The Global Rise of International Commercial Courts: Typology and Power Dynamics

Over the past decade, there has been a proliferation of International Commercial Courts (ICCs) across the globe. ICCs are specialized tribunals within the domestic court hierarchy tailored for the adjudication of complicated cross-border commercial disputes. Most ICCs share similar features, such as a set of flexible procedural rules comparable to those in international arbitration, multilingual court proceedings, and the recruitment of overseas judges or foreign legal experts.

The global phenomenon calls for a systematic comparative study of the different generations of ICCs and their power dynamics. This Article will offer a unique typological framework to study the evolution of ICCs. In particular, emphasis will be placed on the power dynamics among the ICCs such as horizontal power dynamics among the ICCs inter se, and diagonal power dynamics between the ICCs and international arbitration. This Article argues that the most apt characterization of the two dimensions of power dynamics is “co-opetition,” a combination of “cooperation/collaboration/complementarity” and “competition.” While a race for cases and foreign litigants is inevitable, we argue that there is significant room for inter-regional cooperation and coordination to allow for and capitalize on different ICC niches and specialties.

Table of Contents

III. Three Generations of ICCs

A. ICCs 1.0: Established Jurisdictions

1. London Commercial Court (LCC)

2. The Commercial Division of the New York Supreme Court (NYCD)

B. ICCs 2.0: Emerging Jurisdictions

2. Astana International Financial Centre Court in Kazakhstan (AIFC)

3. Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC)

C. ICCs 3.0: Regional and Geopolitical-Economic ICCs

2. China International Commercial Court (CICC)

A. The Concept of “Co-Opetition”

I. Introduction

Over the past decade, there has been a proliferation of International Commercial Courts (ICCs) across the globe.[1] ICCs are specialized tribunals within the domestic court hierarchy tailored for the adjudication of complicated cross‑border commercial disputes. Most ICCs share similar features, including a set of flexible procedural rules comparable to those used in international arbitration, multilingual court proceedings, and the recruitment of overseas judges or foreign legal experts. As will be seen, the comparable features can be primarily explained by two reasons: (i) arbitralization of the judiciaries and (ii) the demand for competitive and user‑friendly service offerings provided by these specialized courts. We shall delve into these two reasons in detail in the sections below.

The rapid global rise of ICCs is striking and stands as a game-changer in the arena of international dispute resolution institutions. It fundamentally reshapes the landscape of international legal adjudication by disrupting the traditional dichotomy between international litigation and arbitration as mutually exclusive dispute resolution service providers, and by challenging the conventional advantage of international arbitration in handling cross-border commercial disputes. According to the 2018 International Arbitration Survey, the major benefits of international arbitration are the enforceability of awards under the New York Convention, the ability to avoid national courts and local legal systems, and flexibility.[2] Most recently, ICCs have mushroomed in the regions alongside the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) such as China and Kazakhstan, as well as in the post-Brexit European Continent.[3] The top-down approach in the establishment of ICCs in the jurisdictions of these regions also reflects their geopolitical aspirations to rise as legal hubs and important international commercial law centers.

The global phenomenon calls for a systematic comparative study of the different types and features of ICCs and their power dynamics. In this respect, there has been a growing literature on the study of ICCs that focuses on their: (i) socio-historical origins,[4] (ii) international functions and utility,[5] and (iii) establishment.[6] However, there is a significant literature gap in the sense that the existing literature fails to take into account the dynamic interaction between ICCs and between ICCs and international arbitration. As a result of this gap, the literature underestimates the rising global proliferation and influence of ICCs and carries a presupposition of the dominant role of arbitration in international adjudication. In other words, ICCs—which form an indispensable part of international adjudication and global dispute resolution—are being underestimated by policy makers and legal scholars alike. This Article serves as a reality check and a timely reminder that ICCs, and their related governance and legitimacy issues, need to be attended to in order to depict a full picture of global adjudication in the twenty‑first century.

In addition to building upon existing scholarship, this Article will offer a unique typological framework to study the global rise of ICCs. In particular, this Article will emphasize the power dynamics among the global ICCs, such as horizontal power dynamics among the ICCs inter se and diagonal power dynamics between the ICCs and international arbitration. This Article argues that the most apt characterization of the two dimensions of power dynamics is one of “co‑opetition,” a combination of “cooperation/collaboration/complementarity” and “competition,” a notion borrowed from the study of International Financial Centres (IFCs) and New Legal Hubs (NLHs).[7] While a race for cases and foreign litigants is inevitable, we argue that there is significant room for inter‑regional cooperation and coordination to allow for and capitalize on different ICC niches and specialties.

This Article proceeds as follows. Section II studies the global rise of the ICCs and creates a new typology to classify different ICCs worldwide. In doing so, we propose a new typology that takes into account ICCs’ socio-historical origins, the process of their establishment, jurisdictional coverage, and, most importantly, the politico‑economic incentives behind their establishment. This Article then groups them into three generations: ICCs 1.0, ICCs 2.0, and ICCs 3.0. Section III then conducts a systematic and in-depth comparative study of the three types/generations of the global ICCs. Section IV examines the power dynamics associated with the existing ICCs. The issue of “competition” or “cooperation/collaboration/complementarity” can be viewed both horizontally and diagonally. The horizontal view concerns the power dynamics among the three generations of ICCs inter se. The diagonal view of the global rise of ICCs highlights the relationship between transnational litigation and international arbitration. Conventional discourse often refers to the two as opposite and competing service providers engaged in a “race to the top” in the adjudication business.[8] Section V concludes that the “arbitralization” of judiciaries as a new trend of the transnational legal order has emerged and is evident in the ICC evolution. A majority of ICCs have incorporated elements of arbitration and Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) elements into their court procedures to attract adjudication business. Although it is difficult to estimate the precise impact of ICCs on the transnational legal order given that many have been established only recently, the issues of governance, legitimacy, and norm-creation by ICCs will have far-reaching impacts in international law.

II. Typology

A. Global Picture

Typology is defined as the “ordering of entities into groups of classes on the basis of their similarity.”[9] The approach is to “minimize within-group variance” such that each group internally is as “homogeneous as possible.”[10]

The typology of ICCs can be established in accordance with the following non-exhaustive list of independent variables: (i) establishment history, (ii) establishment region/jurisdiction, (iii) legal origin (common law/civil law), (iv) court infrastructure, (v) judge capacity-building and recruitment of foreign judicial/legal expertise, (vi) procedural design (including language of proceedings), (vii) governing law, and (viii) caseload.[11] We start by providing an overview of the global picture of the existing ICCs.

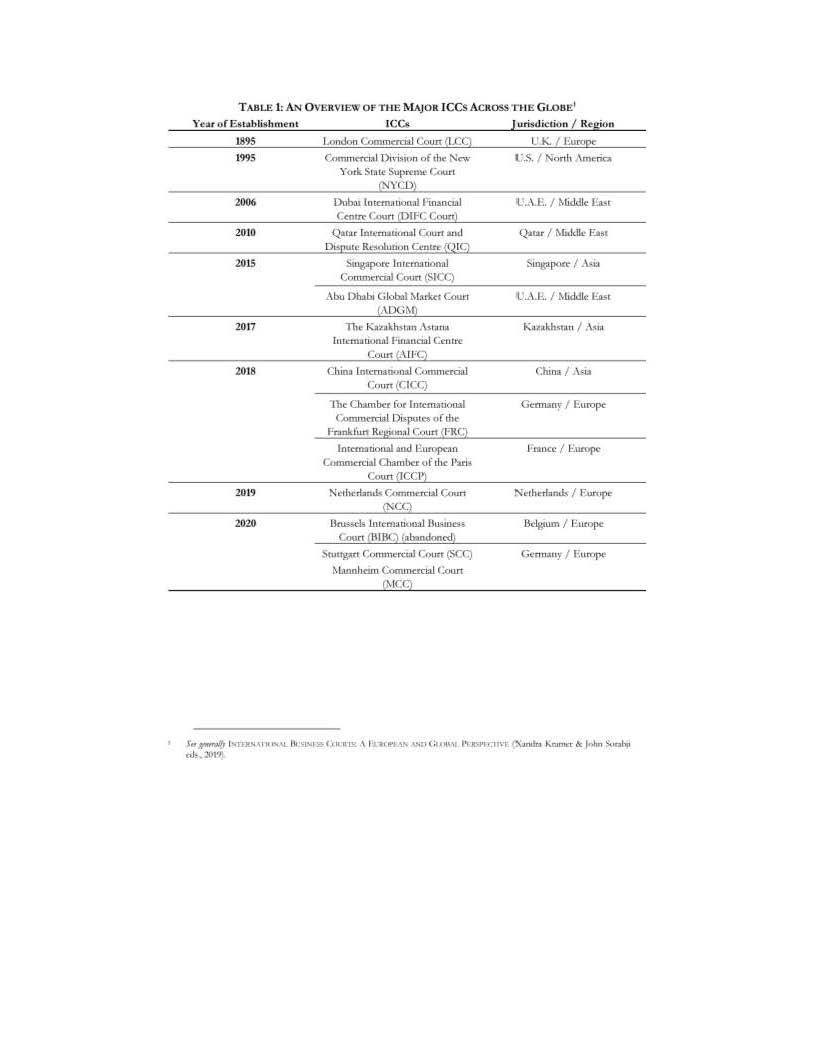

Currently, there are thirteen major or significant ICCs established around the world.[12] This number does not include the Brussels International Business Court (BIBC), which was proposed in 2020 but abandoned in 2021, as discussed in Section III. An overview of the geographical distribution and the year of establishment of the thirteen ICCs is illustrated in Table 1 below.

As shown in the table above, there has been a global emergence of ICCs over the past decade, with eleven new additions since 2010. Regarding their geographical distribution, ICCs are scattered across the globe, including in Europe, North America, the Middle East, and Asia.

The emergence of ICCs worldwide has prompted scholars to look into the relationship between ICCs and international arbitration.[13] The orthodox account assumes a competition for forum selection clauses in commercial contracts, creating a race-to-the-top drive for optimizing procedural rules and efficiency.[14] In 2015, a report published by the U.K. Ministry of Justice implied the competition view by noting the “increasing competition in the international dispute resolution market with other jurisdictions marketing themselves to attract disputes traditionally adjudicated in London.”[15] The 2015 U.K. Ministry of Justice Report aims to understand what drives litigants to initiate commercial litigation and choose particular fora for their litigation.[16]

Upon closer examination, ICCs are region-centric niche courts equipped with optimized procedural rules with specific geopolitical focuses. Rather than treating ICCs and international arbitration as “competitors” or “substitutes” within a unified supply market,[17] this Article argues that each ICC offers “complementary” services specifically catered for their target businesses in different markets. This “complementary view” will become apparent following our global survey of ICCs in Section II below.

B. Various Approaches

In order to systematically analyze the global rise of ICCs, this Article creates a new typology for categorizing them worldwide by building on existing scholarship in the field. In the following paragraphs, we present our original typology, which contributes to the scholarly understanding of the power dynamics of ICCs.

One school of scholarship has focused on the degree to which individual ICCs are affiliated with the English legal system and, hence, has categorized ICCs as (i) “traditional,” (ii) “transplant,” or (iii) “hybrid.”18 This categorization has focused on the extent to which an ICC incorporates the features of a traditional English court. In a way, this typology could be traced back to the legal origins theory proposed by Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer (“LLS”) in the World Bank Doing Business initiative.[18] In the LLS legal origins school, the central claim is that the English common law system is generally hospitable for advanced financial markets and is conducive to economic development.[19] Similarly, there have been attempts to evaluate the new ICCs by benchmarking them against the London Commercial Court (LCC) in London and the English legal system, which has dominated the ICC market for a long period of time.[20] ICCs were essentially divided into either benchmark common law ICCs (the LCC in the U.K.), or various “runner-up” ICCs, including the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC) in Singapore and the Dubai International Financial Centre Court (DIFC Court) and Qatar International Court and Dispute Resolution Centre (QIC) in the Middle East.[21] Based on this school of thought, the “transplant” and “hybrid” ICCs naturally flow from the common law. As such, a “traditional” ICC would use the common law system and the English language in the ICC while maintaining the domestic legal system. A “transplant” ICC would introduce some common law features in ICC proceedings but with its own modifications, such as the use of its own language.[22] A “hybrid” ICC, on the other hand, would include features of arbitration in addition to the traditional court rules. While this method of categorization can capture some features of different ICCs in the world, particularly their resemblance to the LCC, it fails to discern the deeper differences between ICCs. It follows that this categorization may become an Anglo-centric model for the purpose of comparison. For instance, the ICCs in the U.K. and Singapore both adopt the common law system and the English language directly and are thus “traditional” ICCs. However, there are significant differences between the two, as the subsequent analyses show. For example, the SICC uses International Judges, whereas the LCC consists solely of domestic English judges. Moreover, the LLS school excludes the Commercial Division of the New York State Supreme Court (NYCD) in the U.S. and the recently established China International Commercial Court (CICC) in China from its typology.

Another school of scholarship was coined by Pamela Bookman, under which ICCs are split into three categories: (i) “old-school international commercial courts” such as the LCC and the NYCD; (ii) “investment-minded courts” such as the QIC and the DIFC Court in the Middle East; and (iii) “aspiring legal hubs,” which are subdivided into the SICC and the European Courts.[23] Bookman’s typology is distinguished from the legal origins approach because it takes into account the economic and political motivations which underlie the establishment of ICCs. Under this categorization, the CICC established by China was separately discussed and was not included within any of the above categories. While this typology has the benefit of considering the underlying motivations of various ICCs, the scope of “legal hubs” (category (iii)) is vaguely defined. Arguably, the QIC and the DIFC Court can also be categorized as aspiring legal hubs, given their status as jurisdictional carve-outs in the U.A.E. This unique status surmounts the pre-existing legal restraints in the Middle East Islamic law that may not be favorable to trade and commerce (for example, the legal prohibition against riba (interest charged on loans)).[24] Moreover, such classification ultimately boils down to the question of what qualifies a legal hub, which is an elusive concept largely driven by the state’s marketing or image work.

Zhang adopted a different approach by classifying ICCs in accordance with the legislative arrangements that empowered their establishment.[25] The first category consists of the SICC and the Kazakhstan Astana International Financial Centre Court (AIFC Court), which were established via constitutional amendments.[26] The second category consists of ICCs in Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium (the latter of which the proposed court has been abandoned, see Section III below), which were established via amendments to the host states’ domestic laws. These courts are situated within their respective domestic legal systems. The third category comprises the CICC, the DIFC Court, the QIC, and the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Court. The third category is an intermediate category, as these courts have their own independent legal and regulatory framework (as in the second category) but were not established by constitutional amendment.

Drawing from the above literature, we distinguish this Article from the existing scholarship and propose a new typology for classifying different ICCs worldwide. First, as observed by Tom Ginsburg, the missing key word in the analysis of legal institutions in economic development is “politics.”[27] In his article, Ginsburg revisits the relationship between law and economics, observing the tension between the traditional assumption of the centrality of formal, rational law and the empirical evidence in Asia.[28] As observed in the Law and Development Movement, the causal relationship between law, development, and politics is multidirectional.[29] Max Weber and Douglass North proposed a neoclassical or “New Institutional Economics” (NIE) model of causation between law and development, concluding that a formal, rational legal system is a necessary condition for economic development.[30] Such a causal link is severely challenged, however. A close examination of the empirical experience in East Asian economies would reveal that a robust legal system may not be a necessary condition for economic growth.[31] Expanding on Ginsburg’s conclusion, we submit that the underlying geopolitical and economic motivations behind the emergence of international legal infrastructure should be the primary focus of ICC typology.

Given the above premises, we propose that the new typology shall take into account three main factors: (i) the evolution (in other words, establishment history and geographical location) of ICCs; (ii) the politico‑economic motives behind the establishment of ICCs; and (iii) the newer features of ICCs that make them as welcoming and effective as international arbitration. Inspired by Menkel‑Meadow’s work on the evolution of dispute resolution,[32] ICCs are classified into three generations: (i) ICCs 1.0, which includes ICCs in “established jurisdictions;” (ii) ICCs 2.0, which largely cover ICCs in “emerging jurisdictions;” and (iii) ICCs 3.0, which consist of those ICCs with geopolitical-economic motivations. This model of typology, which highlights the waves of ICC evolution, is based on scholarship by Janet Walker,[33] Gary Bell,[34] and Matthew Erie,[35] who approached ICCs by their socio-historical origins and legal origins. It also builds on the work of Pamela Bookman,[36] Stephan Wilske,[37] and Sheng Zhang,[38] who examined ICCs by looking into the underlying motives driving their establishment to assess their specific geopolitical and economic considerations.

This Article presents a novel and unique typology, which clarifies and aids scholarly understanding of the power dynamics of ICCs—namely, a three‑generation typology of ICCs.

The first generation of ICCs is grouped as ICCs 1.0, which refers to those traditional ICC giants in “established jurisdictions.” These jurisdictions are global dispute resolution fora seeking to maintain their dominance in the transnational litigation market. The LCC in London and NYCD in New York are long‑established, well-recognized, and world-renowned ICCs with a high volume of international cases and high-quality judgments that are cited around the world.[39]

ICCs 2.0 alludes to the second wave/generation of ICCs established in “emerging jurisdictions,” which aim to enter the adjudication business market, often with a specific geographical focus. Examples of the ICCs in this group include the SICC in Singapore; the DIFC Court, QIC, and ADGM Court in the Middle East; and the AIFC in Kazakhstan.

Third-generation ICCs, which are grouped as ICCs 3.0, are characterized by their strong politico-economic motivations. This category refers to specialized commercial courts triggered by specific politico-economic incidents and aims. They can be broadly sub-categorized into (i) post-Brexit European courts[40] and (ii) the Belt and Road Court—specifically, the CICC established by China.

Moreover, we observe that ICCs have all evolved to become more comparable to international arbitration. ICCs are increasingly “arbitralized” by allowing ICCs to assume jurisdiction over disputes without any link to the home country of the ICC (as is the case in the SICC).[41] Many ICCs also allow judges with foreign and international law expertise to sit on the bench,[42] which parallels the ability to pick arbitrators with specific expertise. The ICCs 2.0 and 3.0 have significantly enhanced their competitive edge by setting themselves up to attract the widest range of disputes possible.

It is noteworthy that the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (HKCFA) has been classified as an ICC in work by Matthew Erie and Janet Walker.[43] This may be attributed to the fact that these articles classifying the HKCFA as an ICC focused on the “New Legal Hubs” (as in Erie’s analysis) or “specialized commercial courts” (as in Walker’s analysis) rather than ICCs per se.[44] While the HKCFA consists of an international bench with non-permanent judges from overseas common law jurisdictions, for present purposes, the HKCFA is not included as an ICC for two reasons. First, it is not a specialized court or division solely dedicated to the adjudication of commercial cases with an international nature. The HKCFA, apart from commercial cases, also hears criminal, constitutional, and administrative cases. This is distinguished from specialized ICCs such as the SICC in Singapore, which is a division of the Singapore High Court (subordinate to the Court of Appeal) and only hears international commercial cases.[45] Second, the HKCFA does not act as a court of first instance. As entrenched in Article 82 of the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (the Basic Law), the HKCFA is the final appellate court vested with the power of final adjudication.[46] This contrasts with the SICC, which takes on first-instance cases either from parties’ agreement, by virtue of their jurisdictional clause, or by case transfers from the Singapore High Court.[47] The key difference is that the HKCFA is not subject to further appeals. In contrast, a judgment from the SICC is subject to appeals to the Court of Appeal of the Singapore Supreme Court.

III. Three Generations of ICCs

Before delving into the analyses of the global ICCs 1.0 to 3.0, for purposes of the comparative study, we list various features of the ICC landscape that allow for a comparison of the efficacy of the various ICCs. These features include establishment history, region/jurisdiction, legal origin (common law/civil law), court infrastructure, judges (number, domestic, foreign), procedural design, governing law, and caseload distribution.

A. ICCs 1.0: Established Jurisdictions

Both the U.K. (London) and the U.S. (New York) are well-regarded as traditional and established common law jurisdictions. ICCs in both jurisdictions are, in fact, separate domestic courts or divisions within their ordinary judicial systems.

1. London Commercial Court (LCC)

The LCC was established in 1895 as a subdivision of the Queen’s Bench Division of the English Court, one of the three divisions of the English High Court, alongside the Chancery Division and the Family Division.[48] Within the Queen’s Bench Division, there are specialist courts, including the Administrative Court (which hears applications for judicial reviews), the Business and Property Court, and the Technology and Construction Court.[49] Since 2017, the LCC has been incorporated as part of the Business and Property Court, with a “Financial List” dedicated to high‑value complex commercial cases.[50] The LCC, currently consisting of thirteen English judges who are empowered to sit for both the Admiralty Court and the Commercial Court, hears all commercial disputes and acts as a supervisory court for international arbitration.[51] The LCC primarily accepts cases if the parties agree to submit to the jurisdiction of the English courts by a choice of forum clause.[52] Other bases of jurisdiction include: (i) the defendant being domiciled in England; and (ii) for claims with multiple defendants, one defendant being an “anchor defendant” subject to English jurisdiction, through which the plaintiff obtains permission to sue any other “necessary or proper party” to that claim.[53] LCC’s internationality is highlighted by its party composition, with 77% of its cases in 2019 involving at least one foreign party and 43% solely involving foreign parties.[54] As recorded in the latest Portland’s Annual Commercial Courts Report, which analyzes judgments from the LCC to identify notable trends such as the nationality and background of the users of the court and the drivers behind the use of LCC, litigants in the LCC in 2021 came from over seventy‑five countries.[55] The LCC has a remarkable caseload, with 1,476 hearings listed and 1,013 claims heard in 2020.[56]

The reasons for the LCC’s success are manifold.[57] First, the U.K.’s common law makes the LCC attractive to litigants. English law is regarded as the “go‑to” legal framework for international commerce.[58] According to Walker, the LCC becomes an ICC not by optimizing its procedural rules, but by setting itself out as a model for transnational commercial litigation.[59] This is particularly true when transnational commercial parties do not have a satisfactory judicial system in their home jurisdictions.[60] Similarly, a survey by the European Parliament revealed that English law is the leader in Europe’s litigation market.[61] Second, the availability of international interlocutory remedies under the English common law, such as anti‑suit injunctions and worldwide asset-freezing injunctions, provides extra protection to foreign litigants.[62] Third, the LCC’s use of English, a global lingua franca, in its court proceedings further consolidates its dominant position. Fourth, the LCC is a century old. Its first-mover status gives it another advantage over all other ICCs. The flip side of that coin, however, may be that the newer ICCs can be more flexible in creating unique and innovative court proceedings (for example, the introduction of foreign judges or use of UNCITRAL Model Law) to attract the market share from the LCC.

The strength of the LCC is not limited to its institutional excellence. Its primacy is also extended by its close proximity and historical connection with the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) and the London Maritime Arbitration Association (LMAA), over whose arbitral awards it exercises supervisory jurisdiction.[63] The availability of both quality litigation and arbitration for cross-border disputes in the same location creates an “agglomeration effect.” The same effect is found in other prominent legal hubs, such as Singapore.[64] Such agglomeration minimizes transaction costs and facilitates efficient dispute resolution.[65]

However, the LCC faces considerable challenges in the present-day. First, the LCC has increasingly fierce competition from other ICCs. In particular, the U.K. Ministry of Justice’s report highlighted the ICCs of New York, Singapore, and the European Union as key competitors of the LCC.[66]

Apart from that fierce competition, the LCC’s leading position is further undermined by the uncertainty caused by Brexit. A 2018 report by the European Parliament suggested that, after Brexit, commercial parties might be forced to consider alternatives to the LCC.[67] Indeed, the Portland Commercial Courts Report 2021 confirms that prediction, showing that the proportion of LCC litigants from EU member states declined from 14.9% in 2016–17 to only 11.5% in 2020–21. Given that the U.K. will be precluded from relying on the Brussels Regime, a mutual judicial recognition and enforcement regime inter se the EU member states, the enforceability of judgments rendered by the English courts in EU member states will be in doubt going forward.[68] However, an English judgment with valid choice-of-court agreements may arguably be enforced in EU member states via the Convention of 30 June 2005 on Choice of Court Agreements (“Hague Convention”) given that the U.K. is still a signatory to the Hague Convention. In any event, the significant level of uncertainty as to the impact of Brexit on the LCC could possibly compromise its core values of predictability and legal certainty. Indeed, as will be explained in Section II.C below, the uncertainty surrounding Brexit has prompted the proliferation of ICCs on the European continent, including the establishment of the ICCP, the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC), and the abandoned BIBC, all of which capitalized on this opportunity to compete with their London counterpart.[69]

2. The Commercial Division of the New York Supreme Court (NYCD)

The New York Supreme Court established the Commercial Division, dedicated to adjudicating complex commercial disputes, in 1995, in reaction to its loss of “adjudication business” to international arbitration and to the Delaware courts.[70] The jurisdiction of the NYCD is limited to high-value commercial disputes, with a current monetary threshold of $500,000 (exclusive of punitive damages, interests, costs, disbursements, and counsel fees).[71] For foreign cases with little or no connection to New York, the only requirements to establish jurisdiction before the NYCD are showing that: (i) the value of the dispute exceeds $1 million and (ii) there is a choice-of-forum clause whereby the parties agree to submit to the jurisdiction of the courts of the New York State.[72]

The NYCD covers a wide range of commercial cases, including land and conveyances, professional negligence (to a certain extent), and insolvency cases.[73] It also aims to attract transnational commercial parties by producing high‑quality judgments[74] with cultivating the perception of having lower litigation costs.[75] The NYCD also benefits from the economic power of the U.S. by attracting domestic parties and parties with assets in the U.S. At the same time, the NYCD has increasingly incorporated ADR elements within its conventional court procedures. For example, in 2019, it amended its Rule 3(a).[76] Under the new rule, the NYCD may “direct . . . the appointment of an uncompensated mediator for the purpose of mediating a resolution of all or some of the issues presented in the litigation” if the presiding justice finds that “it would be in the interest of the [case’s] just and efficient processing.”[77] This mediation service is free of charge for the first three hours of the session.[78] Additionally, the NYCD’s “Mandatory Mediation Pilot Project,” introduced from 2014 to 2016, refers “every fifth Commercial Division case” to the ADR Program for mandatory mediation sessions. According to an Administrative Order from January 28, 2016, this pilot program was positively received, showing the success of integrating ADR elements with traditional court procedures to form a “one-stop” legal hub.[79]

3. Findings on ICCs 1.0

A comparative study of the LCC and the NYCD elucidates their differences. The NYCD focuses more on the domestic litigation market. As the leading forum of commercial dispute resolution within the U.S.,[80] the NYCD attracts a significant amount of litigation of all types, but most suits come from U.S. parties.[81] Some have suggested that the NYCD has limited incentives to attract foreign parties because of New York State’s limited resources for subsidizing the judiciary.[82] This observation may betray a deeper underlying difference between the LCC and the NYCD: while the LCC is a court established within its country’s domestic legal system, the NYCD does not benefit from internal referral routes that operate among different U.S. state courts within the U.S. legal system.

There are, however, some commonalities between the LCC and the NYCD. For one, they are both located in “go-to” common law jurisdictions, which have well-established legal systems and rule-of-law traditions. Not surprisingly, at an institutional level, the infrastructures of the LCC and NYCD are both largely similar to the domestic courts of their respective jurisdictions. Additionally, even though both the LCC and NYCD are governed by local laws on jurisdiction, a choice-of-forum clause would be sufficient to establish their jurisdiction in these disputes.

Currently, although both the LCC and NYCD have enjoyed a relatively strong reputation in the international dispute resolution market, they are also facing increasing competition and challenges from other ICCs. As a result, there is a need for the ICCs 1.0 to consolidate their comparative advantages by keeping their dominant market positions. On the other hand, there may be limited room for improvements of the ICCs 1.0. Their reputations may preclude change. Because these ICCs rely on the inherent renown of their respective domestic legal systems, it would be difficult to make major structural reforms to them. Moreover, change may be restricted by the administrative limitations of their respective countries’ domestic courts, such as rules against the use of foreign judges.[83]

One further commonality among the ICCs 1.0 is their use of only domestic judges. Under the British judicial system, judicial appointments are only open to citizens of the U.K., the Republic of Ireland, or a Commonwealth country.[84] Similarly, the composition of the NYCD is subject to the U.S. citizenship requirement for appointing judicial officers under U.S. law.[85] The lack of foreign judges, however, does not seem to impede the development of these ICCs 1.0.[86] Both the LCC and the NYCD are embedded within their domestic judicial systems, and there is no standalone legislative framework governing the composition of judges and jurisdiction. These structural ties to the domestic judicial system would also imply that both the LCC and the NYCD are governed by their respective domestic jurisdictional limits.

This feature is in stark contrast with the substantial inclusion of foreign judges in ICCs 2.0 in emerging jurisdictions. The inclusion of foreign judges from well-established jurisdictions can boost the legitimacy and quality of the dispute resolution reputation of emerging jurisdictions. Table 2 below wraps up the important comparative features of the ICCs 1.0.

B. ICCs 2.0: Emerging Jurisdictions

Since 2006, there has been a wave of creation of new ICCs in emerging jurisdictions in the Middle East and Asia. These ICCs are markedly different from the ICCs 1.0, notably as to their use of a combination of domestic and international judges, their unique legal status within “jurisdictional carve‑outs,” and their drastically different methods of and motives for attracting foreign investment.

1. The Middle East ICCs

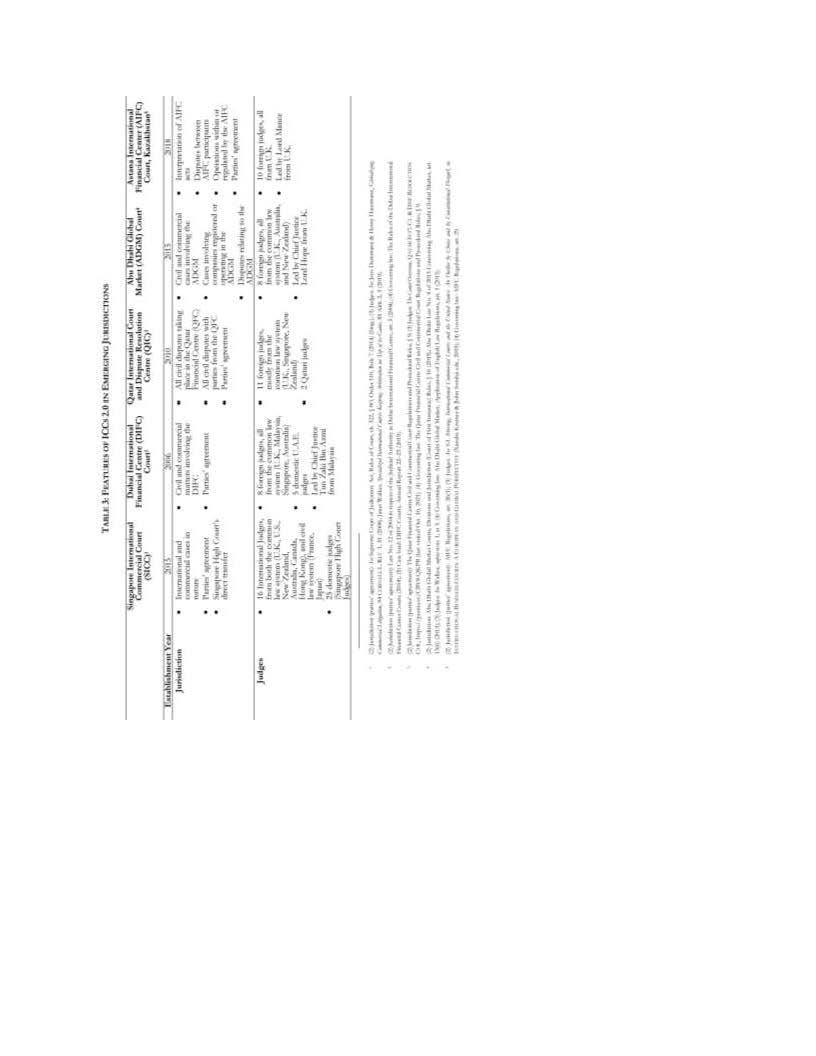

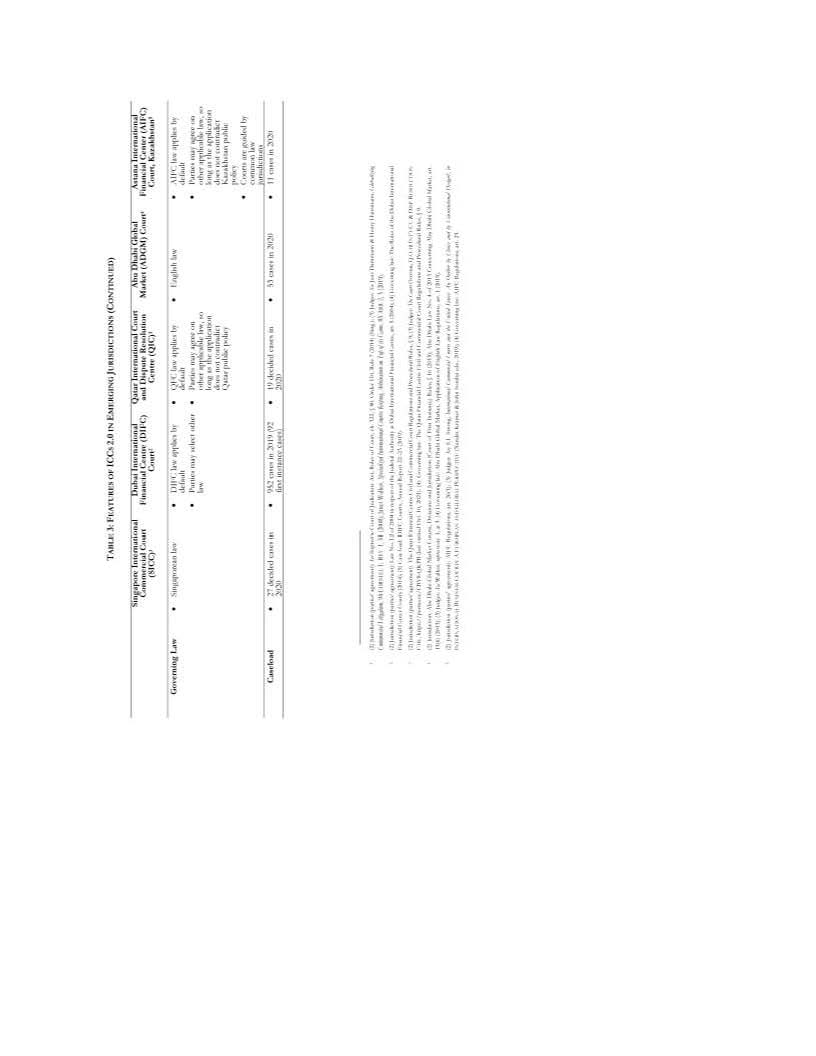

There are three notable ICCs in the Middle East: the DIFC Court in Dubai (established in 2006), the QIC in Qatar (established in 2010), and the ADGMC in Abu Dhabi (established in 2015). Comparative studies show that these three Middle East ICCs share a number of similar features.

These three ICCs all adopt a common law approach.[87] In terms of jurisdiction, they all deal with civil and commercial cases involving their respective Middle East regions.[88]

These courts all consist of a combination of domestic and foreign judges. The DIFC Court currently has thirteen judges: five domestic judges from the U.A.E., four judges from the U.K., three judges from Australia, and one judge from Malaysia.[89] The QIC, similarly, has two domestic Qatari judges and eleven foreign judges, from countries like the U.K., Singapore, New Zealand, South Africa, and Cyprus.[90] The ADGMC’s eight-judge bench is entirely composed of foreign judges from the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand.[91] The chief judges of all three courts are currently foreign judges: the DIFC Court’s Chief Justice is former Chief Justice of Malaysia Zaki Azmi, the President of the QIC is former Chief Justice of England and Wales Lord Thomas, and the ADGMC’s Chief Justice is former Deputy President of the Supreme Court of the U.K. Lord Hope.

All of these courts are situated in “exceptional zones”: economic zones in the Middle East that have substantially different legal systems from the countries in which they are located and thus are treated as “jurisdictional carve-outs.” While Islamic law is practiced in the countries in which they are located, the special economic zones adopt a distinctly Western legal system. One difference between Islamic law and English common law is Islamic law’s prohibition against riba, a form of interest charged on loans, which may deter foreign investment as it is not on par with international commercial practice.[92] For example, the ADGM has specific legislation, the Application of English Law Regulations 2015, that governs the region.[93] These Middle Eastern economic zones were set up, to promote trade and attract foreign investment.[94] The predominant motive of the three ICCs is to serve their respective economic zones. As admitted by the Chief Executive and Registrar of the DIFC Court in a 2018 speech, “the driving force has not been competition between courts for cases, but rather competition between countries for investment.”[95] This is a fundamentally different motive when compared with ICCs 1.0, whose main aim is to consolidate and enlarge their share in the global litigation market. The Middle East ICCs, on the other hand, were established to boost the confidence of foreign investors, thus promoting business for their particular economic zones.

The phenomenon of establishing ICCs in “exceptional zones” or “jurisdictional carve-outs” is shared among various emerging economies. Matthew Erie observed that exceptional zones, including special economic zones (SEZs) (for example, Shenzhen in China), free trade zones (FTZs) (for example, Shanghai Free Trade Zone in China), often overlap with emerging legal hubs such as the DIFC in Dubai and CICC in Shenzhen. It was further suggested that the exceptional zones may potentially lead to “jurisdictional turf wars” with their host states given their fundamentally different legal origins and jurisprudential basis.[96] Erie further suggested that from a wider anthropological perspective, such conflict can possibly produce ideological dissonance. For example, it was observed that the domestic courts in Dubai voiced discontent over the idea of “conduit jurisdiction” of the DIFC Court, arguing that its jurisdiction was unduly expanded.[97] As a compromise, a Joint Tribunal consisting of both domestic judges and judges from the DIFC Court was established in 2016 to adjudicate on cases of jurisdictional conflicts. Similarly, the proposal for establishing the BIBC in the European Continent encountered fierce pushback from the local judiciary. For example, when the Belgian Federal Government submitted the BIBC Bill, the High Council of Justice issued an open letter criticizing the “English‑speaking court project” (le projet de tribunal anglophone) with criticisms surrounding the BIBC’s impact on domestic courts, its impartiality, and source of funding.[98]

The Middle East ICCs use common methods of and have similar motives in attracting investors. First, they are heavily built on the basis of the U.K. legal system. All three courts draw foreign judges predominantly from common law jurisdictions, and both the QIC and ADGMC are led by former senior justices of the British supreme court levels. In light of the popularity of the English common law in resolving transnational commercial disputes, it is clear that the Middle East ICCs hope to attract investors by introducing the common law system.[99] As Michael Hwang (former Chief Justice of the DIFC Court) vividly put, the DIFC Court is a “common law island in a civil law ocean,” given that the U.A.E. laws are primarily based upon the civil law tradition.[100] This is a particularly bold and innovative move, given that the domestic law systems of the countries in which the Middle East ICCs sit are significantly different from the English common law.

Second, both the DIFC Court and QIC incorporate substantial ADR elements into the formal court proceedings. The QIC provides that judges can be separately appointed as arbitrators and administer arbitrations if the QIC is chosen as an arbitral seat.[101] The DIFC Court has gone even further, providing a mechanism for creditors to convert a monetary judgment rendered by the DIFC into an arbitral award via the DIFC’s collaboration with the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA).[102] In this way, the converted award will become an LCIA award that is globally enforceable under the New York Convention.[103] The process of converting a DIFC Court judgment to an LCIA award is as follows:

- The parties submit to the jurisdiction of the DIFC Court by a jurisdiction agreement together with an arbitration agreement requiring the Referral Criteria to be satisfied.

- The Referral Criteria includes an enforcement dispute between a judgment creditor and judgment debtor with respect to money claimed as due under a judgment.

- A judgment creditor can refer the “enforcement dispute” to the DIFC‑LCIA Arbitration Centre for obtaining a possible arbitral award.[104]

This unusual feature of converting DIFC Court judgments into arbitral awards is presumably because the U.A.E. is not yet a signatory to the Hague Convention. The Hague Convention enables mobility of judgments from courts of nations that are signatories to the Convention, thus facilitating global movement of judgments. Nevertheless, the DIFC Court judgments are enforceable in the Gulf Region by virtue of the Gulf Cooperation Council Convention for the Execution of Judgments, Delegations and Judicial Notifications.[105]

The DIFC Court has the highest volume of cases among the three ICCs in the Middle East. According to recent statistics, the DIFC Court had fifty‑four first instance cases recorded in 2017, followed by QIC with sixteen cases and ADGMC with thirteen cases.[106] The success of the DIFC Court seems to derive both from the quality of its bench and decisions and the innovation of converting DIFC judgments into LCIA arbitral awards.

2. Astana International Financial Centre Court in Kazakhstan (AIFC)

While Astana (renamed as Nur-Sultan in 2019), Kazakhstan, is located in Central Asia, the AIFC is similar to the Middle East ICCs. Like the Middle East ICCs, the AIFC sits within a special economic zone and borrows heavily from the U.K. common law system.[107] In addition, the AIFC is guided by other common law jurisdictions, which makes the AIFC more connected with common law jurisprudence around the world.[108]

Erie pointed out that the AIFC is not entirely a replica of the DIFC Court model. On the one hand, the AIFC does not serve as a conduit jurisdiction and hence avoids the encroachment of jurisdiction concern from the domestic courts as in Dubai’s case.[109] As seen from the Dubai experience, the DIFC Court once positioned itself as a “conduit jurisdiction,” under which litigants may seek to enforce a foreign judgment in the onshore Dubai courts via the DIFC conversion mechanism even if there is no connection between the foreign judgment and the DIFC Court.[110] Such a “short-cut” enforcement path was the subject of criticism because it may bypass the local Dubai courts and may constitute an encroachment upon the jurisdiction of the onshore Dubai courts. This sentiment also led to pushback from the Joint Tribunal of the Dubai Courts and the DIFC, which ruled that the onshore Dubai courts shall have the prevailing jurisdiction over the DIFC on parallel proceedings.[111] By contrast, the AIFC adopted the “opt-in” model, a jurisdiction based on the free election of parties.[112] On the other hand, the AIFC does not form part of the judicial system of Kazakhstan. It is an independent court within the AIFC economic zone.[113]

The AIFC also has arguably greater ambitions than do the Middle East ICCs. While the latter focus on parties from the Gulf region, the AIFC targets parties across the Eurasian region.[114] This is a much larger geographical reach than the AIFC economic zone per se. One possible explanation for the AIFC’s ambition may be the unique geographical location of Kazakhstan. Notably, the AIFC’s target region is likely to overlap with China’s BRI and may potentially compete with the CICC in the BRI litigation landscape. In fact, the Kazakhstan government has launched the “Nurly Zhol,” a national infrastructure development initiative focused on transforming Kazakhstan into a major Eurasian hub by developing and modernizing roads, railways and ports in Kazakhstan.[115] Given the significant geographical and political overlap, this would make the AIFC a potential competitor with the CICC.

With respect to jurisdiction, the AIFC accepts disputes that involve interpretation of the AIFC Acts, between AIFC participants, on operations within or regulated by the AIFC, and by parties’ agreement.[116] It currently has eleven judges who are all from the U.K., with former Deputy President of the Supreme Court of the U.K., Lord Mance, as its Chief Justice.[117] The AIFC law is guided by common law principles, and parties may agree on applicable law so long as such law does not contradict the Kazakhstan public policy.[118]

3. Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC)

The SICC, established in Singapore in 2015, is arguably the most competitive among the ICC 2.0 group. It is considered a key competitor with the LCC, as identified by the U.K. Ministry of Justice in a 2015 report.[119] This is a remarkable achievement, given that Singapore’s legal history is much shorter compared to that of the U.K. and, likewise, the SICC vis‑à‑vis the LCC. As a common law jurisdiction in Asia, Singapore is also much smaller than the U.K. in terms of geographical size and population. Singapore is also less established in terms of its volume of cases and jurisprudential development.

An important distinguishing factor of the SICC lies in its wider target market. Unlike other ICC 2.0 group courts that focus on facilitating the development of a particular economic zone (for example, the DIFC, QIC, and AIFC ) the SICC aims to promote the entire country of Singapore in terms of transnational dispute resolution services for international users.[120] One of the major aims of the SICC is to develop “a freestanding body of international commercial law” for the international audience.[121] As such, while the majority of claims in the Middle East ICCs involve Middle Eastern clients, the SICC serves clients from around the world and focuses primarily on international disputes.[122]

Another key feature is the strong support from the host state, as the SICC has strong government backing. The idea of establishing the SICC can be traced back to the Opening of Legal Year 2013 where Chief Justice of Singapore Sundaresh Menon shared his vision for the creation of an SICC that would expand the internationalization and export of Singaporean law.[123] Shortly after, the Chief Justice and the Minister of Law, K. Shanmugam, announced that an SICC Committee would be created to study the viability of the establishment of the SICC.[124] In the model of the SICC, there has been a close collaboration between government department/ministers and the judiciary in the policy‑making of judicial capacity‑building. This echoes Erie’s remarks that the government plays a central role in most of the NLHs by having controlling stakes in the “corporate entities” of the dispute resolution services.[125]

It has been suggested that the SICC’s success can be attributed to its reputable and internationally diverse bench and its flexible procedural rules.[126] The procedural rules of the SICC are strongly influenced by the arbitration procedural model, triumphing party autonomy. A typical example is that the “open court” presumption can be overridden by parties’ agreement or by parties’ application to the court for a confidentiality order.[127] In other words, the SICC will take a more liberal approach in dealing with international commercial disputes than do the domestic courts.[128] These strengths can be summarized by the delicate balance between borrowing from the traditional English common law system and making innovations distinct from other ICCs. Moreover, Singapore’s top-down ambition in constructing a suite of premium dispute resolution services has been shown in the agglomeration of the SICC, SIAC, and the SIMC (together, the SICC‑SIAC‑SIMC).[129] In 2010, the Maxwell Chambers was set up in Singapore to accommodate the SIAC and the SIMC, an arrangement which facilitates “one‑stop‑shop” dispute resolution services for international users and minimizes costs through cross-institutional cooperation.

Structurally, the SICC is a subdivision of the Singapore High Court, which is part of the Supreme Court of Singapore, and designed to deal with transnational commercial disputes.[130] In terms of its jurisdiction, the SICC has the power to hear cases if the dispute is of an international and commercial nature and parties have directly submitted to the SICC jurisdiction under a written jurisdiction agreement.[131] There is no requirement that the case has an actual connection with Singapore. The choice of the SICC in the jurisdictional agreement as the only connecting factor would suffice.[132] Moreover, the SICC has jurisdiction to hear cases transferred directly from the Singapore High Court, which means the SICC has a stable intake of cases in addition to the cases submitted via parties’ jurisdiction agreements.[133] Hence, its caseload is guaranteed. The intake of cases from internal referral resembles the LCC, which is a division of the English High Court, whereas the case intake via the parties’ jurisdiction clauses mirrors international arbitration. This “party opt‑in” feature, without the need to establish any link to Singapore, makes the SICC a “hybrid” court offering complementary services between traditional court proceedings and international arbitration, which significantly enhances its competitiveness and is unparalleled among the ICC 2.0s.

Apart from guaranteed caseload, the cost of proceedings in the SICC is reasonable. The current daily rates for a single-judge‑bench and a three‑judge‑bench for trial at the SICC are fixed at SG$3,500 and $10,500, respectively.[134] The clear rules for fees, charges, and the reasonable costs set out in the Singapore Rules of Court provide predictability for businesses to conduct proceedings in the SICC. This can be contrasted with the concern voiced over the cost and time spent in international arbitration.[135]

There are currently sixteen International Judges sitting on the SICC bench in addition to the eighteen domestic Singapore High Court judges.[136] Different from other ICCs 2.0 courts, which draw overseas judges exclusively from common law jurisdictions (predominantly the U.K.), the SICC draws judges not just from a broader group of common law jurisdictions (the U.K., the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Hong Kong), but also leading civil law jurisdictions (such as France).[137] The SICC draws from a wide pool of judicial talents from both the East and the West.[138] Arguably, the judicial profile is more internationally diverse and boasts expertise across a broader range of legal systems and culture as compared to both the ICCs 1.0 and other ICCs 2.0 counterparts. As the latest statistics show, thirty cases were decided at the SICC in 2020.[139] The total decided caseload at the SICC has reached ninety‑five since its establishment in 2015.[140] Notably, there has been an increase in the SICC caseload in 2020, which can be contrasted to the LCC (an example of an ICC 1.0) which saw a decrease in its usual case volume.[141]

4. Findings on ICCs 2.0

ICCs 2.0 are established to serve the economic interest of a particular country or an economic zone, with three salient features as follows. First, a common feature of these economic zones is their aim to increase parties’ confidence and improve the quality of the court’s decisions and to attract foreign investment and commercial parties by borrowing features from ICCs 1.0 (i.e., the common law system). Second, while ICCs 2.0 look to ICCs 1.0 for guidance, the former have more innovative features. For example, although the home countries for many ICCs 2.0 do not have common law legal systems, some of them have carved out areas of common law with constitutional amendments or regulatory changes. This is unparalleled among ICCs 1.0, which established themselves as domestic courts embedded within their own national legal systems. Third, a considerable number of foreign judges (especially from common law jurisdictions) are introduced to the ICCs 2.0. In addition, the SICC in Singapore has stood out among the ICCs 2.0 as an unconventional, hybrid court model by offering complementary services between traditional court proceedings and international arbitration. The SICC is an integral part of the Singapore High Court—its mother court—and can hear cases directly transferred from its mother court. This intake of cases from internal referral has inspired the CICC in China to be affiliated with the Chinese Supreme People’s Court, which will be analyzed in the ICCs 3.0 group. Moreover, ICCs 2.0 have evolved in the direction of being comparable to international arbitration. This is particularly evident in the case study of the SICC. Singapore allows the SICC to assume jurisdiction over disputes without any link to Singapore and then relies on the Hague Convention to facilitate global judgment mobility to mirror what the New York Convention does for global enforcement of arbitral awards.[142] In addition, Singapore allows for judges with foreign and international law expertise of both common law and civil law backgrounds, which parallels the ability to pick arbitrators with the most suitable expertise, an example of the evolution of ICCs 2.0 to become increasingly internationalized and competitive to attract the widest range of disputes possible. This evolutionary trend of amassing newer features of international arbitration and increasing comparability to international arbitration service providers is also evident in the wave of the ICCs 3.0.

Table 3 summarizes the comparative features of the ICCs 2.0.

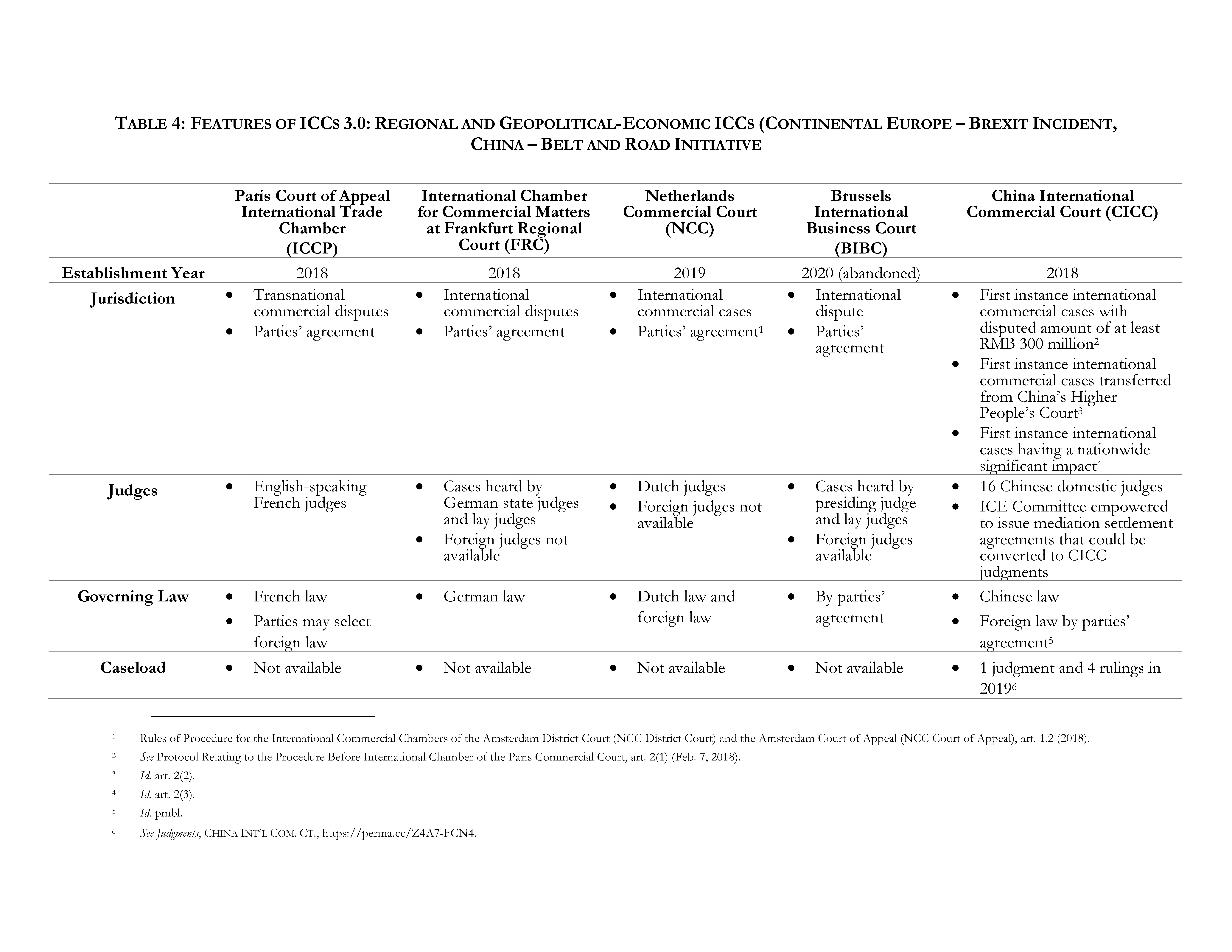

C. ICCs 3.0: Regional and Geopolitical-Economic ICCs

Recent changes in the world’s political and economic trends have prompted the proliferation of ICCs 3.0, with different underlying regional politico‑economic motivations. The home states of these ICCs are neither traditional common law jurisdictions nor emerging niche jurisdiction carve‑outs. In fact, the rise of ICCs 3.0 is in response to specific regional geopolitical‑economic incidents: Brexit and the Belt and Road Initiative. In this respect, ICCs 2.0 and 3.0 may have a certain degree of overlap as they both aspire to boost the economic and/or legal development of their host states. One way to further distinguish ICCs 2.0 and 3.0 is that ICCs 2.0 show evident features of common law “transplant” in emerging jurisdictions such as Singapore and Abu Dhabi, with prominent English judges as judges for SICC and ADCC and common law as their default governing law. By contrast, ICCs 3.0 consist of jurisdictions that are rooted in civil law traditions, such as France, Germany, Belgium, and China, and are generally less receptive to the influence of foreign law. As such, ICCs 3.0 distinguish themselves from the “transplant” regimes of the ICCs 2.0 in locations such as Singapore, Qatar, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi which are heavily influenced by English common law.

1. European ICCs

France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium all established their own ICCs soon after the U.K.’s decision to withdraw from the European Union, commonly known as Brexit. The proliferation of ICCs in the European Continent reflects the European states’ ambition to draw dispute-resolution business from the LCC in London.[143] In fact, the European Parliament published a report in 2018 to consider how member states’ dispute resolution mechanisms can be strengthened in light of Brexit.[144] One key finding is that the LCC would lose the advantage of judicial cooperation among EU courts—such as the reciprocal recognition and enforcement of monetary judgments—forcing commercial parties to consider alternatives to the LCC.[145]

To compete with the LCC, these European ICCs incorporate several common law elements. The most notable feature is the use of English in court proceedings. For example, the NCC in Amsterdam adopts English as the language for court proceedings and final judgments.[146] The NCC also allows for the possibility of choice of foreign law, including English law).[147] These features specifically cater to English-speaking commercial parties, and the NCC prides itself as an “English-language environment within a civil law jurisdiction.”[148] However, these European ICCs are less willing to fully embrace the common law system and English language in their domestic jurisdictions than ICCs 2.0 are, given their deeply entrenched civil law tradition. For example, the general rule at the ICCP in Paris is that both the written submissions and court judgments must be made in French, although parties can produce oral submissions and expert evidence in English.[149] The FRC in Frankfurt likewise prescribes that German must be the language of the court proceeding due to restrictions under § 184 of the German Courts Constitution Acts (Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz or GVG).[150] This sheds light on the role of legal tradition and culture in the establishment of ICCs.

A comparative study of these continental European ICCs shows that the proposed but abandoned BIBC in Brussels would have been the most distinctive. While the German, French, and Dutch ICCs stand as specialist chambers within domestic court systems,[151] the BIBC would have been a standalone court independent from its local judiciary. The BIBC aimed to bring litigation and arbitration closer together. For instance, its procedural rules would have mimicked the Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL Model Law).[152] Specifically, the BIBC planned to adopt Article 28 of the UNCITRAL Model Law, which essentially follows the “free choice model.”[153] Furthermore, the BIBC cases would have been heard by both professional judges and international business law specialists.[154]

All these features are borrowed from arbitration. Despite its innovative institutional breakthrough, the draft bill faced fierce pushback from the Belgian domestic judiciary (High Counsel of Justice), which primarily questioned the feasibility of its “two-tiered justice,” the source of funding, and its impact on domestic courts.[155] Other controversial issues related to the BIBC proposal include the language of proceedings and the perceived over-reliance on procedural law based on the UNCITRAL Model Law.[156] This, coupled with a changing political climate in Belgium, led Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel to quietly withdraw the draft BIBC bill.[157] As of October 2021, Belgian scholar Stefaan Voet observes there is little appetite in the current Belgian government to resuscitate the bill.[158] However, despite the BIBC’s failure, it still serves as an important inflection point for ICCs based on two grounds. First, the draft BIBC serves as a model for ICCs that can be replicated in some capacity in the future. BIBC’s proposed design to adopt the UNICTRAL Model Law as the procedural framework reflects the most recent and forthcoming interface between ICCs and international arbitration. This wave of “arbitralization” of ICCs is highlighted in Section IV.C below.[159] Second, the demise of the BIBC proposal further entrenches the importance of having top-down government backing. One crucial factor behind the abandonment of the BIBC was the lack of government support, coupled with the pushback from its local judiciary.[160] For any future ICC developments, a key lesson from the BIBC case study is that having government backing is a necessary condition, if not a precondition. For example, such top‑down support was well demonstrated in the success of the SICC.[161]

With respect to jurisdiction, the ICCP in Paris accepts transnational commercial disputes that are related to international commercial contracts, transportation, unfair competition, and other financial transactions.[162] There is no requirement for a connection with the host state, France. As long as there is (i) parties’ consent via a choice of court agreement electing the Paris Court of Appeal as the designated court and (ii) the case has an element of international business, the ICCP may have jurisdiction.[163] However, the parties cannot explicitly opt for ICCP as the forum because all cases need to first pass through the Placement Chamber, which is a special chamber within the Paris Court of Appeal responsible for allocating disputes to different divisions of the same.[164] The Placement Chamber is similar to the role of a traffic controller.

In Germany, the FRC at Frankfurt hears disputes that satisfy the following requirements: (i) it is a “commercial matter” within the meaning of § 95 of the German Act on the Constitution of Courts (GVG); (ii) it is international; (iii) it does not fall under the special jurisdiction of another chamber of the Regional Court of Frankfurt; and (iv) the parties had a choice of court agreement and had declared that they wanted to plead in the oral proceedings in English and waived the right for an interpreter.[165] As to the NCC in Amsterdam, it does not require any connection to the Netherlands as long as parties agree to the NCC’s jurisdiction.[166] The approach taken by the FRC and NCC is similar to that of the SICC, in which the only connection required is the parties’ choice of court agreement.[167] In November 2020, the Stuttgart Commercial Court (SCC) and Mannheim Commercial Court (MCC) were established as specialist commercial divisions of the Regional Courts pursuant to § 95 of the GVG.[168] Both the SCC and MCC hear complex commercial disputes of at least €2 million at stake.[169] One key feature of the two courts is that parties are entitled to opt for an adjudication panel with one regular judge and two lay commercial judges who are experienced businessmen.[170] The participation of lay judges is intended to inject commercial expertise from the business sector into the judicial bench, thereby enhancing public confidence in the German court system.[171] Similar to the ICCP, the SCC permits proceedings to be conducted in English, as all regular judges on the SCC bench possess English language proficiency.[172] Parties may appeal to the Courts of Appeals of Stuttgart and Karlsruhe.[173]

The proposed BIBC in Belgium would have been the most “liberal regime,” and the jurisdiction of the BIBC would have gone further than all the aforementioned Continental European ICCs. As stipulated in Art. 576/1(2) of the Belgian Judicial Code,[174] the BIBC would have had jurisdiction via one of two routes: (i) through a choice of court agreement submitted to the BIBC; or (ii) through a referral by another Belgian, foreign, or international court or tribunal, including an arbitral tribunal, in which the parties’ consent to the referral is declared.[175]As such, in addition to the conventional first route where parties submit directly to the BIBC via a choice of court agreement, there would have been a second unconventional route of referrals from foreign courts, or even arbitral tribunals, so long as the parties consented to the referral order made by these external tribunals. It is the “referral” route that would have distinguished the BIBC from the NCC/FRC/SICC’s “choice of court agreement as a sole connection” feature. In other words, the “pre-concluded” choice of court agreement could be substituted with parties’ consent to the declaration of referral by a foreign court or an arbitral tribunal at a “post-commencement” stage.[176]

This would have been by far the most liberal regime in terms of the jurisdiction of the existing ICCs. A post-commencement consent to the referral declaration by any foreign court or an arbitral tribunal would have also given rise to the BIBC’s jurisdiction. This feature is distinguishable from the regime under the FRC, the NCC, and the SICC on the grounds that the latter ICCs do not allow a referral route via external tribunals (judicial or arbitral). For example, the SICC only provides for an internal referral mechanism from the Singapore High Court to the SICC or by parties’ choice of court agreement.[177]

As for governing law, all ICCs 3.0 use their own domestic law subject to parties’ intentions otherwise. For example, the ICCP and the NCC both allow parties to select foreign law.[178] As mentioned, the proposed BIBC would have been the most innovative court on the issue of governing law because of its plan to adopt the UNICTRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration as its procedural rules.[179]

European ICCs take varied approaches to the backgrounds they require of their judges. There is no foreign judge available in the NCC, though Dutch judges are believed to have good command of English.[180] In Paris, the ICCP is staffed with French judges who can speak English and have English common law reasoning capabilities.[181] The design of the FRC bench in Frankfurt is markedly different from those of the NCC and ICCP. Each FRC bench sits three domestic German judges: one professional judge and two lay business experts.[182] Among the European ICCs, the BIBC panel composition would have been the most intriguing. It was to be composed of (i) a Chairman, who is a professional judge from the Brussels Court of Appeal Market Court, (ii) a Panel Chairman, who is also a Belgian professional judge with knowledge in international trade law, and (iii) BIBC Judges, who are lay judges chosen from a list of international trade law specialists from Belgium and beyond.[183] For (iii), there was no requirement that the judge be Belgian or a European citizen, nor was Dutch or French language proficiency needed. Thus, non-European judges could have been appointed to the list of eligible lay judges. However, since the list of lay judges would have been nominated by the Belgian business sector under Articles 202, 204, and 216 of the Belgian Judicial Code, it remains uncertain to what extent the BIBC judges would have featured non-European businessmen.[184]

The intra-regional competition among the European ICCs may improve the competitiveness of each individual ICC, as each of them has sought to develop its own niche by creating user-friendly court features (for example, language or use of international judges) and delivering quality judgments.[185] Nonetheless, there may be conflict and overlap between these courts. As a result, their competitiveness against the LCC, a single court within a coordinated common law legal system, might be hindered. In light of this potential conflict, there have been calls for a combined and consolidated European Commercial Court (ECC).[186] It is believed that such an ECC would benefit from a truly neutral and international nature, which would give it more flexibility in terms of appointing international judges and allow it to compete directly with other regional ICCs.[187] However, there have not yet been any concrete plans taken by the European Union in this direction. It is possible that such plans will not emerge anytime soon, given the recency of the emergence of the European ICCs.

2. China International Commercial Court (CICC)

While Europe has been occupied with Brexit and its aftermath, China has been rolling out its ambitious economic and diplomatic plan, the BRI. The BRI ambitiously aspires to expand regional markets and facilitate economic integration across Asia, Africa, and Europe.[188] It has been regarded as a game‑changer in the landscape of dispute resolution and is expected to trigger a proliferation of adjudication business.[189]

The CICC was established in 2018 to cater to China’s leading role in the BRI, with the specific goal of facilitating dispute resolution among BRI countries.[190] The CICC is governed by the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Regarding the Establishment of the International Commercial Court (CICC Provisions).[191] It consists of two courts: the First CICC in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, for handling BRI-related international commercial disputes arising out of the sea-based Maritime Silk Road; and the Second CICC in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, for handling BRI‑related international commercial disputes arising out of the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt.[192] Shenzhen was chosen for its traditional role as a test bed of new legal and economic policies and for being closer to the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Great Bay Area. Xi’an was chosen in part for its historical position as the starting point of the ancient Silk Road.[193] Meanwhile, the Fourth Civil Division of China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in Beijing, which specializes in trials of international commercial disputes in China, is responsible for coordinating and guiding the two CICCs.[194]

As of February 2021, all sixteen judges appointed to the CICC are mainland Chinese, selected from senior judges familiar with international laws and norms and proficient in English and Chinese; nine out of the sixteen judges either visited or studied at a university outside mainland China.[195] The introduction of foreign judges has been prohibited by Chinese law (for example, Art. 12 of China’s Judges Law stipulates that a judge in China must be of Chinese nationality).[196] Faced with this obstacle, the CICC innovatively introduced international expertise through its niche product, the International Commercial Expert Committee (the ICE Committee).[197]

There are three major provisions in the establishment of the ICE Committee: (i) the CICC Provisions, (ii) the Working Rules of the ICE Committee,[198] and (iii) Procedural Rules for the CICC of the Supreme People’s Court (For Trial Implementation).[199] Article 11 of the CICC Provisions provides that an ICE Committee is established to create a “one-stop” international commercial dispute resolution mechanism at the CICC.[200] As set out in Article 3 of the Working Rules of the ICE Committee of the SPC, members of the ICE Committee may have two key duties: (i) to preside over mediations and (ii) to provide expert opinions on findings of foreign law.[201] The mediation duty of the ICE Committee is an integral part of the CICC’s ambition to set up a “One‑Stop Multi-tier Dispute Resolution Platform,” as prescribed by Article 11 of the CICC Provisions, “with the promotion of arb-med as one of its top priorities.”[202] The most notable of the many ground-breaking features of the ICE Committee is that if a settlement agreement has been reached after the presiding of mediations by the ICE members, the CICC may issue a judgment based on the mediation settlement agreement.[203] In this way, the foreign members of the ICE Committee are indirectly allowed to pass “judgments” via the mediation mechanism.[204] This is by far the most liberal feature of the CICC in terms of internationalization and may potentially somewhat offset the international concerns about and scepticism of its lack of international elements (particularly on foreign judges).

Apart from encouraging parties to settle their disputes, the CICC also allows the ICE Committee to give advice on foreign law. Another statutory obstacle is Article 262 of the 2017 Chinese Civil Procedure Law, which stipulates that hearings of foreign-related cases must be in the language commonly used in China (for example, Chinese Putonghua).[205] The extent of the CICC’s introduction of international elements stops at the ICE Committee. This may affect the CICC’s competitiveness when all other ICCs in Asia and along the BRI roadmap feature foreign judges (such as the SICC in Singapore, AIFC in Kazakhstan, and ICCs in the Middle East). With a limited degree of internationalization, the CICC may not attract as many international parties as its peers. In the long-term, it is proposed that judicial reforms would be carried out to introduce elements of internationality into both the CICC bench and legal representation by revising Article 9 of the Chinese Judges Law and Article 262 of the Chinese Civil Procedure Law.[206]

Despite the CICC’s potential limitations, the court could benefit from the BRI directly. Commercial parties in BRI-related contracts, influenced by China’s economic power, may specifically designate the CICC for dispute resolution. However, it is unclear whether this will be a commercially sound and sustainable practice for the CICC. On the other hand, mirroring the SICC’s placement as a subdivision of the Singapore High Court, the CICC was made a subdivision of the SPC in Beijing, a structure that guarantees a healthy flow of cases by transfers and referrals.[207] Thus, the CICC, like the SICC, should have a stable intake of cases in addition to cases directly submitted by parties’ jurisdiction agreements.

There are three features of the CICC that deserve particular attention. First, the ICE Committee’s function as a mediator and a foreign law expert is no doubt a sign of internationalization by the CICC. The fact that the mediation settlement agreements can be converted into the CICC judgments is arguably in parallel with the DIFC Court’s innovation to convert judgments into arbitral awards.

Second, the CICC actively embraces the concept of a “one-stop” center for multi-tiered approaches to international commercial dispute resolution services, integrating litigation, arbitration, and mediation.[208] The notion of a one‑stop‑shop echoes the multi-door courthouse envisioned by the late Harvard professor Frank Sander, who envisaged that future courts should provide a menu of options for dispute resolution back in the 1970s.[209] A concrete example is that the CICC Procedural Rules provide for pre-trial mediation procedures upon the plaintiff’s consent.[210]

Last but not least, the CICC strives to achieve technological innovation. As stipulated in Article 4 of the CICC Procedural Rules, the Court supports an online process for case acceptance, payment, service of process, mediation, file inspection, evidence exchange, pre-trial preparation, and hearings.[211] The case management and pre-trial conferences can be held via online video calls.[212] The parties may also apply for an online video trial.[213] In a recent visit to the Singapore Maxwell Chambers, which houses the SIAC and the SIMC, Erie observed that the Chinese delegates actively asked questions regarding the role of technology in ADR proceedings when interacting with the Singaporean representatives.[214] To a large extent, this reflects the determination of China to achieve technological innovation while constructing its own legal hub.

3. Findings on ICCs 3.0

Established in response to a particular regional politico-economic incident or policy, ICCs 3.0 focus on attracting parties in response to that event or policy more than simply promoting the home jurisdiction’s dispute resolution market in general. Thus, ICCs 3.0 often have specific economic, political, or diplomatic motivations and are regional in nature. Both the post‑Brexit ICCs in continental Europe and the CICC in the Eurasian Belt and Road regions are examples of ICCs 3.0, reflecting the trend of ICC development in response to regional or geopolitical economic phenomena. The factors that motivate the development of these ICCs may on the one hand stimulate, or on the other hand hinder efforts to promote their competitiveness. The top-down, government-initiated approach could be more effective in achieving geopolitical aims due to the availability of national resources like financing and strategic expertise.[215] However, the underlying politico-economic motivations could instead undermine the impartiality of the newly established courts, diminishing their attractiveness to foreign investors. Moreover, compared to ICCs 2.0, ICCs 3.0 are subject to more constraints from their home countries’ domestic legal systems. As such, the success of ICCs 3.0 hinges on the extent of their home state’s support. ICCs 3.0 with state support are typically more successful, but those that lose support or face competing local forces or institutions face more hardships, as in the example of the failed BIBC.

Although ICCs 3.0 are themselves comparatively less internationalized, the opportunities prompting their establishment boost their competitiveness. These ICCs are established in response to new opportunities arising from politico‑economic developments. The European ICCs aim to attract post‑Brexit litigation business, and the CICC hopes to benefit from the prospective volume of BRI-related litigations. It is possible that these ICCs could develop their reputations through these unique opportunities. Moreover, ICCs 3.0, following the evolutions of ICCs 2.0, have also largely incorporated newer features of international arbitration to make themselves as welcoming as international arbitration. Table 4 below summarizes the key comparative features of the ICCs 3.0.

IV. Power Dynamics

A. The Concept of “Co-Opetition”

The study of the ICCs throughout the globe resonates with that of the international financial centers. Douglas Arner identified six different types of financial centers in the world: (i) global, (ii) international, (iii) regional, (iv) niche, (v) domestic national, and (vi) domestic regional.[216] As discussed in Section III.A, ICCs 1.0 are courts in established jurisdictions (for example, the LCC and NYCD). In parallel, Arner categorized London and New York as “global” financial centers. while Hong Kong was identified as an “international” financial center.[217] Singapore, being a hub for the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Southeast Asian market, is regarded as a “regional” center.[218] The concept of a regional hub mirrors the ICCs 2.0, which are emerging jurisdictions with a specific geographical focus. The Middle East ICCs, which include the DIFC Court, QIC, and ADGMC, may fit into the model of “regional” centers given that they mainly cater to specific Middle East regions (for example, the DIFC zone and the Qatar Financial Center area). In the meantime, they can fit into the model of “niche” centers because of their specialized provision of services (for example, the Islamic finance and Islamic commercial dispute resolution).