The Identification of Customary International Law: Institutional and Methodological Pluralism in U.S. Courts

It is well established that there is a consensus, two-element approach to the identification of customary international law. Among international courts and organizations, a customary rule is identified based on evidence of a general practice by states, which is accepted as law. Customary international law, however, is also subject to identification at the national level. For centuries, questions regarding the existence and content of customary international rules have arisen in national courts. Given their own institutionalized methods of resolving legal ambiguity, national courts are thus routinely faced with a normative conflict: is the appropriate method for identifying rules of customary international law located in the national or international realm? By using customary international law as a case study, this Article offers a more nuanced understanding of how international law is localized into U.S. courts. While prevailing theories posit that the diffusion of international rules results in national acceptance or rejection, this empirical analysis demonstrates how normative pluralism may also generate hybridization. As international integration accelerated after World War II, U.S. judges increasingly relied on hybrid models of decision-making that sought legitimacy within both the national and international legal systems.

I. Introduction

It is well established that customary rules are a source of international law. What is less settled is how to identify the existence and content of such rules. Indeed, the very premise of customary international law (CIL)—that the rules are not necessarily legislatively or textually confirmed—reveals the inherent difficulty of identifying extant rules. This identification question has recently generated renewed interest in the consensus international approach to identifying the rules of CIL, or, put differently, the customary approach to identifying CIL.

Under the prevailing approach at the international level, a rule of CIL is identified based on two elements: (1) evidence of a general practice by states that is (2) accepted as law.1 Although there is some disagreement around the margins, the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice, as well as the consistent practice of numerous other international bodies, reflects international consensus on this two-element approach.

The International Law Commission (ILC) has recently worked to textually confirm and develop the consensus international method, in part because of divergent approaches at the national level.2 National divergence is seen as a threat to custom’s stability and legitimacy and is thought to arise from ignorance among national judges about the international approach.3 In line with positivist and process-based theories of international law, the prevailing view is that there is a singular, true international approach that national judges have internalized or purposively decided to adopt.4 This Article challenges such actor-centric theories by examining whether the experience of U.S. courts regarding identification questions is more phenomenological5 than previously understood.

The analysis herein is motivated by sociological institutional theory, specifically its world society and organizational variants. World society theory proposes a structural, phenomenological explanation for the diffusion and replication of international models over time. In an increasingly integrated world, global models take myriad forms, including individual rights as the model form of social justice and the university as the exemplary form of higher education.6 According to sociological institutionalism, global models are enacted at the national level because of their institutionalization in world society, not because of national needs or interests. Similarly, organizational institutionalism posits that, in response to decisional uncertainty, organizations mimic institutionalized models of their organizational field.7 In a field like the U.S. legal system, exogenous and endogenous models of appropriate behavior, rather than purposive rational action by individual judges, shape decision making.8

By drawing on institutional theory, this Article develops how the two-element approach to identifying CIL is an institutionalized model of world society that has structured action in the international legal system for the past century. Critical to this isomorphism was the international development of typified language relating to customary law’s two constitutive elements. To signal legitimacy within the international arena, organizations, including courts and arbitral tribunals, incorporate the legitimated methodology of the two-element approach.

Along with its institutionalization at the international level, however, CIL is also subject to social definition and application at the national level. For centuries, questions regarding the existence and content of customary international rules have arisen in national courts in a variety of substantive areas, including on issues of immunity, international crimes, and human rights.9 National courts, which have their own institutionalized rules for resolving legal ambiguity, have thus been faced with an apparent institutional contradiction: is the appropriate institutionalized model for identifying CIL located in the national or international realm? This Article examines how plural institutionalized models generate judicial uncertainty and variation in practice.

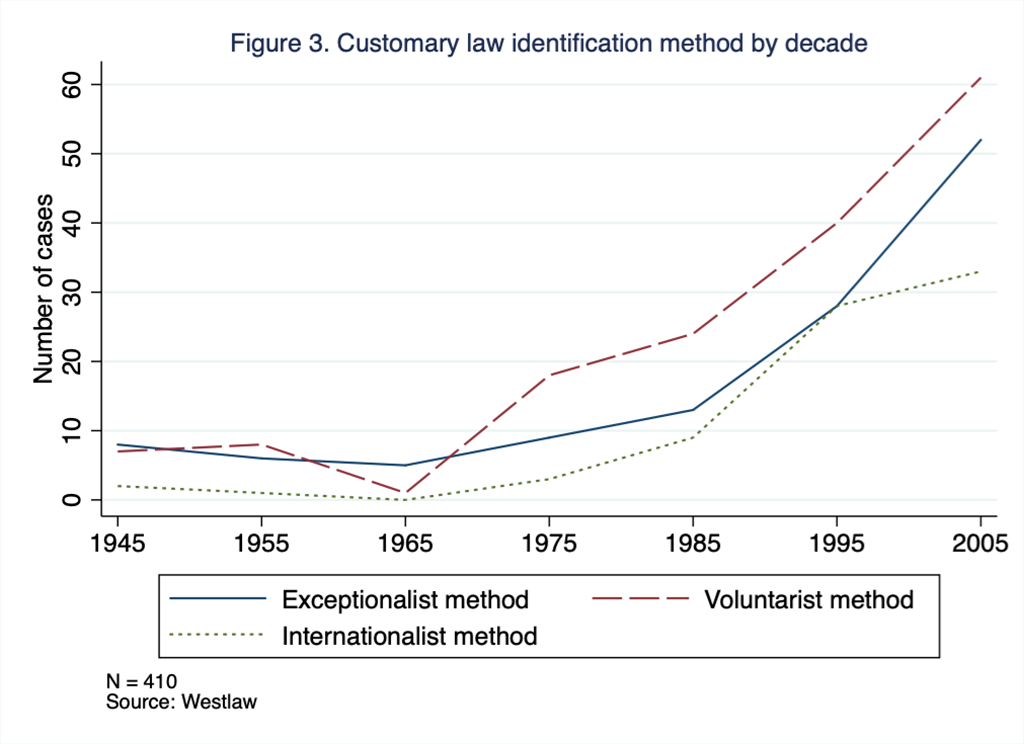

To better understand the variation, this Article draws on a systematic content analysis of over three hundred U.S. federal court cases decided between 1945 and 2015 in which the existence of a rule of CIL was in question. On the basis of those cases, the Article proposes a typology of identification approaches and examines how methodological variation has shifted over time. The three approaches—developed herein as the “internationalist,” “voluntarist,” and “exceptionalist” approaches—reflect distinctive treatments of the internationalized model.10 The internationalist variant reflects adoption of the international method of rule identification; the voluntarist approach adapts the internationalized model to accommodate institutionalized decision-making logics of the U.S. legal system; and the exceptionalist approach rejects the international model in favor of a national approach.

Using that typology, this Article seeks to develop a more nuanced understanding of how institutional pluralism shapes judicial decision-making and the evolution of international law in the U.S. courts. As the invocation of international norms in U.S. courts has increased since World War II, there has been a significant increase in judicial reference to the international method. Yet the prevailing approach has been the hybrid voluntarist model, which requires confirmation that U.S. practice adheres to the internationally derived rule. This pattern of hybridization has significant implications for the usage, content, and legitimacy of international law in U.S. courts, as well as the normative coherence of the international legal system.

The Article proceeds in four parts. Section II introduces the sociological institutional theory that informs the analysis. Section III elaborates the consensus international approach to the identification question. Section IV considers how plural institutional methods have shaped the treatment of international law in U.S. courts. Lastly, Section V develops a typology of U.S. approaches to the identification question.

II. International Legal Norms as Institutionalized Models of World Society

Sociological institutionalism proposes that behavior is shaped by institutionalized models that take on a “rule-like status in social thought and action.”11 Such models operate at the cultural level and inform what is considered rational, legitimate, and normative. Unlike realist theories of action that emphasize how interests generate behavior—and view institutions as epiphenomenal of such behavior—neo-institutional theory proposes that action is structured by culturally constituted logics of appropriateness.12 As such logics diffuse, they become taken-for-granted moral assumptions that are folded into the fabric of society and into the decisions of organizations and individuals.

A core proposition of neo-institutional theory is that its explanatory power transcends societal levels. The influence of legitimated institutionalized models can be observed and tested across global, national, and local cultures. For example, the theory’s propositions have motivated studies on the extent of homogeneity across world culture, as well as across specialized organizational fields at the local level.13 While orthodox institutionalisms suggest that actors unconsciously and unknowingly enact models, variants of the theory have considered whether institutions instead constrain the range of thinkable alternatives. In other words, as it concerns the well-trodden dialectic between structure and agency, institutionalisms vary in their emphasis on structural influence, but their common conviction is that institutionalized environments shape what is all too often understood to be simply agentic, purposive behavior.14

A. Neo-Institutional Theory’s World Society Variant

Over the past half-century, neo-institutional scholarship has demonstrated how linkages to world society explain the diffusion of models of action across the globe. As the international community integrated following World War II, professionals working through and within international governmental and non-governmental organizations developed models in a broad range of fields of global concern.15 Among other examples, the university became the model of higher education around the world, individual and human rights became the unified measure of social justice, and hyper-rationalized management displaced traditional bureaucracy as the optimal organizational form for progress. These international models were developed to homogenize and standardize expectations of behavior internationally and stabilize the world order.16

While national adoption of global models is often styled as a functional solution to a pressing social problem, or as agentic processes of internalization or adoption,17 world society theory proposes that national enactment of international models is often more ceremonial than real. The ordered realism baked into national implementation is constructed and supported by rationalized myths of the global polity.18 Empirical studies have demonstrated that there is considerable disjunction between the ceremonial adoption of global models in areas such as human rights, environmentalism, education, and the on-the-ground practices of national governments.19 From the perspective of institutional theory, this decoupling is a necessary feature of global society, as it maintains universalistic notions of common rationality grounded in national sovereignty and individual actorhood.20 With time, however, the institutionalized models often penetrate local societies and become the rationalized model of behavior across organizational levels.

B. Translation, Editing, and Organizational Analysis

One way in which variation is theorized to occur is through institutional pluralism. Models are developed within particular societal sectors—such as world society, national legal systems, or professions—before interaction between sectors leads to friction and contestation.21 For organizations embedded within multiple normative orders with conflicting institutionalized logics, the taken-for-granted assumptions of one environment may conflict with those of another.22 Many international legal scholars understand this contestation as a process of replacement, whereby a dominant model takes the place of another model, typically through processes of persuasion or socialization.23 Yet, organizational institutionalism has developed how contestation may result in hybridization rather than replacement—pluralism may generate hybrid forms that seek legitimacy in multiple environments.24

In the context of world society theory, Scandinavian institutionalism usefully explores two processes by which global models are adapted to local environments. The first is a process of “translation”—the diffused model remains largely intact but is not “passively transferred wholesale from one setting to another.”25 And the second is a process of “editing”—externally derived models are edited and actively reshaped by local participants.26 According to such accounts, individuals remain constructed by external sources and are not atomistic actors with a priori interests that determine behavior.27

The upshot of the foregoing is that institutionalization of a global model, if it occurs, may be a haphazard, messy process that is not nearly as systematic or purposive as actor-centric theories suggest.28 In contrast to realist theories of interest-driven adoption and compliance, neo-institutional theory offers a more dynamic, nuanced alternative for understanding the reconciliation of institutional contradictions at national or local levels.29 What prevails will not necessarily be the model that most efficiently addresses local needs, nor the model that reflects instrumental interests, but instead the model that posits that organizational behavior is shaped by externally derived, plural, and often shifting conceptions of legitimacy30 within the organizational field.31 Indeed, as organizations face choices, they refer to exogenous models of legitimate behavior from those in comparable situations. And as models are adapted and diffused through an organizational field, the hybridized, plural logic comes to be presented in rationalistic terms. In the process, the hybrid model may ultimately come to be seen as the legitimate and rational model of behavior.32

Because of its particular relevance to this Article, it is also worth noting how neo-institutional theory departs from old institutionalisms, including legal process theories that inform contemporary international law scholarship.33 While there are several core differences, the salient one for this Article is that new institutionalisms move away from socialization theories that focus on normative persuasion and internalization as the basis for behavior.34 Instead, neo-institutionalism suggests that models inform organizational choices by structuring menus of legitimate and taken-for-granted rules of behavior.35 Rather than persuading actors of a model’s functional or moral appropriateness, institutional environments create the lenses through which actors view the world and understand categories of action and thought, rather than persuading purposive actors.36 Institutionalization remains iterative and interactive but is less purposive or normative than previously understood.

III. The International Approach to the Identification of Customary International Law

International law began as a set of customary rules that developed external to national legal fields. The law of nations—as international law was previously known—was comprised of supranational rules relating to international questions such as the navigation of the high seas and diplomatic relations. Until the relatively recent proliferation of treaties, most such rules were uncodified. In effect, they were institutionalized rules of the international community of nations—taken-for-granted assumptions about appropriate behavior among nation states.

Since World War II, many customary rules have been formalized in multilateral treaties, yet much of CIL remains unwritten. Faced with the attendant uncertainty of applying unwritten rules, the two main international courts of justice—the Permanent Court of International Justice and the International Court of Justice (ICJ)—developed a guiding standard for identifying the existence and content of such rules that has structured organizational practice within the international field for the past century.37 While the initial formulation of the international model was the product of conscious design, its taken-for-grantedness in the international system has resulted from processes of legitimation and institutionalization.

Critical to the method’s institutionalization has been the evolution of typified language of CIL relating to its two constitutive elements: (1) generalized state practice and (2) opinio juris (a sense of legal obligation). To signal legitimacy within the international arena, organizations, including courts and arbitral tribunals, incorporate this methodology to demonstrate that they are “acting on collectively valued purposes in a proper and adequate manner.”38

A. The International Court of Justice

The enumeration of the sources of international law in the Statute of the ICJ is considered authoritative within the international legal system. Among the sources identified is CIL: Article 38(1)(b) provides that the Court shall apply “international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law.”39 This definition, which is identical to the one contained in Article 38(b) of the Permanent Court of International Justice, reflects a longstanding understanding of CIL as consisting of an objective and subjective element.40 Within the decentralized international legal system, state practice (the objective element) in conformity with a sense of legal obligation (the subjective element) serves as evidence of state consent to the rule in question.

ICJ jurisprudence has refined the two-element approach through regular invocation and elaboration.41 For the purposes of this Article, the Court’s nuanced deviations from the generalized model are less important than how the general approach to identification questions has become the taken-for-granted model in the international legal system. Indeed, a vast number of international courts and tribunals, including the international criminal tribunals, the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement bodies, and international arbitral tribunals, routinely and reflexively use the international model.42 As the International Law Commission (ILC) notes, “[n]otwithstanding the specific contexts in which these other courts and tribunals work, overall there is substantial reliance on the approach and case law of ICJ, including the constitutive role attributed to the two elements of State practice and opinio juris.”43 Existing jurisprudence leaves evidentiary questions open to debate, particularly as to the existence and content of particular rules, but the two-element approach has itself remained consistent, uniform, and accepted.

B. The International Law Commission

The ILC is an expert subsidiary body of the U.N. General Assembly with a mandate to codify and progressively develop international law.44 After several decades of focusing on the development of draft treaties, in 2012 the ILC turned its attention to the formation and evidence of CIL. Recognizing the important role that custom continues to play in international law, as well as the inherent difficulties of assessing the existence of such rules, the ILC set out to offer guidance to those not expert in international law on how to apply the international model.45 To do so, the Commission has drawn on state practice, the jurisprudence of international courts and tribunals, and its own prior work.

In the early stages of its work, the ILC commissioned a study of its own historical approach to CIL.46 As the principal international institution with a mandate to codify existing rules of international law,47 the ILC has routinely considered, both explicitly and implicitly, the identification question. A comprehensive survey of the Commission’s rule identification conducted by the U.N. Secretariat, on topics ranging from the law of the sea to international criminal law, reaffirmed that the two-element approach had long ago become institutionalized in the ILC’s practice.48

As of the time of writing, the ILC has adopted sixteen draft conclusions on the two-element approach to the identification of CIL.49 The draft conclusions restate the two-element approach: “To determine the existence of a rule of CIL and its content, it is necessary to ascertain whether there is a general practice that is accepted as law (opinio juris).”50

To ascertain whether there is a general practice of States, the ILC elaborates guidance on the “forms of practice,” “assessing a State’s practice,” and the generality of the practice. The form of State practice may include, but is not limited to, “diplomatic acts and correspondence; conduct in connection with resolutions adopted by an international organization or at an intergovernmental conference; conduct in connection with treaties; executive conduct, including operational conduct ‘on the ground’; legislative and administrative acts; and decisions of national courts.” 51 To assess a “State’s practice,” the ILC indicates that “[a]ccount is to be taken of all available practice of a particular State, which is to be assessed as a whole.”52 And to identify whether the “State practice” element is satisfied, the ILC borrowed from the ICJ to affirm that the “relevant practice must be general, meaning that it must be sufficiently widespread and representative, as well as consistent.”53

The ILC also elaborates the so-called subjective element, namely that the State practice is “accepted as law.” The Commission explains, in Conclusion 9, that “accepted as law” means that “the practice in question must be undertaken with a sense of legal right or obligation”54 and “is to be distinguished from mere usage or habit.”55 The Commission also explains how such acceptance is evidenced by the conduct of States, and notes that evidence could include acquiescence or the “[f]ailure to react over time.”56

To provide more fulsome guidance to those tasked with identification questions, the ILC also elaborates conclusions on the evidentiary value of international and national materials. In particular, the ILC provides scenarios in which a treaty, or multiple treaties, may reflect a rule of CIL;57 explains the evidentiary value of international organization practice;58 and sets forth the role of “subsidiary means,” including decisions of international courts and tribunals59 and scholarly writings.60

The notion of “subsidiary” in this context recognizes the ancillary role of such sources in clarifying or revealing the content or existence of the law, rather than serving themselves as a source of law.61 The most salient of such subsidiary means are the “[d]ecisions of international courts and tribunals, in particular of the [ICJ].”62 Because international judges are recognized experts in the field of international law, their decisions on questions of CIL may usefully clarify or reveal the existence or content of customary rules. Importantly, however, the ILC cautions that neither judicial pronouncements nor scholarly writings “freeze the development of the law; rules of CIL may have evolved since the date of a particular decision.”63

Finally, the Commission concludes that “regard may be had, as appropriate, to decisions of national courts concerning the existence and content of rules of customary international law.”64 The inclusion of “as appropriate” serves to caution that judgments of international courts “are generally accorded more weight than those of national courts for the present purpose, since the former are likely to have greater expertise in international law and are less likely to reflect a particular national perspective.”65 Further, the Commission noted that “national courts operate within a particular legal system, which may incorporate international law only in a particular way and to a limited extent.”66

IV. Institutional Pluralism and Methodological Legitimacy

The notion that there may be variation in how national courts incorporate international law is what animates the inquiry herein. Though CIL is an international construct, developed and refined within the international legal system, questions of CIL arise within national legal regimes across the world.67 National courts are routinely faced with questions regarding the existence and content of CIL. Courts in the U.S. and elsewhere have thus been faced with a dilemma: is the appropriate method for identifying CIL located in the national or international realm? This dilemma is particularly acute where the international model conflicts with a national system’s prevailing institutional logics for resolving legal uncertainty.

The very premise of the ILC’s project is this multiplicity of fora, which leads to inconsistent methodologies and applications of international law. Where a national judge misapplies the international approach to the identification question, the prevailing assumption at the international level is that the inconsistency is the product of ignorance or instrumentalism.68 The misuse or misapplication of customary law is attributed to a judge’s failure to know or follow the rules of the international legal regime,69 or its invocation is considered purposive, strategic behavior.70

Drawing on neo-institutionalist theory,71 this Article examines whether there is a sociological account that better explains the variation in approaches to CIL in U.S. courts. This account proceeds from the assumption that U.S. federal judges, like other organizational actors, are constructed by their institutional environments.72 The framework of the U.S. federal judiciary is itself an institutional environment, replete with “rules of appropriateness” that have become taken-for-granted.73 Such rules are the institutionalized logics that drive efforts to attain legitimacy within the legal system.74 As such, where an identification question arises in U.S. courts, there is latent institutional friction between the international and national approaches to resolving legal ambiguity.75 Plural institutional logics structure judges’ cognitive frames,76 which in turn shape how judges seek legitimacy.77

A. Legitimacy in the International Legal System

The identification of a customary rule of international law in national court implicates multiple institutional environments, along with their respective conceptions of legitimacy. Legitimacy, as used herein, refers to a “generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate, within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions.”78 Legitimacy judgments thus inform the communally sanctioned sources of law, as well as the institutionalized procedures for identifying and applying the law.79

International rules, including customary rules, draw their legitimacy from procedural fairness grounded in state consent, and substantive avoidance of conflict with jus cogens norms. The legitimate formation of rules in the international legal system involves a dialogical process amongst states and, at times, international organizations.80 This process of legitimation is decentralized and horizontal—states are understood to engage as equals in various rule-making fora, including courts and tribunals, to develop, contest, and reify norms.

Indeed, customary international rules themselves arise from legitimating processes. The emergence of a general and consistent practice accepted as law reflects the institutionalization of a norm by a critical mass of states, the social actors of the world system. Where a norm has not been adopted or acquiesced to by a generality of states, it is considered illegitimate and inapplicable as an international rule of law.81 The international legal order, as a self-regulating system, thus relies on processes of legitimation and institutionalization for stability.

B. Legitimacy in the U.S. Legal System

The U.S. legal system consists of a largely self-contained set of rules and values, backstopped by the Constitution. And the federal judiciary, in turn, derives its institutional models from the cultural processes of the U.S. legal system.82 The relevant sources of law are typically the Constitution and statutes,83 and, far less often, foreign or international law. Where U.S. law applies, there is an implicit understanding that legitimacy stems from democratic processes or the Constitution. Where foreign law applies, legitimacy is the result of mutual agreement by the parties to the dispute.84 And where international law applies, its legitimacy derives from its incorporation by reference into the Constitution or a U.S. statute.85

Once the communally sanctioned source of law has been identified, its legitimate application by U.S. federal judges is assessed in light of the concept of due process, as well as other institutionalized models of decision-making.86 Scholars and judges have developed decisional heuristics and rationalized organizing principles—referred to as legal doctrines—that seek to uphold fair process. Stare decisis—the doctrine of precedent that provides that “cases must be decided the same way when their material facts are the same”87 —is the most notable, yet doctrines of abstention,88 deference,89 logic, and interpretation,90 as well as rules of procedure and evidence in adversarial litigation, also shape decisions. Despite their rationalized origins, such rules and doctrines have long since faded into the cognitive background of U.S. courts and become taken-for-granted routines. In effect, the rules and doctrines have become institutionalized models that are reflexively invoked to seek legitimacy within the U.S. legal system and promote trust and confidence in courts’ decisions.91

While such doctrines are explicit and well understood, less prominent cognitive frames also deserve mention. Law and society scholarship, for example, has developed how social context structures a judge’s conception of fairness and justice. This context includes the social influences on judges’ decision-making, such as political preferences92 and “peer effects,”93 as well as ideological or institutional traditions, such as consistency. Indeed, organizational theories have long described the process by which social processes become taken-for-granted in various domains of work activity.94 The “juridical field, like any social field, is organized around a body of internal protocols and assumptions, characteristic behaviors and self-sustaining values.”95 As a result, its values, internal protocols, and assumptions develop into habitual patterns of behavior that structure judges’ decision-making.96

C. Institutional Pluralism in U.S. Courts

The upshot of the foregoing is that identification questions in U.S. courts implicate multiple institutional environments with conflicting conceptions of how to legitimately resolve legal ambiguity. This pluralism implicates not only substantive and procedural legal questions, but also social tension and cognitive frames. Judges immersed in an identification exercise may variously—and unknowingly—seek to comply with the legitimating scripts of their judicial circuit, the federal judiciary writ large, and the international legal system.97 Indeed, the proposition examined herein is whether the variation in approaches to the identification of CIL can be explained, in part, by the competing and evolving institutional imperatives at play.98

It is important to recall in this context that the Supreme Court itself has sanctioned the use of CIL in certain U.S. cases. In 1900, the Supreme Court famously pronounced that

[i]nternational law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination. For this purpose, where there is no treaty and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial decision, resort must be had to the customs and usages of civilized nations, and, as evidence of these, to the works of jurists and commentators who by years of labor, research, and experience have made themselves peculiarly well acquainted with the subjects of which they treat.99

While this rendered the identification and application of CIL legitimate in U.S. courts, the Supreme Court’s dictum also acknowledged how difficult customary rules are to identify and proposed its own methodology for doing so. Indeed, federal courts over the years have routinely lamented the complexity of identification questions. More recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit recognized that, as CIL “does not stem from any single, definitive, readily-identifiable source,” “the relevant evidence . . . is widely dispersed and generally unfamiliar to lawyers and judges.”100 As such, when confronted with issues as wide-ranging as piracy, counterfeiting, or expropriation, federal courts are tasked with resolving considerable ambiguity.

As noted previously, to identify the existence and content of CIL, there is no definitive source to consult, unlike for questions of U.S. statutory law or international treaty law. Further, unlike questions of U.S. common law, prior decisions of U.S. courts on the same or similar questions are neither decisive nor persuasive—at least according to the international method—as CIL is a fluid construction that requires a contemporaneous evaluation of international practice. A prior higher or peer court decision, even if internationally compliant at the time of its issuance, thus does not properly identify CIL, as it does not account for any intervening changes in state behavior on the international level. Yet, as deep-seated institutionalized logics of the U.S. legal system often generate deference to such prior decisions, uncertainty arises as to the appropriate identification procedure to follow, and courts resolve the uncertainty in varying ways.

V. Typology of Approaches Among U.S. Courts

The sociological concept of decoupling describes the disconnect that may exist between a state’s professed policy and its actual practice “on the ground.”101 In regards to the international legal system, the lack of effective, centralized compliance mechanisms produces myriad decoupling questions.102 For so-called “conventional” international law—treaties and other international agreements—decoupling is largely a question of national implementation. To assess decoupling requires an examination of any disconnect between national incorporation of the international rule and its implementation.

For CIL, by contrast, the decoupling assessment contains a predicate methodological question. As the rules by nature are not necessarily codified, variations in identification methodology beget variations in substantive law. Where national judicial methods conflict with international methods, the rules of conduct identified may also diverge, undermining the coherence of CIL. Indeed, as developed by neo-institutional theory, decoupling is particularly acute where rationalized organizational interests conflict with extra-organizational legal requirements.103 This divergence animates the ILC’s work described in Section III, as well as the analysis herein.

This analysis differs from the ILC’s work, however, in its foundational assumptions about the source of variation. Unlike positivist and legal process theories of national divergence, this Article proposes that variation flows from institutional rather than motivational pluralism. It queries whether the variation arises from overlapping, institutionalized models of the international and national legal systems, rather than individual-level attitudes or understandings as to the international method of identification.

A. Data and Methods

To test this proposition, the analysis herein considers how identification methods in U.S. federal courts co-vary with U.S. linkages to world society. The dependent variable of interest is a typology of approaches U.S. federal courts have taken to identify rules of CIL. The variable was constructed on the basis of a systematic review of 327 cases between 1945 and 2015 in which the U.S. federal courts identified or determined the existence of a rule of CIL.104 From those 327 cases, 410 identification exercises—some cases had more than one customary rule in question—were qualitatively assigned to one of three typology categories.

The typology’s three categories each reflect a distinctive method of resolving the legal ambiguity presented by identification questions. The first two—described herein as the internationalist and voluntarist approaches—reflect variants of the prevailing international model. The internationalist approach reflects complete or near-complete deference to the prevailing international approach—the assessment of the identification question simulates the analysis and logics of an international actor operating in the international community as developed by the ILC. The voluntarist approach, by contrast, translates the international approach. It employs the international model but gives weighted regard to U.S. acceptance of the norm in question. The third variant, the exceptionalist approach, rejects the internationalist approach and relies primarily on U.S. foreign relations law.

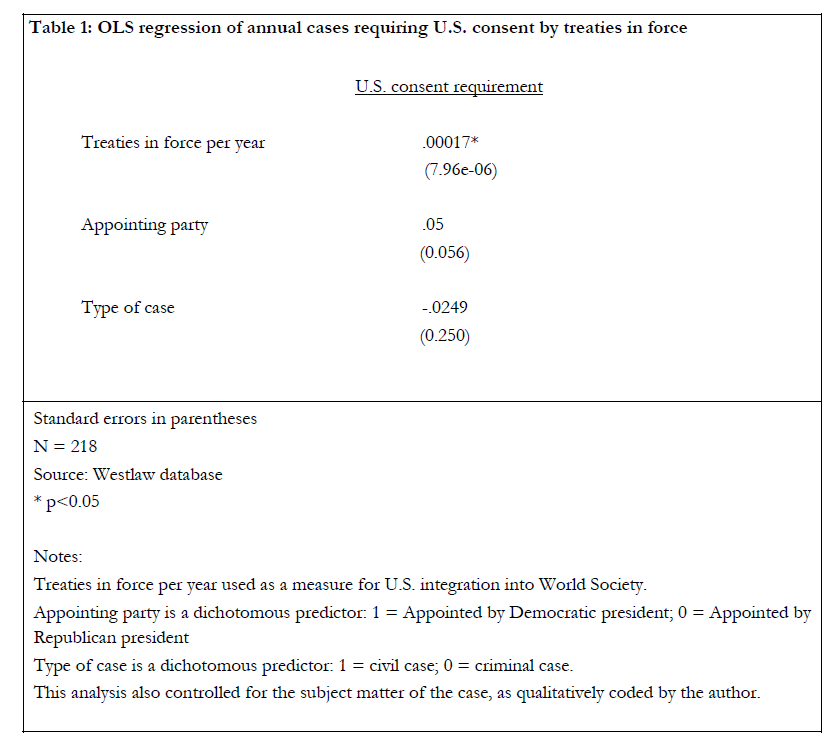

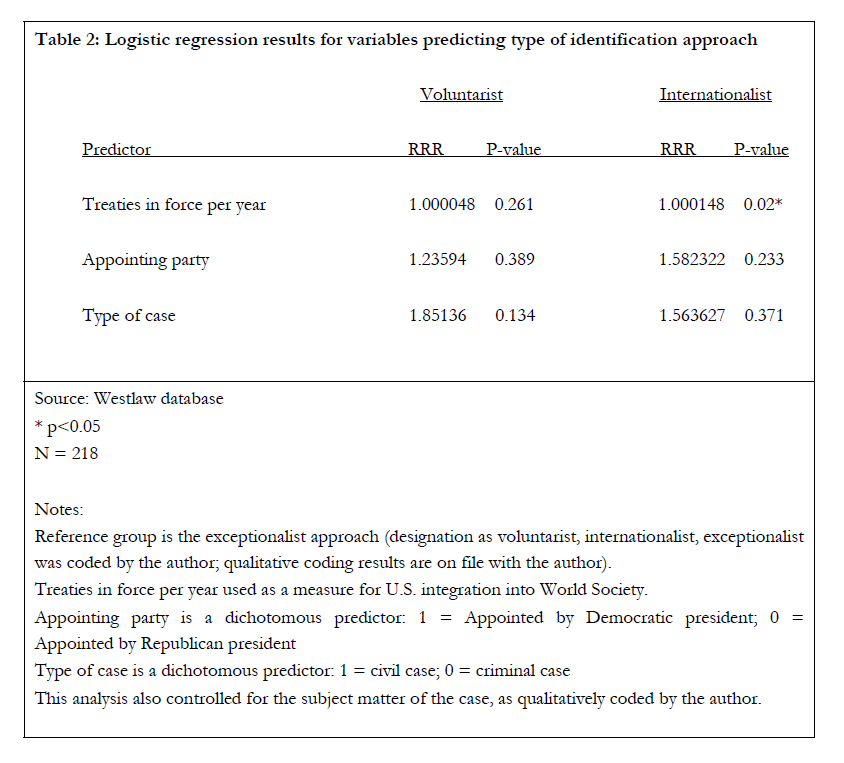

The independent variable of interest is the total number of U.S. treaties and executive agreements in force by year. The annual number of treaties and agreements in force is used as a proxy for the strength of the U.S.’ linkages to world society.105 This independent variable enabled a regression analysis of how variation in identification approaches has changed as U.S. linkages to world society have increased over time. Control variables were also included in the analysis to see if the variation in identification approaches was influenced by the court’s Judicial Circuit, the judge’s appointing party (or the majority party in the case of panels), or the type of case.106

B. Sampling Frame and Biases

Before delving into the statistical analysis, it is important to note a few issues relating to methodology. As with any empirical legal research project, methodological decisions were made at the outset. The most fundamental of those decisions related to the sampling frame, namely the sample of judicial decisions that would be analyzed. For the purposes of this project, an approach known as “universal sampling” best served the analysis. Because of the small number of U.S. cases that engage with questions of identification, it was possible to forego random or quota sampling. While such methods are used often in the social sciences, they are necessary only when the total population to be observed is large and unmanageable. I used the Westlaw database to isolate the available U.S. federal court cases that seek to identify a rule of CIL. It bears mentioning here that an overwhelming majority of case-coding projects use this universal sampling method.

With the sampling method decided, the next key methodological question related to bias. To begin with, the use of the Westlaw database inherently introduces bias as only select federal court decisions are included. This selection bias occurs in two stages. First, West includes decisions that are published in the Federal Supplement. Decisions are published in the Federal Supplement only if they are “of interest” to the general membership of the Federal bar or advance understanding of an area of law. Second, other considerations influence the decisions that get published. For example, all the substantive opinions of certain notable federal district courts, such as the Southern District of New York and the Northern District of Illinois, are included in the Westlaw database. Individual federal judges may also submit particular decisions for consideration by West editors, though short memorandum decisions, orders, and other routine issuances are excluded.107

My content analysis includes only those cases that have been selected for publication in the Westlaw database and, therefore, does not pull from the total universe of U.S. federal court cases. This methodological choice necessarily introduces selection bias. The bias, however, should not affect the generalized institutional trends observed in this Article. It should be the case that trends observed in the analyzed sample are reflective of substantive trends in all U.S. federal cases on this issue.

It is possible that generalized trends related to the identification question—for example, summary dismissal of cases involving CIL—are not captured in the sample examined. This unavoidably introduces some bias. While selection bias is necessarily a limitation of this study—as it is in all empirical studies—based on the nature of the analysis and of West’s selection criteria, it is unlikely that the excluded cases would alter the results. Cases that conform to the approaches examined below may well have been excluded, but their exclusion would only affect the intensity of the variation described below. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that cases that substantively engaged with CIL and departed from the approaches described below would not have been included in the database.108 In other words, the differences between the studied and omitted cases are likely trivial.109

C. Results and Discussion

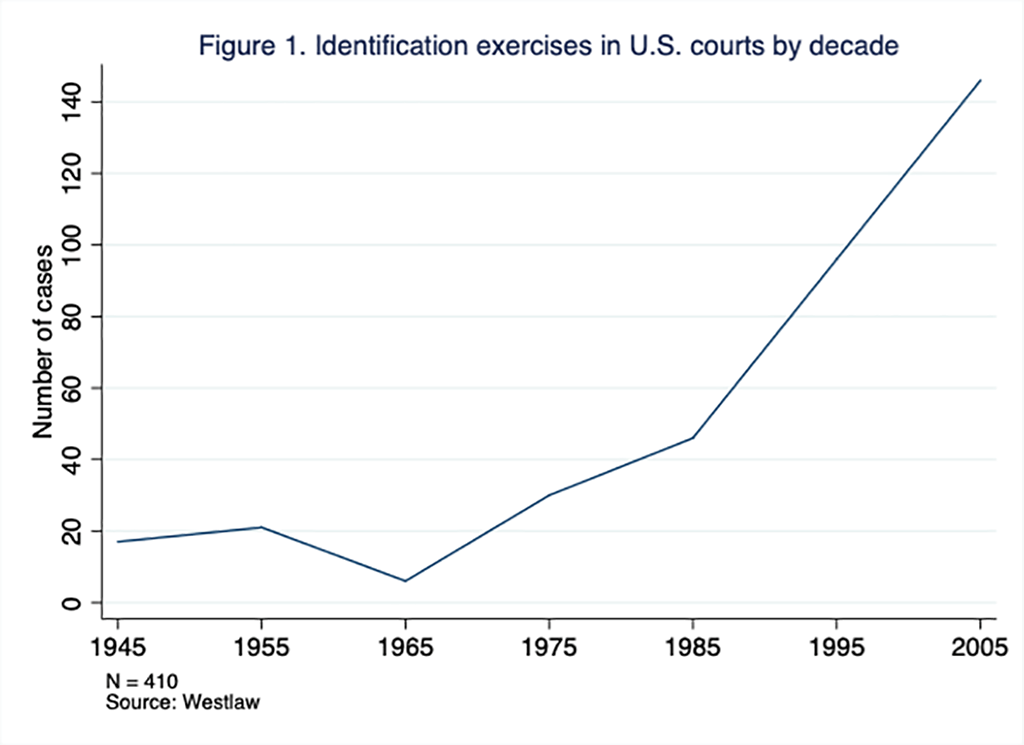

The findings of the qualitative content analysis demonstrate that U.S. integration into the international community is associated with a statistically significant increase in the number of U.S. federal court cases that seek to identify the content or existence of CIL. Consistent with the world society hypothesis, as the number of U.S. treaties in force grew substantially over the latter half the twenty-first century, there was a significant increase in the number of identification exercises in U.S. courts. For example, while between 1945 and 1955 there were only seventeen such cases identified on Westlaw, between 1995 and 2005 there were more than a hundred.

This increase in the number of identification exercises, at least to the sophisticated international law observer, is likely unsurprising. The increased invocation of CIL, on its own, however, does not shed light on whether its usage reflects ceremonial or formal adherence to the international approach. This decoupling question, for the reasons discussed above, is a critical dimension of CIL, which relies on a fluid, internationalized method of inquiry.

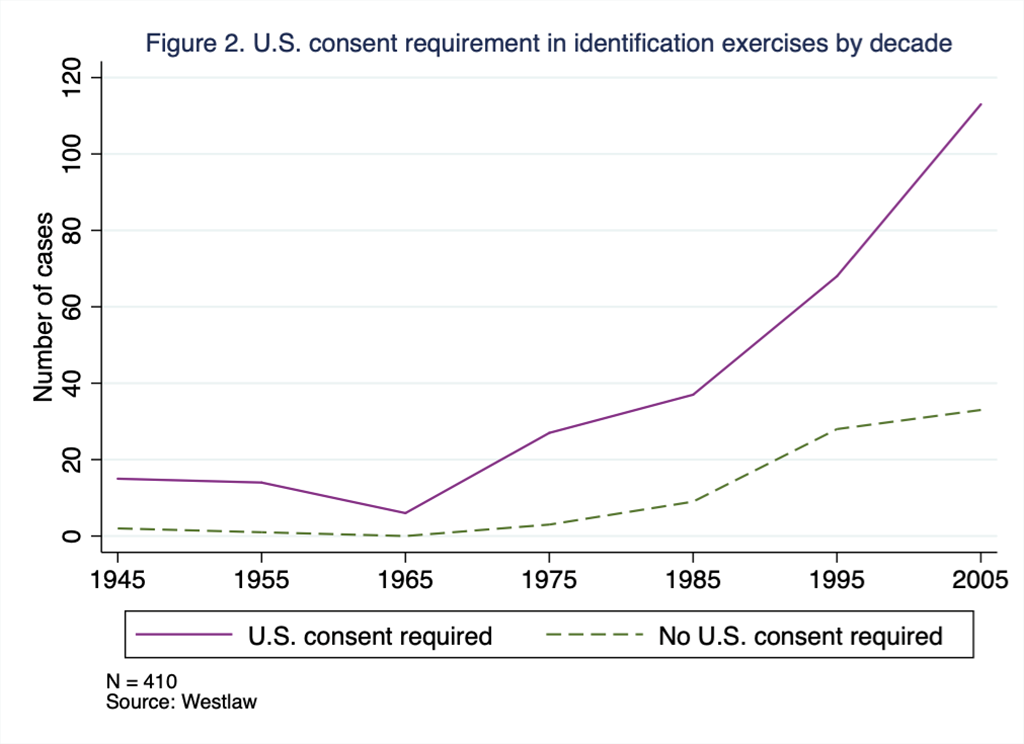

To unpack the decoupling question, further analysis of how the content of international rules were identified by U.S. courts is required. As can be seen from Figure 2 below, the cases revealed that, despite a dramatic increase in identification exercises, important methodological variation persists to this day. While integration into world society is associated with an increased likelihood of resort to the internationalist method,110 identification approaches that stress U.S. consent to the international rule remain the dominant model of identification. 111

Figure 2 reflects that, despite the U.S. integrating into world society, and despite the institutionalization of the internationalist method of identification at the international level (see, supra, Section III), U.S. courts have become increasingly likely to require U.S. consent as an element of determining the existence or content of a customary rule of international law. In other words, in contrast to the two-element approach, the dominant U.S. approach includes a third element. This pattern holds even when controlling for the type of case, the appointing party of the deciding judge(s), and the federal judicial circuit.

The consent element, while critical, still does not tell the full story. The content analysis also revealed that there is variation among the identification exercises requiring U.S. consent. In cases employing the “voluntarist” approach, consent was used as a confirmatory element to supplement the international method of identification. After using international sources and methods to review whether there was a general practice among states that accepted a customary rule as law, the courts in question rely on the consent element as a complementary step to identifying the rule. By contrast, other courts—those employing the “exceptionalist” approach—rely exclusively on U.S. practice or consent to determine the existence of the international rule.

Indeed, for a plurality of U.S. courts, there has been an increasing likelihood of resort to what is, in effect, a hybrid identification method. Rather than simple adherence to an international or national method of identification, the analysis revealed that many courts employ a method that appears to seek legitimacy in both the international and national legal systems.

1. The Internationalist Approach

The internationalist approach refers to the use of the internationally legitimated model to assess the existence of rules of CIL. Courts exhibiting the internationalist approach review relevant international materials, specifically state practice as manifested in treaties, conventions, and treatises, to examine the evidence of the objective and subjective elements of CIL. The institutional friction is resolved by deferral to the expectations and interpretations of the legal personalities and rule-makers of international law, namely the states and organizations of the international community.112 This analysis, in essence, tracks the international method and seeks to ascertain whether international evidence exists to satisfy the identification burden.113

International here denotes a broad, geographically representative examination of state practice to examine the objective and subjective elements of CIL. As articulated by the Second Circuit, this approach “look[s] primarily to the formal lawmaking and official actions of States and only secondarily to the works of scholars as evidence of the established practice of States.”114 Depending on the case and substantive area in question, the reliance on international materials may include international treaties and conventions,115 international organization practice,116 as well as international court decisions,117 domestic court decisions,118 and writings of scholars and jurists.119 The reliance may also be direct or indirect, as in some cases where courts rely on international sources of evidence cited by other U.S. courts120 or international legal experts.121

While adopting the international approach to identify an international rule may appear self-evident, the internationalist approach reflects fundamental, and at times contested, assumptions about the nature and legitimacy of international law, the institutional character of the international legal system, and its operation in U.S. courts. By resorting primarily to international sources of evidence, courts take for granted that the identification exercise is grounded firmly in the consensus norms of the international community.122 Importantly, courts often recognize the primary importance of international sources of evidence irrespective of whether the U.S. has adopted a given norm in its own practice.123 As articulated by the court in United States v. Hasan:

The fact that the United States has not signed or ratified [the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)] does not change the conclusion reached above regarding its binding nature. While the United States’ failure to sign or ratify UNCLOS does bar the application of UNCLOS as treaty law against the United States, it is not dispositive of the question of whether UNCLOS constitutes customary international law, because such a determination relies not only on the practices and customs of the United States, but instead of the entire international community.124

Indeed, as noted above, the Hasan court’s approach to identifying the definition of piracy under CIL comprised a systematic review of international treaties and the judicial decisions of multiple countries, including the U.K., Kenya, and the U.S., as well as scholarly writings.

For courts following the international method, the decoupling is often inverted. They will cite the Supreme Court’s recitation of the international model to legitimize their behavior in the national environment, but actually employ international sources and methods, rather than U.S. precedent or methods, to ascertain the law.125 Courts that transpose the international model but tweak it to make it conform to U.S. context may exhibit what scholars have described as “local rationality within the context of global institutionalism.”126

It is important to emphasize that the internationalist approach does not imply exclusively international sources. Indeed, it often includes consideration of U.S. practice and adherence to the international norm.127 In New Jersey v. Delaware, for example, the Supreme Court looked primarily to the practice of foreign states, as reflected in treatises, to ascertain the existence of an international rule on boundary demarcation in rivers, but also looked to the practice of U.S. states on the issue.128 Similarly, in United States v. Flores, the Court relied in part on evidence of foreign state practice, as elaborated in relevant treatises, to find the existence of an international rule enabling states to assert jurisdiction over foreign vessels disturbing the peace of ports, but also pointed to the invocation of that rule in a prior U.S. case.129 What distinguishes the internationalist approach from the voluntarist approach discussed below is that the internationalist approach employs the international identification methodology without weighted regard for the national internalization of the norm in question. For the purpose of identifying customary rules, U.S. courts adopting the internationalist variant mimic the role of global actors seeking to ascertain the normativity of an international rule by relying upon international sources and evidence.

Grounding the analysis in international sources also reflects socio-legal assumptions about the international legal system, as well as the role of U.S. courts therein. In particular, the internationalist approach reflects key assumptions about the normative source and legitimacy of international legal rules.130 As it pertains to the uncertain terrain of CIL, for courts following the internationalist approach, both methodological and substantive normativity is conceived to arise externally to the U.S. So viewed, answers to questions regarding the normative force of torture prohibitions, for example, arise from the international legal system. That is to say, for the purposes of CIL, courts adopting the internationalist approach operate within a legal system and social context that extends beyond the U.S. The applicable primary and secondary rules, as well as the legitimacy accorded such rules, thus emanate from the international plane.

As elaborated in Section IV, legitimacy as a socio-legal concept is understood by reference to the societal frame of analysis. International law neatly illustrates the contingent, relational character of legitimacy. From the standpoint of the internationalist approach, questions of legitimacy arise on the international plane from the vantage point of states and other international actors. The legitimacy of a rule is a function of the relationship between states and is mediated through the lens of the international legal system. If the international legal system did not play a mediating role, and did not do so effectively, the system could not be normatively coherent. As articulated by the Second Circuit, “[t]he requirement that a rule command the ‘general assent of civilized nations’ to become binding upon them all is a stringent one. Were this not so, the courts of one nation might feel free to impose idiosyncratic legal rules upon others, in the name of applying international law.”131 To ensure the legitimacy of the application of a rule of CIL, then, requires faithful adherence to the internationally agreed approach.

Indeed, those courts adopting the internationalist approach can be understood to be enacting the institutionalized model of the international legal system for identifying CIL. H.L.A. Hart’s conceptual distinction between primary and secondary rules further illuminates the institutional dimension. According to Hart, law may be understood as comprising both primary rules, that is, substantive rules of conduct, as well as secondary rules, which are rules that operationalize the legal system.132 By incorporating the prevailing international methodology, the internationalist approach assumes that international law is a discrete system of law, with its own substantive rules of conduct, as well as its own secondary rules to assess the validity and existence of such rules.133 This recognition also implicitly acknowledges that methodological consistency is critical to the functioning of CIL, and that courts and judges are, as it pertains to the identification of CIL, operating within the international institutional environment.

The internationalist approach may also reflect the notion, which is taken for granted at the international level, that CIL is a dynamic construct, subject to affirmation, contestation, or evolution through the dialogical interaction of national and international actors.134 Judges following this approach are thus accessing and contributing jurisprudence to the fluid development of international legal rules. This approach reflects the dynamic horizontal and vertical integration and interaction characteristic of the international legal system and transnational legal orders.135 The development of CIL, in particular, relies on such recursive transnational information flows.136 As noted by the Supreme Court, the indefinite nature of customary rules accords courts a critical role in this regard: “[i]nternational law, or the law that governs between states, has at times, like the common law within states, a twilight existence during which it is hardly distinguishable from morality or justice, till at length the imprimatur of a court attests its jural quality.”137

Despite the approach of internationalist courts, the legitimacy of international law, particularly when considered by national courts, is a multi-planar issue. The identification and application of CIL in U.S. courts also raises questions of local legitimacy, as mediated by the taken-for-granted logics of the U.S. legal system.138 Such efforts to reconcile the national logics with the plural demands of the international legal system may explain the voluntarist approach to CIL.

2. The Voluntarist Approach

For courts exhibiting the voluntarist approach, the problem of plural institutional environments is resolved by giving weighted deference to the institutionalized methods of the U.S. legal system. Rather than analyzing the practice of states on the basis of a balanced review of international sources—as the cited international method requires—the voluntarist approach ascribes particular weight to U.S. practice with respect to the norm in question.139 After invocation of the international method, the court will typically consult higher U.S. courts to determine if the identification question has previously been answered domestically. And where U.S. practice and international practice broadly align, U.S. adherence to the norm is employed to legitimize the customary rule’s application.140

Courts following the voluntarist approach consider U.S. practice to be elemental to the identification assessment. This added weight accorded to national practice is criticized in international circles for its perceived failure to recognize the rationality of the internationalized rule-formation process.141 By straying from strict consideration of the formal emergence of international rules among international actors on the international plane, according to the ILC and others, national judges fail to respect the separation between the making and adjudication of CIL.142 Alternatively, as viewed through the political lens of foreign and international relations, according additional weight to national practice may be explained as a manifestation of American exceptionalism. What this Article seeks to offer is a contrasting account, grounded in the overlapping social and institutional spheres implicated by identification questions.143

There is a long history of voluntarism in the identification methodology of U.S. courts. As far back as 1796, in Ware v. Hylton, the Supreme Court found that “the relaxation or departure from the strict rights of war to confiscate private debts by the commercial nations of Europe was not binding on the State of Virginia, because founded on custom only, she was at liberty to reject or adopt the custom as she pleased.”144 The Court distinguished customary law from the general law of nations, which is “established by the general consent of mankind, and binds all nations.”145 This distinction also maps onto the long-running, theoretical divide between citizenship and human rights. According to the citizenship conception, rights flow from participation and connection to a discrete society, whereas the human rights framework posits that rights emanate from universalistic (and naturalistic) ideals intrinsic to human nature.146

The modern-day voluntarist approach remains grounded in notions of consent and state enforcement of territorially delimited social protections. Voluntarist courts acknowledge the legitimacy of the international method yet deviate from its instructions in order to ensure the norm’s legitimacy within territorial order of U.S. society.147 In certain cases, courts exhibit voluntarism when seeking to confirm whether a relevant U.S. statute follows the international rule in question. In Siderman de Blake v. Argentina, for example, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit cited a U.S. Court of Appeals decision, the Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States (“the Restatement”), and the legislative history of the U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) to establish that the international rule on valid takings had been adopted by the U.S.148 The court found that the FSIA “reveals a similar understanding of what constitutes a taking in violation of international law.”149

Yet the voluntarist analysis of U.S. practice is not limited to instances where there is formal consent.150 In Amerada Hess v. Argentine Republic, for example, the court first examined international treaties and conventions to identify the customary international right of a neutral ship to free passage on the high seas, before turning to an in-depth treatment of U.S. practice on the subject. The court canvassed additional accords adopted by the U.S. supporting the customary right, as well as judicial decisions, academic writings, and the Restatement, which all recognize and accept the identified norm.151 The court thus adapted the international model to allow for in-depth, weighted consideration of U.S. practice and norms on the question. Similarly, in Sea Shepherd, as part of a multifaceted analysis of the international legal definition of piracy, the court relied on international treaties and treatises to identify general consensus at the international level before looking to whether U.S. jurisprudence agreed with the consensus definition of piracy.152

This modification of the international model to account for U.S. practice and consent has also arisen in cases where the content of CIL is uncertain. In Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Chase Manhattan Bank, the Second Circuit considered the international evidence in light of prevailing U.S. practice to determine whether there exists an affirmative obligation on states to compensate for expropriation under international law.153 The court’s international inquiry focused on the practice of various states, as well as international court judgments, General Assembly resolutions and a variety of American and non-American writings, before turning to a review of U.S. practice.154

While the practice of various other states identified by the Second Circuit favored a range of different standards, including “appropriate compensation” or no compensation, U.S. practice favored full compensation. Faced with “at best a confusing picture as to what the consensus may be as to the responsibilities of an expropriating nation to pay . . . ,” the court modified the inquiry to consider whether international law “never requires an expropriating state to pay more than partial compensation.”155 In other words, rather than relying on its inconclusive international evaluation of whether there is an affirmative duty to always fully or partially compensate, the Second Circuit reframed the issue in the inverse. The court considered whether there is a categorical international rule indicating that full compensation is never required. By reframing the issue in this way, the Second Circuit cleared the ground for application of whatever standard is considered to be fair and just in U.S. courts. While it stopped short of recognizing any particular standard of compensation, the court’s identification exercise, as mediated through the lens of U.S. practice, resulted in a permissive compensation standard.156

The Banco Nacional exercise makes the socio-legal dimension of the voluntarist approach quite plain. Rather than conceiving of the identification exercise as simply a matter of identifying and following an existing international rule, the Second Circuit sought to identify a point of normative convergence. In doing so, the court adapted the international model, conditioned its analysis on the basis of prevailing U.S. practice, and applied a norm that ostensibly could be reconciled with the institutional logics of both legal systems.

A consistent contemporary manifestation of the voluntarist approach has also arisen in Alien Tort Statute (ATS) cases. Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, courts have considered whether a norm is universally recognized under the law of nations, and whether it is “sufficiently definite to support a cause of action” under the federal common law.157 Though application of the ATS presents a number of considerations specific to U.S. law,158 the predicate question of whether a norm is universally recognized is an identification question, and U.S. recognition of the norm has on numerous occasions played a primary role.159

Take the example of Roe v. Bridgestone Corp.160 To ascertain whether there was an international law prohibition on forced labor, the court concluded that “[i]t would be odd indeed if a U.S. court were to treat as universal and binding in other nations an international convention that the U.S. government has declined to ratify itself.”161 There was no dispute that the U.S. had not ratified International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 29 and its definition of forced labor. But the plaintiffs argued that the U.S. later bound itself to Convention 29 by the ILO’s adoption of the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.162 The court did not analyze whether those sources reflected a general practice of states accepting a definition of forced labor as law. Rather, the lynchpin of the argument was that the U.S. had not accepted the norm.163

The district court in Abdullahi v. Pfizer took a similar approach.164 To evaluate whether there existed an international rule proscribing medical experimentation, the court relied on U.S. practice. The court first pointed to the fact that the U.S. had not ratified the international standards governing biomedical research known as the Nuremberg Code.165 Then, the court indicated that the Nuremberg Code “has not been adopted by the international community.”166 In this way the Abdullahi court, like the other courts following the voluntarist approach, afforded considerable weight to U.S. practice in assessing whether there exists international consensus.167

U.S. courts’ subsidiary reliance on the Restatement, a treatise written by the American Law Institute (ALI), may also reflect a voluntarist approach. On many occasions, support for a customary international rule is grounded in the Restatement.168 This may of course reflect considerations of expedience as it may not be practicable for courts to revisit an identification analysis previously undertaken by the ALI. In certain instances, the Restatement authors have already conducted an extensive examination of international evidence. Moreover, federal judges are often not as well-versed in international law as the contributors to the Restatement.169

Nevertheless, in discussing reliance on the Restatement, it should also be recalled why the ILC cautions against reliance on scholarly writings and the products of collective bodies such as the ALI: such writings may reflect the national or individual positions of the authors.170 The Restatement acknowledges that it sets out to restate the foreign relations law of the U. S., that is, international law viewed as applicable to the U.S. rather than by the international community.171 Accordingly, courts that rely on the Restatement and the foreign relations law of the U.S. as a subsidiary, yet required, precondition to the rule’s legitimacy, would appear to take for granted that voluntary acceptance of the customary rule by the U.S. legal community is fundamental to the identification analysis.

Viewed through a sociological lens, this practice of according weight to U.S. acceptance of a rule may describe a process of localization or translation. The localization of global norms is a process of assessing the global to ensure congruence with the local.172 That is, the legitimacy of a global rule is mediated through established local norms.173 In effect, U.S. courts following the voluntarist approach are organizations trying to be “multiple things to multiple people.”174 In identifying a customary rule, voluntarist courts reveal the contested identity of operating within multiple normative environments and legal discourses. Although the nationally derived identity prevails, the international model’s translation into the U.S. environment still exhibits the constitutive effect of both institutions.

Of course, as will be discussed further below, in certain instances the adaptation or rejection of the international approach may reflect a prevailing uneasiness with normative universalisms,175 a conscious misuse of the applicable rules, or a misunderstanding of the international approach. And proponents of the positivism and universalism of international law would likely lament such an account as apologist or unduly relativist. Yet, the normativity of the voluntarist approach is not at issue here. Instead, its place in this typology is merely developed as a socio-legal alternative to the traditional explanations of national divergence grounded in ignorance, inexperience, or exceptionalism.176 When viewed in the light of institutional theory, translation of the international model emerges as a rationalized method of maintaining legitimacy in a pluralistic environment.177

3. The Exceptionalist Approach

The exceptionalist approach bypasses the international approach in favor of national doctrines and logics. Most notably, this approach generally foregoes international sources in favor of U.S. foreign relations law. Although it is outside the scope of this analysis to speculate as to any ideological underpinnings of this approach,178 it merits attention here because of its subtle, but important, contrast with the voluntarist approach. Rather than requiring U.S. acceptance of an internationally agreed rule, the exceptionalist approach evaluates a rule primarily on the basis of U.S. practice without even ceremonial consideration of the two-element, international test.

Perhaps the most explicit and consistent example of this approach is in cases addressing jurisdictional questions. In Hasan, for example, the court relied primarily on the Restatement to assert that, “under international law principles,” there exists a so-called “protective principle” of extraterritorial jurisdiction.179 In United States v. Robinson, the court relied only on the Restatement and U.S. cases to examine the “protective principle.”180 And in United States v. Marino-Garcia, the court first employed an internationalist approach—citing to international conventions and the works of jurists—to find that states assert jurisdiction over stateless vessels, before relying exclusively on U.S. cases and the Restatement to support the existence of the protective theory of extraterritorial jurisdiction.181 Courts have resolved other extraterritorial jurisdiction questions by exclusive resort to the Restatement and U.S. practice.182

Section 402(3) of the Restatement indicates that states have the competence to regulate “certain conduct outside its territory by persons not its nationals that is directed against the security of the state or against a limited class of other state interests.”183 Indeed, the Restatement suggests “an expansive state capacity to legislate extraterritorial conduct that threatens national security,” and several states have codified provisions that follow the general protective rubric reflected in Section 402(3).184 Yet, despite some acceptance, the prevailing view at the international level is that the Restatement’s interpretation of protective jurisdiction does not reflect a rule of CIL.185 Such primary reliance on the Restatement, thus, wittingly or unwittingly, identifies a rule that would likely not satisfy the two-element approach.

The primary reliance on U.S. practice and the Restatement also extends to other areas of law. For example, in Kadic v. Karadzic, to assess whether the plaintiffs had asserted international law violations, the court first had to consider whether the “Bosnian-Serb” entity headed by Radovan Karadzic in the Balkan conflict of the 1990s met the definition of a state, and it did so by relying exclusively on Section 201 of the Restatement.186 The Restatement incorporates the criteria for recognition of statehood set forth in the treaty known as the Montevideo Convention, yet those criteria remain contested as a matter of CIL.187 Even if the Montevideo criteria—and thereby the Restatement’s definition—reflect CIL, the Karadzic court’s analysis and language remain telling. The court speaks in terms of “the Restatement’s definition of statehood” rather than the definition of statehood under international law, and cites exclusively to the Restatement to support additional rules of CIL.188 The court also relied heavily on U.S. jurisprudence, noting that “[o]ur courts have regularly given effect to the ‘state’ action of unrecognized states.”189 In totality, the Karadzic court’s assessment reflects an evaluation of the U.S.’s posture vis-à-vis the implicated identification questions, rather than acceptance of those rules generally at the international level.

As noted previously, it may be that U.S. courts rely on the Restatement and other domestic sources for ease of reference or out of ignorance. Courts may not have the resources or know-how to assess international sources, and the authors of the Restatement have often conducted voluminous research into the identification questions raised. Yet, even if courts are merely resource-constrained and reliance on the Restatement is motivated by practical efficiency, that assessment should signal as much—in other words, that the Restatement’s rule is reflective of international law on the question. Without such an international tie-in, the exercise remains conspicuously disengaged from legitimate accounts produced at the international level.190 The Restatement, as a treatise on U.S. foreign relations law, is not viewed within the international legal system as an authoritative restatement of CIL.191 Moreover, the Restatement was published in 1987, long before many of the identification questions arose.

Primary or exclusive reliance on U.S. sources also arises from adherence to the doctrine of stare decisis. This variant of the exceptionalist approach further reveals the socio-legal dimension of identification questions, particularly where the questions have been previously addressed by other federal courts, especially higher courts of appeal. Precedent is the foundational institutional logic of U.S. courts and the common law, and it serves to order the operation of the U.S. legal system by stabilizing settled points of law.192 Yet, the doctrine of precedent is fundamentally at odds with the nature of CIL. As noted above, customary rules are necessarily fluid and dynamic, shifting and evolving in accordance with the practice and acceptance of States. Even where customary rules are well settled, the institutionalized model followed by international legal actors is to seek confirmation from international rather than national sources.

Despite this apparent contradiction in institutional imperatives, U.S. courts routinely rely exclusively on precedent to identify CIL.193 Notably, some courts have explicitly rejected the international method in favor of the controlling decisions of U.S. appellate courts. For example, in Ali Shafi v. Palestinian Authority, the district court found that

[a] court may look to “the customs and usages of civilized nations; and as evidence of these, to the works of jurists and commentators, who by years of labor, research and commentators, have made themselves peculiarly well acquainted with the subjects of which they treat[,]” but only when there is “no controlling . . . judicial decision” on that particular subject.194

The court continued by noting that “[D.C. Circuit] precedents are binding here, whether or not they reflect an antiquated construction of international norms.”195

This deference to higher courts also extends to the process of determining the content of rules of CIL. Some district courts rely on circuit court guidance on how to approach identification questions. In Estate of Rodriguez v. Drummond Co., for example, the district court relied on the “process of ascertaining customary international law” delineated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.196 Similar deference has been shown to the approach of the Second and Third Circuits, among others.197 Leaving aside the temporal issues associated with deference to prior appellate decisions,198 the legitimacy assumptions are plain. Rather than resort to the international method, courts exhibiting the exceptionalist approach explicitly or implicitly favor the institutional logics of the U.S. court system. The courts feel constrained by the hierarchical demands institutionalized within the U.S juridical field,199 and proceed as strictly national actors in a legal system where organizational legitimacy is grounded in the consistency, efficiency, and fairness of precedent.200

VI. Conclusion

The foregoing empirical analysis of U.S. federal court decisions reveals that more fine-grained consideration is required to understand how competing international and national models shape processes of rule identification. While extant international legal studies focus largely on transnational processes of norm replacement, or recursive interaction between the national and international levels, sociological institutionalism offers a rich theoretical toolkit for unpacking how plural institutional logics interact to shape behavior at the national and sub-national levels.

Despite accelerating U.S. integration into world society following World War II, federal judges have become increasingly likely to depart from the international approach to identifying rules of CIL. In contrast to the globally institutionalized two-element approach, U.S. courts have become more likely over time to require a third element, namely U.S. consent. Yet, what emerges from this study is that, rather than outright rejection of the international model in favor of U.S. consent, federal judges often hybridize the approach to identification to maintain legitimacy nationally and internationally. That U.S. courts across circuits are increasingly likely to resort to a hybrid approach has significant implications for the coherence and stability of international law, as well as its legitimacy and salience in the U.S.

Building from this study, further research is needed to determine whether the pattern of legal hybridization identified in U.S. federal cases holds across organizational forms, including among administrative agencies and corporations subject to competing norms. Additional case studies would enable broader insights as to the circumstances under which vested national models are subject to hybridization as organizations seek legitimacy in both the international and national domains. By going beyond theories of adoption or replacement, such studies would offer further insight as to the social circumstances under which international models shape national decision-making and organizational change.

a) Appendix 1

b) Appendix 2

- 1Statute of the International Court of Justice art. 38(1)(b), June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, 33 U.N.T.S. 993.

- 2Int’l Law Comm’n, Rep. on the Work of Its Sixty-Seventh Session, U.N. Doc. A/70/10, at 32–42 (2015).

- 3Int’l Law Comm’n, Rep. on the Work of Its Sixty-Third Session, U.N. Doc. A/66/10, at 305 (2011) [hereinafter U.N. Doc A/66/10] (“There are differing approaches to the formation and identification of customary international law. Yet an appreciation of the process of its formation and identification is essential for all those who have to apply the rules of international law. Securing a common understanding of the process could be of considerable practical importance. This is so not least because questions of customary international law increasingly fall to be dealt with by those who may not be international law specialists, such as those working in the domestic courts of many countries, those in government ministries other than Ministries for Foreign Affairs, and those working for non-governmental organizations.”).

- 4See, for example, Hersch Lauterpacht, The Function of Law in the International Community 3 (2011) (describing the positivist conception of international law).

- 5Phenomenology refers to the structures and models of consciousness and behavior that shape the decisions and arguments of individuals. It is to be distinguished from ontology, which considers decisions and arguments to be driven purely by analysis and rationality. See Phenomenology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Dec. 16, 2013), http://perma.cc/9G7V-P6RW. For an additional citation on phenomenology versus ontology, see John Meyer, Reflections on Institutional Theory and World Society, in World Society: The Writings of John Meyer 36, 46–47 (Goerg Krucken & Gili Drori eds., 2009) [hereinafter World Society].

- 6See generally Patricia Bromley & John W. Meyer, Hyper-Organization: Global Organizational Expansion (2015).

- 7See generally John W. Meyer & Brian Rowan, Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony, 83 Am. J. Soc. 340 (1977) (describing organizational institutionalism).