WIPO’s Proposed Treatment of Sacred Traditional Cultural Expressions as a Distinct Form of Intellectual Property

For the past twenty years, the United Nations’ World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has been working on what could be a major shift in international intellectual property law. WIPO’s work has uniquely focused on intellectual property protection for “traditional cultural expressions” (TCEs), a term which roughly describes a broad conception of indigenous groups’ intellectual property. Most recently, WIPO published its latest proposed Draft Provisions/Articles for the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions, and IP & Genetic Resources. These Draft Provisions propose a tiered rights system in which the owners of sacred TCEs receive more protective rights than the owners of secular TCEs. While the instinct to protect the intellectual property of indigenous groups is admirable in light of indigenous groups’ exploitation and exclusion from Western intellectual property regimes, a protection system that all nations accept has been difficult to reach. Even more so, a system that differentiates among TCEs based on their sacredness will need to be justified to convince as many nations as possible (or at least a critical mass of nations that heavily influence international intellectual property policy) to adopt WIPO’s proposed system. Assuming that a novel system for TCEs protection is a generally good idea, this Comment explores potential justifications for the Draft Provisions’ sacred versus secular distinction.

Potential justifications can be divided into three categories: value-based, harm-based, and traditional IP justifications. Value-based justifications suggest that sacred TCEs should receive heightened protection because they are more valuable, either economically or intrinsically. Harm-based justifications suggest that sacred TCEs should receive heightened protection because of the harms that would come about if they did not receive this protection, such as devaluation, cultural extinction, offense, and desecration. Traditional IP justifications suggest that sacred TCEs should receive heightened protection for the same reasons that IP generally should be protected, such as: incentivizing creativity and distribution; rewarding labor; personality, autonomy, and personal development; and developing a just and attractive society. Of these justifications, the most convincing are economic value justifications and just and attractive society justifications. Framing potential justifications in terms of justifications already familiar to the IP field will increase the likelihood of a critical mass of nations adopting the Draft Provisions.

I. Introduction

From March 24 to April 4, 2014, almost 200 international entities met in Geneva, Switzerland. The topic on the agenda was developing an international legal protection system for indigenous peoples’ traditional cultural expressions (TCEs)—a term used to describe what some would call “cultural heritage.” Essentially, the countries and organizations were gathered to discuss how to use international intellectual property (IP) law to protect against cultural misappropriation.1 During one of the meeting’s sessions, the United States delegation said the following: publicly available and widely diffused TCEs did not “lend themselves to protection by exclusive right” partly because their origins “might be difficult to trace.”2 It then gave an example based on the history of blue jeans. Italian sailors used to wear heavy blue pants. French manufacturers then produced those pants using local production techniques and materials. U.S. manufacturers then improved upon that fabric to make what eventually became the blue jeans used by gold miners in California. The U.S. delegation pointed out that granting exclusive rights to blue jeans might have a devastating impact on many current blue jeans manufacturers. Even setting this aside, if the method of making denim and blue jeans was a TCE, to which community did it belong?

Later in the meeting, the representative of the Tulalip Tribes of Washington state responded to the U.S. delegation’s example by giving another example. In 1984, an airplane flew over a Puebloan kiva3 and took pictures of a sacred ceremony being performed within.4 The photographers then published the pictures. The Pueblo people objected to this, but they had no recourse because at the time “the law said that the air space was free” and others had apparently suggested that “if the group wished to protect their ritual, they should cover their Kiva.”5 While the Pueblo people had arguably made their ceremony publicly available, the Tulalip tribe representative pushed back on this characterization, saying that “if it was requested that traditional practices [be] changed in order to accommodate the existing IP system, he [had] some issues in relation thereto.”6

The Tulalip representative used this example to caution against equating the U.S.’s blue jeans example to the sacred ceremony example. He “asked whether there was a difference in the methodology of blue jeans versus the rituals and ceremonies that may have been used since time immemorial, and where there may be deep spiritual issues associated with the practices and issues of cultural identity and integrity.”7 Additionally, “he wondered whether the [committee] should be putting all these examples in the same box.”8 Later in the meeting, the delegation from New Zealand echoed this sentiment, saying that “[w]hen one participant talked about jeans and another talked about sacred rituals, there was a sense of which they were talking past each other . . . [and] that the [committee] should look more closely at whether the type of protection should vary depending on the type of [TCE] in question.”9 This conversation led to a proposal for differentiated protection based on the type of TCE.10

These countries, IGOs, and NGOs were gathered in Geneva for a meeting of the Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC), a World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) committee that focuses on indigenous IP issues. WIPO is a U.N. agency focused on IP services, policy, information, and cooperation.11 To achieve these goals, WIPO holds regular meetings to discuss international IP issues, administers most major international IP treaties, and proposes policy changes.12

In March 2004, the IGC began developing the Draft Provisions/Articles for the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions, and IP & Genetic Resources (the “Draft Provisions”).13 The Draft Provisions were also born out of Member States’ positive reaction to the IGC’s work cataloging the types of legal protection specially designed for expressions of folklore and TCEs.14 These interchangeable phrases are used to describe indigenous “soft intellectual property” (i.e., works protected by IP mechanisms such as copyright,15 trademarks,16 and trade secrets17 ). This Comment will primarily use the phrase “TCEs” because it is the more modern phrase.18 However, the shift towards TCEs is recent, so many of the sources cited throughout use “expressions of folklore” or simply “folklore.” There is, however, no substantive difference between these terms and TCEs. Section II.A.2 describes TCEs in more detail.

Recognizing the elevated harms that misappropriation of sacred TCEs can cause to an indigenous community, WIPO proposed a tiered rights system in which creators of sacred TCEs receive more rights relative to creators of secular and widely diffused TCEs. Because the proposal is still in its draft phase, the Draft Provisions include two proposed alternatives to achieve this differentiation. This Comment analyzes those alternatives in more detail in Part III.B.

The Draft Provisions, however, do not specify what qualifies as a sacred TCE. And, unlike with other revisions of the Draft Provisions, WIPO did not include commentary explaining the revisions.19 While it may intuitively make sense that sacred TCEs should receive heightened or different protection, WIPO’s proposal to provide different levels of IP rights based roughly on a sacred/secular distinction is somewhat novel.20 It is important to think critically about what exactly justifies this higher level of protection. A clear expression of the rationale will make it easier to pitch this tiered rights system to the wider international community when the time comes for other countries to decide whether to adopt the Draft Provisions. It is also important to concede that it is not 100% clear that a novel IP protection system is even the best way to achieve the goal of protecting indigenous IP—there are reasonable arguments on both sides. This Comment avoids this discussion to jump to the discussion regarding the proposed tiered rights distinction between sacred and secular TCEs.

Section II provides necessary background in three ways. First, it defines key terms that are used throughout this Comment. Second, it describes the lead up to, and the current state of, the tiered rights proposal. Third, it provides a brief overview of general IP principles to lay a foundation for understanding the unique characteristics of TCEs, which require specialized treatment.

Section III offers various justifications why sacred TCEs should receive heightened protection, including value-based justifications, harm-based justifications, and traditional IP justifications.

Section IV summarizes and concludes the Comment.

II. Background

A. Defining Key Terms

As an initial matter, it is necessary to define “indigenous peoples,” “TCEs,” and “sacred” in detail. Defining these terms is necessary because the underlying question—should indigenous peoples’ sacred TCEs receive heightened protection?—contains these non-obvious terms. To practically implement this heightened protection, legal systems must know precisely what is receiving it. These three modifiers—“indigenous peoples,” “sacred,” and “TCEs”—answer this question.

1. Indigenous Peoples

There is no internationally accepted definition of “indigenous peoples.” The most “widely cited”21 definition, which is “regarded as an acceptable working definition by many indigenous peoples and their representative organizations,”22 comes from one of the first major U.N. studies on indigenous peoples’ issues.23 The U.N. study lists four factors that define indigenous peoples and communities.

First, indigenous peoples must “hav[e] a historical continuity with ‘pre‑invasion’ and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories.”24 Second, indigenous peoples must “consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those countries, or parts of [those countries].”25 Third, indigenous peoples must “form at present non-dominant sectors of society.”26 Fourth, indigenous peoples must be “determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identities, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural pattern, social institutions and legal systems.”27

Even though this definition has some problematic aspects,28 it appears to be the working definition for discussions regarding indigenous peoples.29 Even more relevantly, while this U.N. study definition is not incorporated into the Draft Provisions, it is cited approvingly in the WIPO Glossary of Key Terms related to Intellectual Property.30

2. Sacred

The definition of “sacred” is still not settled in the Draft Provisions context, although there have been proposed definitions.31 As of now, because “sacred” is not included in the Draft Provisions’ definition section, it does not appear that the IGC has plans to define “sacred” within the instrument. This may be because some Member States want to leave it to national legislatures to define “sacred.”32 However, the IGC does define “sacred” in its Glossary.33 The Glossary defines “sacred,” in part, as “any expression of traditional knowledge that symbolizes or pertains to religious and spiritual beliefs, practices or customs. It is used as the opposite of profane or secular, the extreme forms of which are commercially exploited forms of traditional knowledge.”34

The definition, however, recognizes that “[m]uch sacred traditional knowledge is by definition not commercialized, but some sacred objects and sites are being commercialized by religious, faith-based and spiritual communities themselves, or by outsiders to these, and for different purposes.”35 There is a slight contradiction in that this definition uses commercialization as an antonym of sacred, but then recognizes that sacred things can be commercialized. There is also a distinction between tangible objects and TCEs, but TCEs include tangible objects. Ultimately it is important to give indigenous communities the flexibility to commercialize their sacred TCEs if they choose to do so. Not doing so would exacerbate the problem WIPO is trying to solve—indigenous peoples’ lack of control over their IP. The current WIPO definition, however, would have to be revised to clarify whether commercialization negates a work’s “sacred” designation because the current definition suggests that commercialization secularizes a work.

One point of contention that will surface throughout is the tendency of some indigenous groups to reject a narrow definition of “sacred.” They argue that all of their cultural heritage is “sacred” in the sense that it is extremely important, whether explicitly connected to religion or spirituality or not.36 For example, during an IGC meeting, the representative of the Tulalip tribes objected to an earlier model of the tiered rights approach because it “focused on strong rights only in regard to secret/sacred knowledge, but this distinction did not capture the variety of ways in which [indigenous people] thought about their [TCEs].”37

3. Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs)

While “TCEs” is the current term of art used to describe tangible and intangible expressions of cultural heritage, there is a long history of different terms being used to describe these expressions. Two examples are “traditional knowledge” (TK) and “expressions of folklore” (EoF).38 Different entities use the term “TK” in different ways. Some insist that there is a distinction between TK and TCEs and that these terms should not be used interchangeably.39 Others view TK as an umbrella term under which TCEs are included.40 Within this Comment, if cited sources use the term TK it is safe to assume that the term is meant to be interchangeable with TCEs. As to the term EoF, it truly is interchangeable with TCEs, but is a more dated, anachronistic, and potentially offensive term.41 Therefore, this Comment will primarily use the term “TCEs,” but some cited sources may use EoF interchangeably.

Regarding the meaning of TCEs, the IGC is still finalizing a widely accepted definition in the Draft Provisions. The Draft Provisions propose defining TCEs as

any forms in which traditional culture practices and knowledge are expressed . . . by . . . local communities . . . in or from a traditional context, and may be dynamic and evolving and comprise verbal forms, musical forms, expressions by movement, tangible or intangible forms of expression, or combinations thereof.42

WIPO provides the following examples of TCEs that combine tangible and intangible elements: “African American quilts depicting Bible stories in appliquéd designs” and “the Mardi Gras ‘Indians’ of New Orleans who exhibit a true example of tangible (costumes, instruments, floats) and intangible (music, song, dance, chant) elements of folklore that cannot be separated.”43

B. A Crash Course in Intellectual Property Protection Justification and Structure

1. Why Protect IP

The most commonly cited IP protection justifications can be divided into four categories: (1) incentivizing creation by rewarding creativity; (2) recognizing the exclusive property right created when a person uses his own labor to improve or add value to something that originally belonged to the intellectual commons; (3) maximizing personality development, autonomy, and individual identity; and (4) fostering a just and attractive culture.44

First, IP rights incentivize creation by rewarding creativity.45 As Landes and Posner put it, “[b]ecause intellectual property is often copiable by competitors who have not borne any of the cost of creating the property, there is fear that without legal protection against copying the incentive to create intellectual property will be undermined.”46 Thus, IP generally grants a creator the (usually temporary) exclusive right to benefit from the fruits of her intellectual labor by giving her the right to control many money-making aspects of the work.47

This exclusive right is also meant to make the creator more comfortable with distributing the work to the public by giving her the assurance that she will be protected against the work’s unauthorized use. This incentive to distribute benefits society at large, which otherwise may have missed out on the work because the creator was hesitant to distribute it out of fear that it would be copied or prejudicially modified without authorization. While this justification is commonly given, Landes and Posner caution against taking it at face value because it “oversimplifies greatly,” “ignore[s] entire bodies of intellectual property law, notably trademark law,” and because it “obscure[s] the legal and economic continuity between physical and intellectual property.”48

Second, granting IP rights recognizes a property right theory proposed by John Locke. Locke posited that adding one’s labor to something that belongs to nature adds value to that thing (e.g., tilling a field to ready it for sowing).49 This increase in value transforms or improves the thing and justifies granting an exclusive property right to the improver.50 A complication with applying this theory to IP is that Locke developed it with real property in mind. While intellectual property is a form of property, Locke’s theory does not map well onto IP in the sense that “intellectual creation is a cumulative process . . . [so] it is unclear to what extent an intellectual property right can realistically be considered the exclusive fruit of its owner’s labor.”51

Third, IP rights maximize personality development, autonomy, and individual identity.52 This justification applies best to IP areas in which expression plays a key role—for example, copyright, which protects expressive works such as songs, movies, and books.53 While personality development plays an important part in American IP justifications, continental European IP systems have more robust provisions based on the personality justification. For example, there are the droit d’auteur systems in which authors are granted not only economic rights, but moral rights in which the author has: (1) the indefinite right, even after the copyright expires, to be recognized as the author of a work (the right of attribution); (2) the right to maintain creative control over a work so that a new owner can only modify the work with permission from the person who created it (the right of integrity); (3) the right to determine when a work is finished and may be disclosed to the public (the right of disclosure); (4) and the right to withdraw a work from the world (the right of withdrawal).54 These rights recognize that there is an inalienable aspect of an author’s outward expression and allow an author to maintain some level of control over the piece of their “personality” that is shared with the world.

Fourth, IP rights help foster a just and attractive culture.55 This justification is like the incentive and personality justifications, except that it focuses on collective benefits rather than individual benefits. And, while there is a normative aspect to all of the justifications listed above, this justification is particularly normative in “its willingness to deploy visions of a desirable society.”56 For example, one scholar envisions a “robust, participatory, and pluralist civil society”57 and argues that the state can help foster such a society by using copyright as a “limited proprietary entitlement through which the state deliberately and selectively employs market institutions to support a democratic society.”58 He argues that copyright serves this function in two ways. First, copyright’s productive function “encourages creative expression on a wide array of political, social, and aesthetic issues,” which “constitute vital components of a democratic civil society.”59 Second, copyright’s structural function “further[s] the democratic character of public discourse” by “foster[ing] the development of an independent sector for the creation and dissemination of original expressions . . . composed of creators and publishers who earn financial support for their activities by reaching paying audiences rather than by depending on state or elite largess.”60 Under the just and attractive culture justification, these characteristics and outcomes are weighty enough to justify IP protection.

2. Why Most Traditional IP Justifications Are a Poor Fit to Justify Protecting TCEs

While protecting some TCEs can be justified under traditional IP justifications, TCEs’ unique characteristics often require additional justifications for protecting them.

First, some commentators argue that the “incentivizing creativity” justification provides little support for TCEs’ protection. As one pair of commentators put it, “[TCEs’ IP] protection . . . cannot be defended on the basis of an incentive to innovate. The innovation has already occurred.”61 Other commentators and the communities asking for TCEs’ protection “vigorously resist” this “fixed and static” characterization62 and argue that TCEs are “dynamic and evolving.”63

A response to this counterargument is that, even recognizing that TCEs are “a living tradition,” any innovations to existing TCEs are already protected and incentivized under the current IP regime as new and unique works. Furthermore, “even if incentives to create were needed for [TCEs],” the incentives from this protection “would be quite attenuated, for both doctrinal and practical reasons.”64 Doctrinally, the criteria defining TCEs often include a requirement of intergenerational transfer, sometimes proposed at either fifty years or five generations.65 This means that a creator would not experience the benefit of his creation for at least fifty years, assuming he lived that long. Practically, “[j]ust as there is strong evidence that the furthest reaches of the life-plus-seventy-years [American] copyright term provide little or no incentive to create for rational actors,”66 it is unlikely that a promise to benefit fifty years in the future would provide much incentive to create for rational actors.67 Thus, “incentivizing creativity” offers little support for TCEs’ protection.

Another important aspect of the “incentivizing creativity” justification is the end goal of disseminating knowledge to society.68 In the case of TCEs, IP rights could encourage indigenous peoples to disseminate their knowledge to others while maintaining the ability to curtail misappropriation.69

Second, the “rewarding labor” justification also does not fit well with the practicalities of TCEs creation. Because of the intergenerational transfer requirement70 to qualify for TCEs protection, it is possible that the originator (or group of originators) is long dead by the time protection kicks in. As a pair of commentators who focus on TCEs put it, “[i]t is hard to see why [the originators’] descendants should deserve an IP right in [TCEs] that they did not originate.”71 A common response to this critique is that the individual conception of labor is incompatible with how indigenous communities view labor in relation to TCEs—namely, that a particular TCE is created and maintained by the collective labor of the community, not simply by the labor of a past individual.72 However, this brings up difficult questions of defining “the community” and describing what kind of ongoing “labor” by the community suffices to justify continuing to bestow an IP right.73

Third, unlike the first two justifications, the “personality” justification is more convincing and applicable to TCEs. In short, the “personality” justification suggests that IP deserves protection because works are an outward expression of an individual’s personality, and an individual should be able to maintain some level of control over this outward expression. As expressions of culture, TCEs are the outward manifestation of a group’s “personality.” Therefore, the group should be able to maintain control over their culture in the form of IP rights. There is, however, one logical step to take between individualized personality justifications and a collective conception of personality because the Draft Provisions propose IP protection for the benefit of a group of indigenous people, not simply for one creator within the group.74 One commentator takes this step by arguing that, so long as “the maintenance of group identity is part of the personhood interests of each individual member of the group, we do not need a theory of group rights to have personality interests count as a justification of some kind of protection of [TCEs].”75 This recognizes that “we can protect the personality interests of individuals within [a] group through protection of the group’s interests.”76

Similar to these ideas, there seems to be a school of thought that believes that culture is separable from the person or group who generated the culture. This school of thought is exemplified in a bidder’s response after he purchased sacred tribal items at auction and received backlash for doing so: “I was buying the ones that I bought to give them to a responsible museum or institution that would properly care for them because sometimes the culture that made something is not necessarily the one best to preserve it.”77 This complicates the “personality” justification because, to someone who subscribes to this school of thought, the end goal is not giving the originators IP rights over their external manifestation of their identity, but giving IP rights to the best-situated person to protect and preserve the TCE, whether that is the originating group or a museum.

Fourth, the “just and attractive culture” justification may also provide some support for TCEs protection, although perhaps not in the way it was originally conceptualized. One scholar raises moral and distributive justice considerations when justifying IP rights for TCEs. He argues that “while the concept of fairness and desert are given little attention . . . there is no question that they have been and remain powerful notions in the daily intellectual property work of courts and legislators.”78 For example, courts are willing to lean on principles of equity when deciding to consider indigenous customary law, even if they are not obligated to do so.79 He further argues that protecting TCEs would shift wealth to groups that are among the poorest and most disadvantaged in the world and would prevent a small amount of wealth from shifting away from them.80 It is also important to recognize that indigenous groups often have not, or have not been able to, avail themselves of the benefit that IP rights provide. If this were simply by choice, then there may be little room to complain. If, however, this was out of ignorance or purposeful legal disadvantage, more drastic action may be warranted to correct past wrongs—in this case, protecting IP that traditionally is outside of protection scope. If a “just and attractive” culture is one in which wealth is more equally distributed and past wrongs are remedied, then IP protection for TCEs seems to be one way to achieve this kind of culture.

3. The Ways in Which the IP Protection System Currently Differentiates Granted Rights

The Draft Provisions’ proposed rights are notable because, at their height, they offer a sacred TCE’s owner every protective right, blurring the distinction between copyright, trademark, and trade secrets, and blurring the distinction between differing levels of protection within copyright, trademark, and trade secrets.

The Draft Provisions propose differentiating protection scope along lines of secretness, sacredness, and restriction. Secretness and restriction are not quite as novel as sacredness. For example, the law of trade secrets is internationally accepted and protects information that entities work to keep secret.81 However, sacredness as a differentiating factor is quite foreign to the current IP system’s way of differentiating IP protection scope. Current IP law grants different protection durations to different IP areas, and grants different exclusionary rights between, and even within, different IP areas.

For example, in terms of time, the international minimum term for copyright protection, set by the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement, is the life of the author plus fifty years.82 For trademarks, the initial term is a minimum of seven years, with the ability to renew indefinitely by paying renewal fees and keeping the mark in use.83 By doing this, IP law seems to assume that a trademark holder will have a general sense of the value she will be able to extract from a mark during a particular term. This incentivizes her to renew the trademark only if the expected benefit is greater than the cost of renewal. If it is not, trademark law is set up so that the trademark holder will be incentivized to not renew the mark and release it so that another entity that might generate more value using the mark can do so. For trade secrets, the term is unlimited so long as the information: (1) is secret in the sense that it is not generally known among or readily accessible to persons within the circles that normally deal with the kind of information in question; (2) has commercial value because it is secret; and (3) has been subject to reasonable steps under the circumstances by the person lawfully in control of the information, to keep it secret.84

This differentiation of protection term is notable because a tension point in the TCEs protection discussion is whether TCEs should be granted indefinite protection. Some argue that indefinite protection is the only way to satisfactorily protect TCEs,85 while others argue against indefinite protection, citing the importance of the public domain.86 The bigger problem, however, is that TCEs, do not fit neatly within recognized IP areas, so it is difficult to speak of TCEs receiving indefinite protection as a whole, even if particular TCEs can be categorized as trademarks and trade secrets and receive indefinite protection.87

In terms of rights granted, copyright entitlements can be broken down into two categories: economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights “allow authors to extract economic value from the utilization of their works,”88 while moral rights “allow authors to claim authorship and protect their integrity.”89 Trademark law makes a distinction between the rights that it grants to owners of marks and the enhanced rights it grants to owners of well-known marks. To all owners, trademark grants the right to “prevent all third parties not having the owner’s consent from using in the course of trade identical or similar signs for goods or services identical or similar to those in respect of which the trademark is registered where such use would result in a likelihood of confusion.”90 For example, if an entity registers the trademark “VitalProtect” for surgical instruments and another entity registers the same trademark for mobile phone cases, there would likely be no violation of the trademark; although the entities are using identical trademarks, they are not being used for identical or similar services, minimizing the likelihood of consumer confusion. Conversely, for well-known marks, trademark protects “against use of the mark on non-similar goods or services.”91 For example, suppose that surgical instrument “VitalProtect” is a well-known mark. This could prevent the mobile-phone-case-selling entity from registering or using the “VitalProtect” trademark if a court found that the surgical instrument entity’s “interests are likely to be damaged by such use.”92 Regarding trade secrets, international IP law protects them against “the unauthorized acquisition, use or disclosure of such secret information in a manner contrary to honest commercial practices by others.”93

C. WIPO’s Tiered Rights Proposal

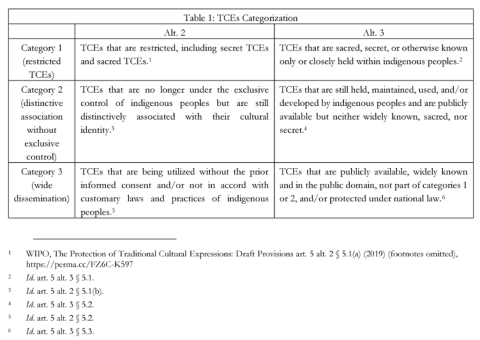

There are currently two proposed alternatives for a tiered rights approach, Alternative 2 (Alt. 2) and Alternative 3 (Alt. 3), 94 both found within Article 5 of the Draft Provisions.95 Given that the Draft Provisions are by definition still in the draft stage, WIPO’s strategy seems to be laying out all of the serious options, typically ranging from giving the most deference to states to the least deference. The two proposed alternatives are similar in that they both classify TCEs into three categories and then construct a tiered system of protection and rights based on the different categories. Table 1 below shows the way that Alt. 2 and Alt. 3 categorize TCEs.

Turning first to Cat. 1, Alt. 2 and Alt. 3 are similar in the scope of TCEs they protect. Both protect sacred and secret TCEs. Across both alternatives, Cat. 1 can be categorized as restricted TCEs. From here, the alternatives have semantic and substantive differences. In Cat. 2, both alternatives envision distinctive association without exclusive control. In Cat. 3, both alternatives describe wide dissemination. Notably, however, both Alt. 2 and Alt. 3 place widely disseminated sacred TCEs into Cat. 1, treating them as, and giving them the protection of, restricted TCEs. This is notable because, as Table 2 below shows, Cat. 3 seems to recognize that when works are widely disseminated, creators should receive fewer exclusive rights. This is likely because of the practical impossibility of trying to claw back something that is already woven into a society’s corpus of creative works and because of the difficulty of determining TCEs’ authorship. Notwithstanding this, the Draft Provisions seem to give much weight to a work’s sacred nature such that they seem to propose treating widely disseminated sacred TCEs differently from widely disseminated secular TCEs.

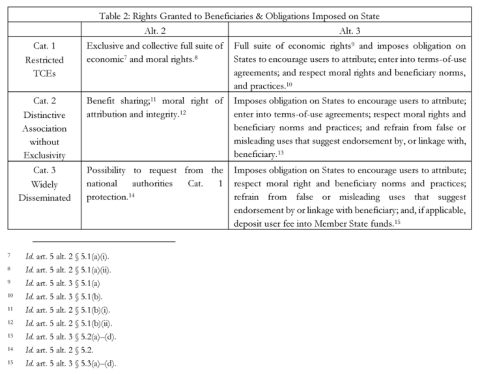

Both alternatives grant different levels of protection to beneficiaries, but Alt. 2 also imposes obligations on states. The alternatives use the term “beneficiaries” to refer to indigenous because they propose a system in which indigenous peoples do not hold IP rights themselves, but instead are beneficiaries under a model in which the State holds the TCEs right and administers it in conjunction with the indigenous community that originated the TCE.96 Table 2 below shows the rights granted and obligations imposed under Alt. 2 and Alt. 3.

Comparing Cat. 1 across both alternatives, the most dramatic difference is that, while Alt. 2 grants beneficiaries moral rights, Alt. 3 gives states the tepid obligation to “encourage” users of TCEs to do everything that moral rights would grant. Furthermore, for Alt. 3, Cat. 1 is the only category that actually grants the beneficiaries any rights. Alt. 3 Cat. 2 and 3 only impose upon states the obligation to encourage users to do almost identical things, except that Alt. 3 Cat. 3 adds the encouragement to participate in a sort of compulsory licensing system in which the user pays a fee for using the work regardless of if it is in the public domain and typically available for use by anyone for free. Alt. 2 Cat. 2 provides a potentially similar benefit-sharing model, although it does not specify how the benefit sharing system would be administered.97 Alt. 2 Cat. 3 imposes a potentially powerful protection scheme similar to Alt. 2 Cat. 1 (full suite of economic and moral rights).

The caveat is that beneficiaries are not entitled to this protection. They are simply permitted to request it. For countries friendly to their indigenous peoples, this provision could effectively extend the full suite of economic and moral rights to all TCEs, regardless of their restricted or unrestricted nature, so long as the TCEs were being used without indigenous peoples’ prior informed consent and contrary to their customs and practices. This is certainly a flexible provision, but if it is used, it effectively negates any distinction made between widely available and restricted TCEs based on the discretion of whatever national authority hears these petitions. While this certainly addresses the concerns of some indigenous communities that TCEs should be given the highest level of protection regardless of the secular/sacred distinction, it also turns what is intended to be a precise instrument into a blunt instrument. It is unlikely that skeptical countries would be on board with this expansive grant.

III. Potential Justifications for Heightened IP Protection for Sacred TCEs

To this point, this Comment has laid out the problem of misappropriation of indigenous group’s TCEs and the particularly troubling aspects of misappropriation of sacred TCEs. It then described the ways stakeholders define the terms “sacred,” “indigenous,” and “TCEs” to narrow the scope of the conversation. It then laid out some traditional justifications for IP protection, pointed out the poor fit of these justifications as applied to protection of TCEs, and discussed the ways that IP regimes differentiate the grant of rights between and within IP areas. This all led to a discussion of WIPO’s Draft Provisions, which propose differentiating rights based on the sacred versus secular distinction.

Current international IP does not confront head on the secular versus sacred distinction, probably due in part to nations’ different approaches to freedom of expression, attitudes toward regulation of sacred things, and the political power (or lack thereof) of indigenous groups. Assuming that this distinction is one that should be built into international IP law, it is essential to convince as many nations as possible (or at least a critical mass of nations that heavily influence international intellectual property policy) to adopt WIPO’s proposed system. To do this, it is helpful to consider the most promising justifications to see if they hold up under scrutiny.

A. Traditional IP Justifications

While many traditional IP justifications may be a poor fit for justifying TCEs protection in general, it is still worth applying them to sacred TCEs to lay out the nuances that arise.

1. Incentivizing Creativity and Distribution

There are two versions of the incentivizing creativity justification, neither of which lend much support to sacred TCEs. The first version is that protecting sacred TCEs would incentivize creation by giving the creators the right to make money from their works without fear of copycats or free riders.98 This fits poorly when applied to sacred TCEs because while some indigenous peoples do choose to commodify their sacred TCEs, the vast majority do not.99 The second version is that protecting sacred TCEs would give creators peace of mind to share their work with society because they know that they will maintain some level of control over it.100 This explanation is also not well-suited to sacred TCEs. In fact, granting sacred TCEs exclusive IP rights may deter dissemination even more than the status quo.101 These arguments, however, typically focus on market dissemination.102 A broader view of dissemination, namely educational or nonprofit dissemination, gives this justification slightly more weight. An indigenous community may be more willing to let researchers observe or document their sacred ceremonies if the community knows that the researcher can only use the information for educational purposes. The trouble with this explanation is that this educational use is already allowed under fair use doctrine, and this would not change under the Draft Provisions because they also envision fair use exceptions.103 In other words, protecting sacred TCEs under the Draft Articles would have little effect on an indigenous group’s willingness to allow educational use because educational use is already allowed. The only effect it may have is to allay a group’s distrust that researchers would lie about only using their TCEs for educational use because the indigenous groups would know that there would be new penalties for commercializing without permission.

2. Rewarding Labor

The “rewarding labor” justification104 provides little support for protecting sacred TCEs for the same reasons that it provides little support for protecting TCEs generally. Sacred TCEs in particular are often considered to be the product of a community’s collective labor, not one individual’s creative labor.105 This justification is further complicated when considering the practical necessity of lowering transaction costs by having a clear procedure for approving or licensing use of a sacred TCE. For example, the Australian case of Yumbulul v. Reserve Bank of Australia106 came about because an aboriginal artist, Yumbulul, had granted the Reserve Bank of Australia permission to depict on a ten dollar note one of his sculptures which was used for religious ceremonies.107 However, Yumbulul later claimed that he only had “authority within his own clan to paint certain sacred designs”108 but in order to sell the design, he needed to “make sure that the clan people involved, that is, the traditional owners and managers of the rights to the pole and the ceremony, knew what he was doing.”109 This example clashes with the “rewarding labor” justification, “which clearly would recognize the right of an individual (because he is the originator and hence the one who should be rewarded) to give such consent.”110

3. Personality, Autonomy, and Individual Identity

The “personality” justification111 is one of the more convincing of the traditional IP justifications as applied to sacred TCEs. Because a culture’s sacred TCEs are so integral to its expression of its “personality,” protecting sacred TCEs in particular would protect the group’s personality interests and help preserve the culture itself. Even focusing on the individual rather than the group, individuals within indigenous communities lose an opportunity to have an accurate view of their individual identity within the group when sacred TCEs are appropriated to the point of losing significance.112

4. Developing a Just and Attractive Society

The “just and attractive society” justification also lends some support to IP rights in sacred TCEs. There are two angles from which to view this justification—a diverse society is an attractive society, and a just society is one in which past wrongs are remedied. Turning to an attractive and diverse society, and closely related to cultural extinction harms,113 in order to maintain a diverse society it is important to give groups the ability to preserve cultural distinctions— here in the form of IP rights. Turning to past wrongs, it is no secret that States have often engaged in “assimilationist policies,”114 including “wide suppression of Indigenous languages and religions.”115 And “[p]atterns of expropriation of Indigenous religious and cultural objects and neglect, even destruction of Indigenous cultural manifestations, unfortunately still continue.”116 Even though Indigenous freedom of religion rights are manifested in various instruments of international law,117 “[t]he right to religion has so far been of limited use to Indigenous peoples, mainly because of its recognition as an individual right in international law.”118 To fill this gap, “national case law has been heavily reliant on the right to property or even intellectual property rights for the protection of manifestations of the Indigenous spiritual beliefs.”119 An international recognition of IP rights in sacred TCEs would help develop a more effective system to protect indigenous religion, a necessity given States’ historic assimilationist and suppressionist tendencies.

B. Value-Based Justifications

Another category of justifications focuses on the value of sacred TCEs. Under this view, sacred TCEs should receive more protection than secular TCEs because sacred TCEs are more valuable, either economically or otherwise. As will be discussed below, this idea is not foreign to IP right differentiation in current IP systems and could justify the Draft Provisions’ tiered rights protection scheme.

1. Economic Value

One possibility is that sacred TCEs should receive more protection than non-sacred TCEs because sacred TCEs have greater economic value than non‑sacred TCEs. To test this theory, it is necessary to answer three questions: (1) do people in fact pay more for sacred TCEs than non-sacred TCEs?; (2) if so, do they pay more because the TCEs are sacred?; and (3) if the answers to questions (1) and (2) are yes (suggesting that sacred TCEs have higher economic value because they are sacred), does this justify heightened IP protection for sacred TCEs?

First, do people in fact pay more for sacred TCEs than non-sacred TCEs? This apparently straightforward question does not have a straightforward answer. Perhaps the most obvious setting in which to analyze economic value of sacred versus secular tangible TCEs is the artifacts auction market. While this market deals only with tangible TCEs, it may give clues or serve as a proxy for intangible TCEs. Unfortunately, an empirical study on this topic has not been conducted. One source argues that “generally, antiques of a highly religious nature, especially Catholic and other Christian articles, have a much lower value than articles with similar attributes having no religious attachment.”120 It gives the following examples: while an 18th century book on surgical procedures, astronomy, or global exploration might be sold for over $1,000, an 18th century bible will frequently sell for less than $150.121 Likewise, while a 1910 Santa Claus postcard in like-new condition might be sold for between $5 to $10, an equally high-quality postcard of equal quality depicting angels will usually fetch less than $1.122 This information, however, is not a perfect fit for the question presented given that it is listed on an appraiser’s blog, does not appear to be peer-reviewed or based on a study, and focuses on Christianity, a dominant religion unlikely to qualify for protection reserved for “indigenous peoples.”123 Another source that lists the ten most expensive antiques ever sold at auction does not include any sacred items.124 Based on the crude available data, it appears that sacred TCEs do not in fact have higher economic value than secular TCEs, but an empirical study is required before drawing meaningful conclusions.

Assuming for the sake of argument that sacred TCEs do in fact have higher economic value than secular TCEs, is this because of their sacredness? Again, the answer is unclear, but perhaps the closest to a satisfying answer is that it depends on the buyer, especially in the auction context. As an illustration, in 2013, a French auction house auctioned dozens of Hopi tribal masks after defeating a legal challenge to stop the sale.125 An American buyer of two of the masks said the following after returning the masks to the Hopi following backlash for his purchase: “I was buying the ones that I bought to give them to a responsible museum or institution that would properly care for them because sometimes the culture that made something is not necessarily the one best to preserve it. I did not know that they were sacred.”126 After interviewing the buyer, the Atlantic reported that “[he] had little idea of the items’ history, or of the controversy around them. Of his impulsive buy, he simply thought they were gorgeous” and that “[he] had never seen such things.”127 This suggests that some collectors do not consider the sacredness of an object; they simply consider its perceived aesthetic value or, as one scholar suggests, its value as “cultural capital,” a term used to describe the tendency to seek out cultural experiences to “add cosmopolitan luster” to one’s life.128

As a counterexample, a devout believer of a particular faith may be willing to pay significantly more for artifacts related to her faith. An example of this is the Green family, the owners of Hobby Lobby, spending millions of dollars on pillaged Christian artifacts, for which it eventually paid a settlement.129 Not only was the Green family willing to pay the upfront costs of purchasing the artifacts, but, assuming that the Green family knew that the artifacts were pillaged, they were also willing to run the risk of paying the additional penalties that could arise.

Complicating this example is the Hopis’ refusal to bid on Hopi items at auction in order to recover them.130 This refusal suggests that it is possible to value an item either so highly or in such a way that bidding on it at auction would be repulsive. It is likely that this was a moral position in protest of the masks’ auction in general, but a purely economic view would predict that the Hopi would be willing to pay anything to recover the masks that they valued so highly.

Assuming for the sake of argument that the answers are yes to questions one and two, and sacred TCEs do in fact have more market value because they are sacred, does this justify a heighted IP protection for TCEs? While there are arguments for both sides, it seems like the answer could plausibly be yes.

First, one could argue that higher market value due to sacred nature does not justify heightened IP protection. Perhaps the best argument for this is that IP law should not bear the cost of differentiating protection based on information that others are in the best position to have and costs that others are in a better position to bear. For example, a person may buy a $200 safe to store a $1,000 “idea” but may buy a $2,000 safe to store a $10,000 “idea.” The owner of the idea is in the best position to determine, or to have someone determine, how much the idea is worth and to determine what level of protection is worth paying for. Granted, it would be inefficient for him to overprotect the idea by paying far more to protect it than what it is worth. IP law, however, would still provide some base level of protection for all ideas, regardless of worth, so the owner would not bear 100% of the protection cost, just the marginal cost based on the difference between the item’s value and the base protection. To give a concrete example, if the government provided a $200 stipend for buying a jewelry safe, the necklace’s owner would have to decide whether he was comfortable buying a $200 safe, or whether he would use those $200 dollars to help pay for a more expensive safe and pay the price difference himself. This would be more efficient than asking a government inspector to tailor the jewelry safe stipend based on an investigation of every person’s jewelry situation. People would pay for the level of protection and take the precautions that they believed their jewelry was worth. This example echoes the criticism to which the Tulalip representative in Section I was responding—namely, that if the Pueblo people did not want their ceremony photographed, they should have covered their kiva.131

The problem with this argument is that the law already provides tiers based on value in many contexts. For example, in the larceny context, the law tiers penalties based on the stolen items’ value. To be fair, this is not a perfect analog to the sacred TCEs tiered system because, in the larceny context, penalties are tiered, not the owner’s rights. The Draft Provisions do not propose higher penalties for infringing sacred TCEs’ rights. However, the concept of tiered rights and penalties are not as novel in the law as some try to make them out to be.

Another example is in the trademark context, which provides a plausible argument that higher market value due to sacred nature does justify heightened IP protection. IP law distinguishes between marks and well-known marks and grants more protection in the form of enhanced exclusionary rights to owners of well‑known marks.132 This addresses a fraud problem unique to well-known marks in which the user of a conflicting mark benefits from the value of the well-known mark by passing off counterfeit goods as authentic, higher value goods.133 Sacred TCEs may also suffer from this problem. If they are more valuable because of their sacred nature (i.e., if a fraudster would see an opportunity to make more money by falsely claiming that a product is sacred than he would make if he advertised the product as secular) it would make sense to offer sacred TCEs more protection.

The problem with this argument is that it is unclear whether sacred TCEs have more market value than secular TCEs. In fact, cursory evidence suggests that they do not. If sacred TCEs did have more market value, this would be a strong argument for heightened protection. The irony, however, is that this argument most aligns with the current IP system’s values but is most misaligned with many indigenous peoples’ values regarding their sacred TCEs. For example, in the French auction house Hopi mask case, the court either did not or could not consider the Hopi’s testimony that “such [sacred] objects would never be given away or sold.”134 This testimony clashes with the idea of granting IP protection to allow distribution on the author’s terms for his and society’s benefit135 because some indigenous peoples would not distribute a work regardless of the level of protection offered.

2. Religious Value

Of course, economic analysis is not the only way to value IP, although it is the method most in line with how the current IP system is often analyzed. Sacred TCEs have religious value that is much more difficult to calculate, perhaps only for practitioners, perhaps in general. International law does recognize religious value, but it is typically applied to sacred objects and spaces. One scholar has argued that the right to protect indigenous sacred physical spaces can flow from the international right to freedom of religion or belief.136 With a few logical steps, this analysis can be extended as a justification for protecting nontangible sacred TCEs. The argument proceeds in this way. The right to freedom of religion or belief incorporates protection for worship.137 The protection of worship includes protection of the place of worship.138 Although this does not necessarily mean that a place deemed holy or sacred will automatically receive protection as a sacred space under the human right to freedom of religion or belief, the right to freedom of religion or belief protects actions specifically demanded by the religion pursuant to the doctrine and edicts imposed on believers.139 So, if the religion demands worship at a particular place, then that place should be protected under the freedom of religion and belief. While this argument may be convincing as applied to sacred spaces, intangible sacred TCEs in this context are distinct in one important way: While the right to freedom of religion and belief protects against infringing government action, protecting sacred intangible TCEs requires shielding them from infringing private action. This may not be an insurmountable obstacle. The framework for the protection of religion is already laid out, and the Draft Provisions are attempting to create a new system of protection, not argue for rights within the current system. Signaling the connection to freedom to practice religious rites and ceremonies free from government interference may provide a good jumping-off point for discussions of freedom to practice free from private interference.

C. Harm-Based Justifications

Perhaps the flip side of value-based justifications is harm-based justifications. Rather than considering the value of the protected items, it considers the harm that would result from a lack of protection. Four types of harm considered here are devaluation, cultural extinction, feeling offended, and desecration.

1. Devaluation

Devaluation is used broadly here to describe devaluation, economic or otherwise. In the Hopi mask case,140 the sacred masks were arguably devalued economically and intrinsically when the judge considered only their aesthetic qualities as art, rather than their sacred value.141 In this case, the judge either would not or could not consider the Hopi people’s understanding of their sacred objects and redefined the masks to fit preexisting legal categories, namely aesthetic cultural objects that have little restrictions on their sale. This case in particular may “signal that it is all right for future courts to reevaluate the worth of an object on standards that are not necessarily in line with its true value.”142

One scholar describes the devaluation that occurs when TCEs are misappropriated as “depreciative commodification,”143 a problem to which “cultural products of religious or spiritual significance are particularly susceptible.”144 Another scholar connects a similar phenomenon to the “arrival of a global commercial culture,” which “brings the all-too-common de-culturization of traditional customs, rituals and folklore in order to allow their streamlining for mass consumption.”145 She gives the example of “tourists in New Zealand watch[ing] performers clad in bastardized versions of ‘traditional’ Maori dress perform[ing] a welcoming ceremony although the performers have no concept of, or appreciation for, the cultural significance of such rituals.”146 Thus, it is important to recognize that while some cultural products may “retain their internal cultural value despite external appropriation,” others “may lose significance altogether.”147 Giving indigenous peoples enhanced protection and greater control over their sacred TCEs would allow them the flexibility to make those determinations themselves. Just as there are indigenous peoples that would never dream of commodifying their sacred TCEs,148 there are some indigenous peoples that are already commodifying their sacred TCEs.149 The proposed tiered rights system is beneficial because it puts into indigenous peoples’ hands the power to decide which sacred TCEs would retain their value if commodified and which would not.

2. Cultural Extinction

For some indigenous peoples, the ability to protect and control their sacred TCEs is more than a matter of value or control—it is a matter of their cultural survival.150 Regarding TCEs generally, the fear of cultural extinction is particularly applicable to indigenous peoples because of “the existence of ongoing threats to their continued existence” in the form of attempted eradication and forced assimilation. 151 TCEs play a crucial role in culture because, in many cases, those cultural expressions are what help a culture “identify itself as unique and separate.”152 Without TCEs, an indigenous group’s sense of identity would be negatively affected, and the culture itself may be lost.153

It is unlikely, however, that IP rights alone would stem the loss of indigenous culture. To be sure, there are some international instruments that independently provide a legal, albeit nonbinding, backdrop of protection, such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)154 which recognizes indigenous peoples’ right to “maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions”155 and the right to “maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions.”156 There are, however, other ways that indigenous groups’ sense of identity is lost such as by forced or voluntary assimilation and cultural appropriation, either by the indigenous group assimilating into the dominant culture, or by the dominant culture appropriating the indigenous group’s knowledge.157 IP rights may help protect against the latter, but they would not protect against the former.

Regarding sacred TCEs specifically, “[t]he loss of cultural heritage is a tragedy for those peoples and communities that depend upon the integrity of their knowledge and cultural systems for their survival.”158 This argument, however, needs to be further developed because it presupposes that cultural heritage can be “lost.” Loss is much easier to conceptualize when it is applied to tangible objects, but it is not as obvious when considering intangible objects. Further skepticism is raised when considering the argument that IP is non-rivalrous, meaning that IP, unlike tangible goods, is not diminished by its use and “can be used by many individuals concurrently.”159 Thus it may be difficult to see how other people copying or selling sacred intangible TCEs could be described as taking those intangible TCEs away from indigenous peoples, resulting in the indigenous peoples “losing” that piece of cultural heritage. However, Landes and Posner argue that the non-rivalrous nature of IP is often overstated, “if only because it ignores the trademark and right-of-publicity cases that recognize that intellectual property can be diminished by consumption.”160

To be fair, diminishment or dilution is not exactly analogous to loss unless the diminishment continues until nothing is left. It is possible, however, in extreme circumstances for diminishment to lead to there being nothing left. For example, in cases of misappropriation, one scholar argues that “[t]he cultural value or message embedded in the product may be diluted or eliminated; in the extreme, public identification of the source community through the cultural product may disappear altogether as the item becomes generic.”161 In addition, she argues that, “[d]epending on the nature of the tradition, and the type and pervasiveness of misappropriation over time, the community may even abandon the cultural product altogether and thus lose a medium for expression of its beliefs and values.”162 Extending the argument, continued loss of distinctive cultural practices could even result in losing “indigenous” status given that, while there is no standard definition of “indigenous,” all of the widely cited definitions contain some requirement of distinctiveness from the dominant society.163 Furthermore, under Alt. 2 Cat. 2 of the Draft Provisions, loss of distinctive association with an indigenous group would drastically affect the level of protection offered to the TCEs.164

There is, however, a complication that needs to be addressed in this argument. Abandoning a practice may result in “losing” it, but abandonment opens the door to arguments that abandonment is a choice—one made under pressure, but a choice nonetheless. This weighs against granting greater protection. This phenomenon has parallels in the real property doctrines of adverse possession and abandonment. For example, “[s]ometimes an intention to abandon property can be inferred from negligence in the use of it.”165 The possessor “implies by his conduct that the property is not worth much to him and creates the impression among potential finders that the property has indeed been abandoned and is therefore fair game.”166 Invoking abandonment “becomes a method of reducing transaction costs and increasing the likelihood that the property will be shifted to a more valuable use.”167 While “[t]he doctrine of adverse possession is rarely if ever invoked in intellectual property cases,” something similar operates in the trademark and trade secret arenas. For example, in trade secret law, if a possessor of the trade secret fails to take precautions to keep his invention secret, the law presumes that he does not value it highly and the possessor loses legal protection.168 The Draft Provisions will have to address these ideas engrained in real property and IP law. One way to do so is to consider customary law when thinking about the ideas of negligent use and failing to take precautions.

3. Being Offended

A concept that often arises when indigenous people describe the harm caused by the appropriation of their TCEs is feeling offended. For example, in WIPO’s Consolidated Analysis of the Legal Protection of TCEs, WIPO writes that “[i]ndigenous, local and other cultural communities have complained that their cultural expressions and representations are used without authority in disrespectful and inappropriate ways, causing cultural offense and harm.”169 Some people may discount the harm of offense because of its subjective nature.170 The subjective element also makes it difficult to effectively protect against.171 The harm of offense, however, takes on greater importance when it is recognized as a way of describing the “felt aspects of assaults on dignity.”172

The concept of dignity, while still containing subjective elements,173 has some grounding in international instruments and law.174 For example, UNDRIP provides that “the rights recognized herein constitute the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”175 Similarly, the Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”176

Dignity considerations shed light on why exactly indigenous people feel offended when outsiders misappropriate their TCEs, particularly their sacred TCEs. Indigenous creativity has long been seen as a well from which to draw, considering only the end benefit of drawing from the well and not the detriment this could bring to the community. This way of thinking undermines the dignity of indigenous peoples.

A related concept is the harm to mental health that losing sacred sites brings an indigenous group. One scholar points to a pair of Canadian environmental risk assessments which conclude that proposed developments should be rejected because indigenous communities would suffer mental and psychological harm from losing their sacred sites or having them altered.177 Emotional trauma and distress is often ignored in rational decision making.178 However, when conducting its cost-benefit analysis, the Canadian federal impact-assessment panel “made a finding that the collective experience of emotional trauma was an indicator of mental distress that had a community‑wide effect.”179 Based on this finding, the panel identified mental health as “a component of loss” which could be appropriately “compared with beneficial impacts.”180 While this study did not specifically discuss feeling offended, it connects to feelings of offense by acknowledging mental impacts as appropriate considerations when making decisions that affect an indigenous group’s cultural heritage, especially when it is sacred.

4. Desecration

Sacred objects are particularly vulnerable to desecration.181 The concept of prohibiting desecration is not novel in the international context, though perhaps it is not always called “desecration.” For example, many international law instruments prohibit the “mutilation” or “despoliation” of dead bodies during armed conflicts.182 Other instruments prohibit attacks against “cultural property,” a term which includes “works of art or places of worship which constitute the cultural or spiritual heritage of people.”183 These examples have limited ability to extend to the TCEs context for two reasons. First, these prohibitions only apply during armed conflict. The rationale for this selective application is unclear, but it may have to do with the instinct to clearly spell out what constitutes war crimes. Second, these instruments only apply to tangible objects (i.e., bodies, buildings, and other tangible objects). This is likely because it is much easier to conceptualize what it means to desecrate a tangible object than an intangible one.

Thus, there are three major obstacles to using anti-desecration considerations as a justification for heightened protection for sacred TCEs. First, WIPO would have to justify extending anti-desecration protections outside of the sphere of armed conflict at the international level. Second, WIPO would have to explain how to conceptualize the desecration of intangible expressions, such as dances or ceremonies, which cannot be destroyed or mutilated in the same way as tangible objects.

Yet another issue is that WIPO would also have to confront the tension between protection against desecration and freedom of speech concerns.184 For example, consider the controversial “Piss Christ” photograph, which depicts a crucifix submerged in the photographer’s urine.185 This photograph sparked a controversy pitting freedom of expression versus others’ interest in curbing what they saw as blasphemous.186 In this case, there is an aspect of mitigation given the historic dominance of the religion that the photograph commented on. Consider, however, instead of a crucifix submerged in urine, a Native American sacred ceremonial headdress submerged in urine. This seems to raise even stronger feelings of distaste, of perhaps kicking someone who is down. Presumably, this would violate WIPO’s Draft Provisions, particularly the moral rights provisions, and would be actionable. This, however, conflicts with perhaps uniquely American, perhaps more widely held, notions of freedom of expression. This issue is not easily resolved and must be carefully considered in WIPO’s discussions.

IV. Conclusion

WIPO’s work to protect indigenous culture generally has been long in the making and is long overdue. It is important to balance an effective legal instrument that will effectively meet policy goals with creating a legal instrument that can be justified enough that it will achieve widespread adoption. WIPO’s proposal to provide heightened protection to sacred TCEs is a particularly novel proposal, and as a novel proposal, it is open to criticism and in danger of rejection due to fear of change. WIPO must have well-developed justifications as to why sacred TCEs deserve heightened protection. These justifications may be framed as value-based or harm-based, but they must be grounded in terms that the international community is used to and will accept. It will also be important to balance the tension between over-defining terms and having a vague instrument. On the one hand, the term “sacred” is susceptible to endless debates about its definition, resulting in nothing getting done. On the other hand, it is important to provide clarity as to what exactly is being granted protection. The goal of international protection for indigenous IP is important and worth pursuing.

- 1It is important to clarify how this Comment uses the word “misappropriation.” Misappropriation’s root word is appropriation, which “at its most basic . . . means to take something that belongs to someone else for one’s own use.” Intell. Prop. Issues Cultural Heritage Project, Think Before You Appropriate: Things to Know and Questions to Ask in Order to Avoid Misappropriating Indigenous Cultures 2 (2016), https://perma.cc/MC5D-T3AT [hereinafter Think Before You Appropriate]. In the heritage context, “appropriation happens when a cultural element is taken from its cultural context and used in another.” Id. Based on this definition, appropriation happens frequently, “as people and cultures exchange things and borrow ideas from each other all the time to create new art forms, technology, and symbolic expression.” Id. This Comment does not advocate for completely doing away with appropriation as it recognizes the importance of a robust public domain and a vibrant marketplace of ideas, concepts which contribute to cultural and artistic development. A related but distinct concept is misappropriation. Misappropriation “describes a one-sided process where one entity benefits from another group’s culture without permission and without giving something in return.” Id. at 3; see also Christine Haight Farley, Protecting Folklore of Indigenous Peoples: Is Intellectual Property the Answer, 30 Conn. L. Rev. 1, 8 (1997) (“For [ ] marketers, Aboriginal culture is merely a commodity, there to be strip-mined for commercial profits.”). Misappropriation is particularly detrimental when it involves “intentionally or unintentionally harming a group through misrepresentation or disrespect of their culture and beliefs.” Think Before You Appropriate at 3. It “can also entail considerable economic harm when it leads to profiting from the use of a cultural expression that is vital to the wellbeing and livelihood of the people who created it.” Id. This definition of misappropriation is different than the one proposed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). WIPO situates “misappropriation” within the common-law unfair competition tort of misappropriation. Based on this positioning, WIPO defines misappropriation as “the common-law tort of using the non‑copyrightable information or ideas that an organization collects and disseminates for a profit to compete unfairly against that organization, or copying a work whose creator has not yet claimed or been granted exclusive rights in the work,” citing Black’s Law Dictionary. Intergovernmental Comm. on Intell. Prop. and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore [IGC], Glossary of Key Terms Related to Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions, Annex, at 30, WIPO/GRTKF/IC/40/INF/7 (2019) [hereinafter WIPO 2019 Glossary].

- 2IGC, Report of the Twenty-Seventh Session, ¶ 62, WIPO Doc. WIPO/GRTFK/IC/27/10 (July 2, 2014), https://perma.cc/U24X-TCWM [hereinafter IGC 2014 Report].

- 3A kiva is a subterranean ceremonial room with no roof. Kiva, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://perma.cc/WML7-AXQ5.

- 4See Susan Scafidi, Who Owns Culture?: Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law 103 (2005).

- 5IGC 2014 Report, supra note 2, ¶ 66.

- 6Id.

- 7Id.

- 8Id.

- 9Id. ¶ 81.

- 10The first discussions of a tiered system were held at the 2014 Bali Consultative Meeting. IGC, Report of the Thirty-First Session, ¶ 22, WIPO Doc. WIPO/GRTFK/IC/31/10 (Nov. 28, 2016), https://perma.cc/AZH4-9JV9 [hereinafter IGC Nov. 2016 Report].

- 11See About WIPO, World Intell. Prop. Org., https://perma.cc/8TQQ-DN8F.

- 12See id.

- 13Draft Provisions/Articles for the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions, and IP & Genetic Resources, World Intell. Prop. Org., https://perma.cc/6D6U-E5W2.

- 14See IGC 2014 Report, supra note 2, ¶¶ 22–66.

- 15Copyright law generally protects works of artistic, literary, and musical expression, including books, cinematographic works, paintings, sculpture, photographic works, pantomime, and, more recently, computer software programs and databases. See, e.g., Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Sept. 9, 1886, as revised July 14, 1967, art. 2, 828 U.N.T.S. 221, 227 [hereinafter Berne Convention] (defining copyrightable subject matter as “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression”). Doris Estelle Long, The Impact of Foreign Investment on Indigenous Culture: An Intellectual Property Perspective, 23 N.C.J. Int’l L. & Com. Reg. 229, 233 n.8 (1997).

- 16Trademark law generally protects corporate symbols, logos, and other distinctive indicia of the origin of goods or services. See, e.g., Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Including Trade in Counterfeit Goods, art. 15, Apr. 15, 1994, 33 I.L.M. 81 [hereinafter TRIPS] (defining a trademark as “any sign or any combination of signs, capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings”). Long, supra note 15, at 233 n.9.

- 17Trade secret law generally protects confidential information that has commercial value due to its secret nature and that has been the subject of reasonable steps by the person lawfully in control of the information to keep it secret. See, e.g., TRIPS, art. 39 (defining as “secret” protected confidential information having “commercial value because it is secret” and having been subject to “reasonable steps” to keep it “secret”). Long, supra note 15, at 233 n.10.

- 18See Justin Hughes, Traditional Knowledge, Cultural Expression, and the Siren’s Call of Property, 49 San Diego L. Rev. 1215, 1239–40 (2012); Cultural Law: International, Comparative, and Indigenous 617 (James A. R. Nafziger et al. eds., 2010) (citing Christoph Antons, Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Property Rights in Australia and Southeast Asia, in New Frontiers of Intellectual Property Law 37, 40–41 (Christopher Heath & Anselm Kamperman eds., 2008)).

- 19For an example of the commentary sometimes included with new iterations of the Draft Provisions, see IGC, The Protection of Traditional Cultural Expressions: Draft Articles, Annex, at 4, WIPO/GRTFK/IC/22/4 (2012).

- 20See IGC Nov. 2016 Report, supra note 10, ¶ 142; Laura Booth, Spirits Up for Sale: Advocating for the Adoption of Ethical Guidelines to Govern the Treatment of Sacred Objects by Auction Houses, 28 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 393, 396 (2015) (describing how international law “fails to account for the unique status of sacred objects”).

- 21Joshua Castellino & Cathal Doyle, An Examination of Concepts Concerning Group Membership in the UNDRIP, in The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: A Commentary 7, 18 (Jessie Hohmann & Marc Weller eds., 2018).

- 22WIPO 2019 Glossary, supra note 1, at Annex 23.

- 23See Castellino & Doyle, supra note 21, at 18.

- 24J. Martinez Cobo (Special Rapporteur of the U.N. Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities), Study on the Problem of Discrimination against Indigenous Populations, ¶ 379, UN Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/1986/Add.4 (1986). This factor acknowledges the colonial period as an important inflection point and recognizes its continuous impacts on indigenous groups. Satisfying this prong presumably requires some historical research into the particularities of when a territory was invaded or colonized, but this research burden seems manageable. A problem with this factor is that it does not leave room to consider the forced displacement brought about by colonialism. See generally Displacement, Elimination and Replacement of Indigenous People: Putting into Perspective Land Ownership and Ancestry in Decolonising Contemporary Zimbabwe (Jairos Kangira et al. eds., 2019). Requiring geographical continuity over time would presumably disqualify any indigenous group that was forced to relocate during or after their territory’s colonization.

- 25Martinez Cobo, supra note 24, ¶ 379.