Dimensions of Critical Race Theory, 91 Am. Soc’y Int’l L. Proc. 408 (1997); Henry J. Richardson III, African Americans and International Law: For Professor Goler Teal Butcher, with Appreciation, 37 Howard L.J. 217 (1994).

- 25In that research, I answer the following questions: whether Black scholars are cited by the most prominent scholars, and whether the work of Black scholars is not reproduced or acknowledged in leading casebooks.

- 26See generally Yussuf Naim Kly, International Law and the Black Minority in the U.S. (1985).

- 27See generally A Popular Guide to Minority Rights (Yussuf Naim Kly ed., 1995).

- 28Just because a scholar is Black does not mean that they represent Black people or, for that reason, all Black people. See Olúfémi O. Táíwò, Being-in-the-Room Privilege: Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference, 108 The Philosopher 61 (2020) (writing about “standpoint philosophy”).

- 29The Richardson Report, supra note 11, at 8–9.

- 30See, e.g., Eddie R. Cole, The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom (2020).

- 31See Henry J. Richardson III, Letter to the Editor, 94 Am. J. Int’l L. 99, 99 (2000) (expressing disappointment that perspectives of “people of color” were not represented).

- 32Id. For another recounting of this episode, see Woods, supra note 24.