Subsidiarity and the Best Interests of the Child

In the context of adoption, subsidiarity is the principle that children should remain with their birth families whenever possible, and whenever not possible, that in-country placements should take precedence over intercountry adoption. This Comment looks at the specific meaning of subsidiarity in the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. It highlights that the convention does not require intercountry adoption be a last resort, but rather that “due consideration” be given to placements “within the State of origin.” Then, the Comment looks at the domestic law of India, Colombia, and South Korea, three of the main sending countries in intercountry adoption, as case studies to see how these countries have implemented subsidiarity over time. It reveals a broad trend of these countries implementing stricter and stricter conceptions of subsidiarity over time and concludes that presently all three countries go far beyond what the convention requires, potentially in ways that undermine the best interests of the child.

Introduction

Factual Background

Intercountry adoption (ICA) occurs when a child who habitually resides in one country moves to another for the purposes of an adoption, which creates a permanent parent-child relationship.1 In 1993, the Hague Conference on Private International Law promulgated the Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (HAC).2 The HAC currently binds 105 countries, and is the primary instrument establishing the norms for intercountry adoption under international law.3

One of the most widely debated principles surrounding intercountry adoption is the subsidiarity principle.4 In the adoption context, subsidiarity is the principle that domestic care options for a child should have priority over ICA.5 When it comes to specifics, scholars disagree as to what subsidiarity means both in general and in the context of the HAC. This debate hinges on whether subsidiarity requires all in-country options (including foster care and institutionalization) be prioritized over intercountry adoption, and if not, about which options it holds as preferable to intercountry adoption.6 Scholars have also had extensive debates as to the normative value of different interpretations of subsidiarity.7 This Comment will address the legal debate to get at an understanding of what subsidiarity in the HAC requires before diving into the subsidiarity-related laws and regulations of India, Colombia, and South Korea,8 the top three sending countries9 of intercountry adoptees in 2022.10

Legal Issue and Argument

This Comment is devoted primarily to discussing the development of domestic subsidiarity policy in India, Colombia, and South Korea. It also compares these countries’ application of subsidiarity policy over time to the requirements for subsidiarity in the HAC.

This Comment will analyze whether the general adoption policies of these countries are in line with the HAC. It is worth noting that since the HAC only applies to adoptions where both the sending and receiving country are bound by it,11 the HAC does not require that all domestic adoption policy comply with the convention. This means that even if a general domestic policy does not align with the convention, there is no violation of the convention in a strict sense, so long as the state complies with the convention for adoptions in the convention’s scope. For this reason, this Comment does not seek to allege specific violations of or compliance with the convention. Instead, it seeks to track where countries’ general domestic policies align with the convention, and where they diverge from and go beyond the convention.

An exploration of subsidiarity compliance is timely for several reasons. Firstly, the issue of intercountry adoption made news recently as adoptees from the late 20th century come of age and discover inconsistencies in their adoption histories. These discoveries have prompted several European countries to launch investigations into intercountry adoption practices,12 and even caused the Netherlands to freeze all intercountry adoptions in 2021.13 Furthermore, an ongoing case in the United States involving a U.S. Marine’s adoption of an Afghan child despite the child’s biological family’s desire to raise her brought intercountry adoption into U.S. headlines in late 2022.14 Although this adoption was not within the scope of the convention because Afghanistan is not a party to it,15 if the HAC were to apply, this case would almost certainly raise subsidiarity issues. Secondly, many countries which were formerly top sending countries have stopped processing adoptions after ratifying the HAC in order to restructure their domestic policy in a way that complies with the convention.16 For these countries, a detailed comparison of the ways in which current sending countries handle subsidiarity can be instructive as they evaluate their own options.

Based on the text of the convention and its best practices manual, the subsidiarity principle in the HAC requires only that permanent family solutions in-country be prioritized over intercountry adoption.17 It does not envision intercountry adoption as a last resort or require non-permanent and non-family solutions be prioritized over intercountry adoption.18

At present, India, Colombia, and South Korea all apply a stronger version of subsidiarity than the Hague Convention requires. The Hague Convention does not require a numerical quota on intercountry adoptions, a specific ratio of domestic to international adoptions, or that only certain types of children be placed internationally. Despite this, top sending countries have implemented all these measures at different points in time to advance the end of subsidiarity.19

However, declining adoption numbers,20 and reports of excessive bureaucratic delays in clearing children for adoption21 suggest that subsidiarity as implemented may contribute to fewer children being placed in permanent families. If it is true that an excessively strict implementation of subsidiarity contributes to fewer unparented children finding permanent families, then the stricter conceptions of subsidiarity are likely against the best interests of the child, which is the legal principle underpinning the entire Hague Adoption Convention.22

Overall, the case studies suggest that while in some ways, top sending countries do not fully comply with the text of the HAC, in large part, they presently go far beyond what it requires. Brakman makes a theory-based critique that subsidiarity as it exists in the HAC is not in the best interests of the child.23 This Comment uses an empirical exploration of domestic law and policy in top sending countries to provide qualified support for Brakman’s argument. The Comment concludes that even if the conception of subsidiarity in the HAC is not excessively strict, the way top sending countries implement subsidiarity is in fact more extreme than the convention requires, and that this more extreme version of subsidiarity is likely not in the best interests of the child. It argues that solutions which advance subsidiarity through affirmative encouragement of in-country adoption are more in the best interests of the child than those which artificially or arbitrarily restrict intercountry adoption. The purpose of these arguments is for both the case study countries, other sending countries, and potential sending countries to reconsider bans on intercountry adoption in favor of less strict regimes which honor subsidiarity in a way that does not prevent children from finding permanent family homes. Though what is in the best interest of a given child is a highly fact-specific,24 social science research demonstrates the largely positive developmental effects of placement in a permanent family and the significant developmental setbacks of prolonged institutionalization.25

Any responsible discussion of intercountry adoption must acknowledge the ways in which ICA is connected to colonialism, which in large part has determined which countries “send” and which “receive” children.26 While the scope of this Comment is limited to analyzing the policies of sending countries, it in no way seeks to minimize the historic role27 of receiving countries in illicit adoption practices nor to diminish their responsibility in ensuring the future of ICA better serves the interests of children and birth families than its past.

Roadmap

This Comment will begin in Part II by providing general background on ICA and the HAC. It then will define subsidiarity, and present the debate around what subsidiarity requires, both in general and in the context of the HAC. Part III will look at how the domestic law and policy of India, Colombia, and South Korea with respect to subsidiarity has evolved over time. For each country, this Comment will assess how domestic policy on subsidiarity at various points in time compares to subsidiarity as required in the HAC. It will also look at adoption statistics from the countries to assess whether a given subsidiarity regime is correlated with more in-country adoptions or whether it merely increases the number of children in institutional care. It is important to note, however, that subsidiarity policy is just one of many factors influencing intercountry adoption statistics, and that more research is required in each case to determine a causal relationship between subsidiarity policy and statistical trends. Finally, in Part IV, this Comment will compare the policies of the different countries to illuminate how their approaches have diverged and converged and highlight which approaches appear to be in line with the best interests of the child.

Subsidiarity in Intercountry Adoption

Context of Intercountry Adoption

The modern concept of ICA began in the wake of World War II, and steadily increased in the second half of the twentieth century.28 In the late 1990s and early 2000s, intercountry adoptions increased dramatically.29 However, since 2004, numbers have steadily and dramatically decreased.30 Scholars have cited several reasons for this decline, including changed circumstances in sending countries, reactions to trafficking scandals,31 the rise of surrogacy,32 and pressure in connection with international law.33

As of 2023, many countries which were once top sending countries for ICA have stopped allowing or severely restricted intercountry adoption. Due to a combination of domestic and international pressures, Guatemala, Ethiopia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Vietnam stopped processing new intercountry adoptions, with some of these countries stating they were temporarily pausing in order to come into compliance with international law.34 As of 2023, only Vietnam has resumed and on an extremely limited basis.35 In China,36 increased economic prosperity has led to fewer unparented children and more in-country adoptions.37 Finally, domestic turmoil in Ukraine and Haiti has led to periodic stopping and starting of intercountry adoption from these countries in recent years.38

Scholars debate about the normative value of allowing ICA, and whether international law should encourage or discourage it. Critics of ICA say that it promotes the illegal buying and selling of children.39 They also point out that ICA is often centered around the needs of adoptive parents rather than children,40 and that ICA has historically been a part of colonial and racist practices.41 Finally, opponents argue that ICA is not in the best interests of children as it strips them of their identity.42

On the other hand, proponents of ICA argue that the practice is often in the best interests of the child when permanent family care is not readily available domestically.43 They argue opponents of ICA overemphasize illicit practices in ICA because while there have been horrific cases of abuse,44 there is no persuasive evidence that these are so extensive as to justify banning ICA altogether.45 They argue abuse can be mitigated via domestic and international law.46 Finally, they argue that identity rights, while important, are just one factor to consider in determining a child’s best interests, and that research has shown that identity-related psychological damage to adoptees can be mitigated by better post-adoption practices.47

The Hague Adoption Convention

In the late 1980s, news outlets published stories of kidnapping and child-trafficking in connection with intercountry adoption, which emphasized the need for international organizations to establish more uniform ICA procedures.48 In 1993, the Hague Conference on Private International Law promulgated the Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption whose purpose is “to create standards for intercountry adoption, a system to enforce them, and a forum for communication between the countries involved in an adoption.”49

The HAC’s three main requirements are (1) investigation of the child and parents to ensure the adoption is in the child’s best interests, (2) creation of a central authority in each member state to establish in-country adoption regulations, and (3) cooperation between sending and receiving countries throughout the process.50 As of 2023, the HAC legally binds 105 countries, including the vast majority of sending and receiving countries for ICA.51 Notable exceptions include South Korea, Russia, Ethiopia, and Ukraine, which have all been major sending countries historically.52 Though widespread adoption of the HAC is in some sense a testament to its success, ICA numbers have decreased by 93% since their peak in 2004.53 This may not be cause for celebration however, because the number of unparented children has likely not decreased by this amount, nor have in-country adoptions increased by this amount.54

Subsidiarity and Its Meaning in the Hague Convention

Subsidiarity is best understood as a two-tiered principle.55 Tier one subsidiarity is about keeping a child with her biological family whenever possible.56 Tier two subsidiarity is about giving in-country placements priority over intercountry adoption.57 Tier two subsidiarity comes into play when placement with the biological family is not possible.

Scholars disagree about the precise meaning of tier two subsidiarity, specifically about which types of domestic placements should be prioritized over ICA.58 This debate is exacerbated by the fact that the two main international law instruments outlining the principle, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the HAC refer to subsidiarity with meaningfully different language. The text of the CRC suggests that subsidiarity requires ICA be considered only as a last resort. It says that states “shall . . . [r]ecognize that inter-country adoption may be considered as an alternative means of child’s care, if the child cannot be placed in a foster or an adoptive family or cannot in any suitable manner be cared for in the child’s country of origin.”59 The text of the HAC is more open to ICA and implies that a permanent ICA placement is preferable to in-country placements in foster care and institutions. For example, the preamble of the HAC states that “intercountry adoption may offer the advantage of a permanent family to a child for whom a suitable family cannot be found in his or her State of origin.”60 The language in the preamble emphasizing permanent family solutions implies that any in-country placement which does not offer a permanent family would not, in most cases, be preferable to ICA.

The main section on subsidiarity in the HAC states that:

An adoption within the scope of this convention shall take place only if competent authorities of the State of origin . . . have determined, after possibilities for placement of the child within the State of origin have been given due consideration, that an intercountry adoption is in the child’s best interests.61

This text contains at least three separate requirements. First, that subsidiarity refers to placements within the state of origin, which is different than placements with citizens of the state of origin or placements in families of the child’s birth culture. The case studies on India and Colombia discussed later illustrate how these can be meaningful differences. Second, the HAC requires due consideration of in-country options. It is not clear what due consideration requires precisely, and since the HAC is a private international law instrument, there is no caselaw on the issue.62 A common sense reading of due consideration seems to require at a minimum some consideration of in-country placements but does not require automatic priority for in-country placements. Finally, the mention of the child’s best interests refers to the widely accepted principle of the best interests of the child, first outlined in the CRC.63 Ensuring that intercountry adoptions take place in the “best interests of the child” is also mentioned as an overall objective of the HAC. Despite referring to subsidiarity differently than the CRC, the HAC incorporates the best interests of the child principle, “taking into account the principles set forth in international instruments in particular the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.”64 This may mean that the HAC is meant to take the same stance on subsidiarity as the CRC, or it could mean that the HAC has taken the CRC into account and deliberately chosen to diverge.

The text of the HAC (analyzed above), combined with evidence from its legislative history and its best practices manual suggest that the HAC’s version of subsidiarity is an intentional divergence from the version in the CRC. In addition to the text, scholar Chad Turner argues that the drafting history of the HAC, combined with the family-oriented language in the HAC text suggest that subsidiarity in the context of the HAC does not require that nonfamilial and nonpermanent in-country placements be considered before ICA.65 As evidence, he highlights how the original version of the HAC preamble read “intercountry adoption may offer the advantage of a permanent family to a child who cannot in any suitable manner be cared for in his or her country of origin.” 66 Turner then points out that the convention drafters changed this to “a child for whom a suitable family cannot be found.” 67 The key difference here is that the earlier draft statement suggests that any form of care in-country is preferable to ICA, whereas the statement actually adopted focuses only on family placements as preferable to ICA. These changes came about after extensive lobbying by representatives of Colombia and Bolivia who believed this language best protected the fundamental right of a child to a family.68

The drafters also rejected competing proposals made by Poland and Egypt to alter this language to explicitly state that non-permanent forms of in-country care should be preferable to ICA.69 Brakman points out that the Hague Conference on Private International Law’s70 Guide to Good Practice also supports this position.71 It states that putting ICA as “a last resort” is “not the aim of the Convention” and that “in the majority of cases” institutionalization is “a last resort.”72 Based on this evidence, it seems Brakman is correct in her assertion that while the normative value of subsidiarity in the HAC can be debated, it is clear the Convention does not require all in-country care options be exhausted before looking to ICA.73

From a normative standpoint, Brakman argues that subsidiarity, even the relatively lenient version in the Hague Convention, is not in the best interests of the child.74 Proponents of subsidiarity justify it for three reasons: 1) limiting international placements incentivizes development of in-country adoption infrastructure,75 2) ICA undermines state sovereignty and has historically been a part of racist and colonial practices,76 and 3) subsidiarity preserves a child’s heritage rights.77

In response, Brakman argues that the first two reasons, laudable and valid as they may be, have no bearing on the best interests of the child, a key principle in the HAC and CRC, both of ICA’s governing international law instruments.78 She further argues that the psychological damage suffered by some intercountry adoptees is not inherent to ICA, and could be mitigated by better post-adoption practice.79 She concludes by arguing that even to the extent heritage rights are relevant to determining the best interests of the child, they are only one of many factors in this determination and should be treated as such.80

In summary, Part II of this Comment establishes that subsidiarity in the HAC has three requirements: that countries 1) give due consideration to placements 2) within the state of origin, and that ICA placements are 3) in the child’s best interests. While scholars disagree on the normative value of subsidiarity, the text of the HAC, its legislative history, and its good practice manual strongly suggest that the HAC does not require ICA be considered only as a last resort.

Case Studies

Part III of this Comment will analyze how India, Colombia, and South Korea have implemented subsidiarity domestically over time. Exploring how top sending countries implement subsidiarity provides an empirical basis to evaluate the legal and normative arguments on both sides of the debate on subsidiarity.

India

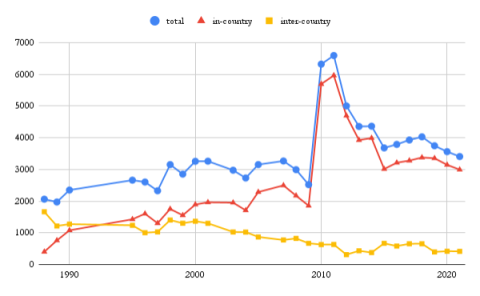

To introduce trends in Indian adoption over time, Figure 1 compiles statistics from several sources to illustrate how in-country and intercountry adoption have evolved over roughly a thirty-year period. It reveals a gradual decline in intercountry adoptions, coupled with a notable increase in in-country adoptions.

Figure 1: Indian Adoption Placements, 1989-2022

Notes: The figure reports Indian adoptions from 1989–2022. It breaks out the results separately for in-country adoptions, intercountry-adoptions, and total adoptions. The statistics are compiled from several sources.81

Initial policies: 1986–2002.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, ICA was governed by the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890 (for non-Hindus) and the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956 (for Hindus).82 At this time, adoption was more challenging for non-Hindus, because they were only able to adopt by first obtaining a legal guardianship.83 The Juvenile Justice Act of 2000 and Juvenile Justice Amendment Act of 2006 laid out a new process for adoption governed by a central authority, but this framework made no reference to subsidiarity or intercountry adoptions.84

The 1986 Supreme Court case Pandey v. Union of India lays out India’s pre-convention guidelines for ICA.85 With respect to subsidiarity, Pandey indicates a preference for in-country placement, but emphasizes that expeditious placement with a loving family is most important.86 Pandey is also critical of procedural delays in adoption, and allows agencies to offer children “simultaneously” to Indian and foreign parents to decrease processing times.87 Pandey also takes several steps to make ICA easier, such as removing a requirement in Delhi that domestic agencies have joint guardianship in intercountry adoptions,88 and requiring procedural changes to shorten the timeline of intercountry adoptions.89

Subsequent pre-HAC jurisprudence and policy continued to acknowledge the value of subsidiarity, but only as a concern secondary to placing the child in a loving family.90 In 1992, the Indian Supreme Court acknowledged that the rationale behind finding Indian parents or parents of Indian origin is “to ensure that as far as possible Indian children should grow up in Indian surroundings so that they retain their culture and heritage.” 91 At the same time, the Court declined to reconsider a lower court decision which disallowed the state government’s attempt to block an adoption when it had not yet offered the child to Indian parents92 because it found that drawing out this case was not in the best interest of the child.93 This approach was not unique to the courts given that fact that, in 1990, the national government established the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA). CARA is an autonomous body operating under the Ministry of Women & Child Development whose original mandate was “to find a loving and caring family for every orphan/destitute/surrendered child in the country.”94 This family-focused language echoes the sentiment in Pandey and subsequent caselaw which emphasizes the importance of placing children in permanent families.

India’s pre-HAC subsidiarity policies are probably not sufficient to meet the standards of subsidiarity laid out in the HAC, though they are likely in line with the spirit of the convention. Pandey allows simultaneous referral of children to foreign and Indian families,95 which probably doesn’t guarantee “due consideration” for in-country placements as required by the convention.96 However, the general ethos in Pandey, subsequent decisions, and CARA’s initial mandate are in line with the spirit of the convention. CARA’s initial mandate was to “find a loving and caring family for every . . . child in the country.”97 Pandey, and subsequent caselaw98 acknowledge that while in-country placements are better when available, prioritizing expeditious placement in a loving family should be the priority in adoption decisions.99 This framework is largely in line with the spirit of the HAC in that it centers the best interests of the child and recognizes ICA can offer “the advantage of a permanent family” when one is not readily available domestically.100

Adoption statistics from 1988–2001 are consistent with the hypothesis that the subsidiarity framework in Pandey played a role in increasing Indian in-country adoptions without resulting in significantly fewer total adoptions. Specifically, from 1988 to 1990, a few years after Pandey was decided, intercountry adoptions decreased dramatically while total adoptions remained consistent.101 Then, from 1995–2001, the percentage of intercountry adoptions continued a downward trajectory while the number of total adoptions continued to increase.102 Though more research is needed to infer a causal relationship between Pandey and these numbers, if it is true that such a link exists, the Pandey framework can be considered a highly successful subsidiarity framework in that it raised in-country placements and lowered international placements without resulting in fewer total adoptions. Increased total adoptions is a positive in the Indian context, where the number of children in institutional care far outnumbers the number placed in adoptive families,103 especially given the international community’s consensus that family-based care is preferable to institutionalization.104

Stricter policies: 2003–2014.

India ratified the HAC on June 6, 2003.105 India’s legal system reflects a dualist approach to international law, which means that international law does not become binding until domestic legislation is enacted to give it effect.106 India made its first changes to its domestic adoption policy via CARA’s 2006 adoption guidelines. With respect to subsidiarity, the 2006 regulations institute a waiting period during which the relevant domestic agencies must look for an in-country placement before offering children for ICA. For children with disabilities, the waiting period was ten days, for children over six years of age or with siblings, it was fifteen days, and for all other children it was thirty days.107 Under this framework, only adoptions by Indian citizens residing in India were considered during the initial period.108 Adoptions by Indian citizens living abroad and adoption by non-citizens of Indian descent living abroad were prioritized over adoptions by non-Indians, but all of the above were considered ICA.109 CARA subsequently updated its policies in 2011, removing the 30/10 day in-country referral requirement, but listing that preference for in-country placements as a “fundamental principal governing adoption” and adding a requirement that 80% of adoption placements be with Indian parents residing in India.110 The 2011 guidelines also lay out an order of preference for different care options for children as follows: 1) biological family, 2) in-country adoption, 3) ICA, 4) other non-institutional (foster) care, and 5) institutional care.111 All of CARA’s subsequent guidelines and regulations have preserved this hierarchy.112

In the first decade after the ratification of the HAC, 2003–2014, India introduced an increasingly strict conception of subsidiarity that went far beyond what the HAC requires, arguably at the expense of the best interests of the child. The modest waiting periods before considering ICA that CARA outlined in the 2006 guidelines are probably enough to bring the Pandey framework into compliance with the HAC’s “due consideration” requirement.113 In this framework, children can only be referred to Indian citizen families residing in India during the waiting period, which is also aligned with the idea that “due consideration” must be given to “placement of the child within the State of origin.”114 The 2011 guidelines, in effect until 2015, instituted an even stricter conception of subsidiarity, which replaced waiting periods with a requirement that 80% of children placed in adoption be placed with Indian citizen families residing in India.115 An anonymous CARA employee told the Indian press in 2014 that the agency intentionally kept the pool of non-resident adoptive parents small because “due to the existing rules we don’t have many children to list for adoption.”116

In the years following the 2006 guidelines, total adoption numbers continued to increase as the percentage of intercountry adoptions continued to decrease. This trend suggests that the implementation of the modest waiting periods was positive in that they permitted India to comply with the convention and did not disrupt the positive trends of increased in-country adoptions and increased total adoptions. In the years prior to the implementation of the 80:20 ratio, the percentage of intercountry adoptions was already quite low: it had not been above thirty percent in over five years.117 In the years during which the 2011 guidelines were in force, 2011–2015, intercountry adoptions made up around eight percent of total adoptions, and the total adoption numbers for India declined each year, suggesting the strictness of the guidelines is a plausible reason for the decrease in both in-country and intercountry adoptions.118 This is further supported by the fact that in the years after the 2011 guidelines were repealed, the ICA percentage rose to around sixteen percent, and total adoption numbers also modestly increased for a few years, despite a decline in global intercountry adoptions.119

Slight walk-back of strictest policies: 2015–2023.

India’s statutory framework governing adoption did not address subsidiarity explicitly until 2015.120 The Juvenile Justice Amendment Act of 2015 defines ICA and lays out rules relevant to subsidiarity. The Act defines ICA as “adoption of a child from India by non-resident Indian or by a person of Indian origin or by a foreigner.”121 Once a child is certified as adoptable, the act mandates that both specialized adoption agencies122 and state adoption agencies conduct a sixty-day search for domestic adoptive families, after which point the child can be offered to approved families for ICA.123 The Act also requires that children with disabilities, siblings, and children above the age of five receive priority over other children in ICA, and that prospective parents of Indian descent have priority over prospective parents of non-Indian descent.124

The Juvenile Justice Amendment Act of 2015 also delegates further regulation of adoption to CARA.125 This explains why CARA’s 2006, 2011, and 2015 publications were labeled as guidelines while CARA publications post-2015 are labeled as regulations. Since the Juvenile Justice Amendment Act of 2015, CARA has published two sets of adoption regulations, one in 2017 and one in 2022. With respect to subsidiarity, the 2015 guidelines did away with the 80:20 ratio from the 2011 guidelines, and re-instated waiting periods. This time, the waiting periods were fifteen days for children with disabilities, thirty days for children with siblings or over the age of five, and sixty days for all other children.126 The 2017 regulations did not implement any changes from the 2015 guidelines with respect to subsidiarity.127 CARA’s most recent set of adoption regulations, released in 2022, allows OCI (Overseas Citizen of India) Cardholders128 to adopt during the waiting period in addition to resident Indians and non-resident Indians. It also states that all three of these groups have equal priority for adoption.129 The 2022 regulations also make a slight change to the waiting periods from the previous regulations, in that during the initial 60/30/15 day waiting period, children are referred to families in order of seniority (counted by when the prospective parents submit all required documents).130 Then, after the initial period has expired, there is another seven-day period during which agencies may offer children to resident / NRI (non-resident Indians) / OCI families irrespective of seniority.131 After this period of seven days, the agencies must offer children to foreign families for fifteen days.132 At this point, if the agencies have not placed a child, they designate that child as “hard to place” and may consider foster care placements in addition to adoption.133

Since 2015, India has attempted to walk back its strict conception of subsidiarity in ways that, while not in line with the plain text of the HAC, are still in line with its spirit. The sixty-day waiting period in the Juvenile Justice Act is likely long enough to ensure “due consideration” of in-country placement.134 The lesser waiting periods in the CARA regulations for older children, siblings, and children with disabilities are also probably sufficient, and arguably do not violate the Juvenile Justice Act because that act specifies that these categories of children should be prioritized for intercountry adoption.135 Although adoptions by NRIs and OCI cardholders are excluded in the definition of in-country adoptions,136 India began allowing referrals to NRI parents during the period from 2015 onwards, and added OCI Cardholders to this group from 2022 onwards.137 The 2022 guidelines explicitly state that “[n]on-resident Indian and Overseas Citizen of India Cardholder prospective adoptive parents shall be treated at par with Indians living in India in terms of priority for adoption.”138 These changes are in tension with the text of the HAC, which requires due consideration of “placement of the child within the State of origin.”139 Given that NRIs and most OCI cardholders reside outside India, allowing these individuals to adopt during the waiting period violates the plain text of the HAC. Treating NRIs and OCI cardholders “at par” with resident Indians as a broader policy is also probably a violation of the convention. At the same time, the justification behind subsidiarity is that it maintains continuity of the child’s culture, language, and nationality.140 According to an interpretation of the plain text of the convention, in-country placements should probably not be “at par”141 with NRI and OCI placements abroad. That said, putting Indian children with families of Indian descent and culture abroad is less disruptive to identity related rights than placement in a non-Indian family. If giving these groups equal priority results in more children being placed in permanent families with a similar cultural background, these changes are still in line with the spirit of the convention, given its emphasis on the best interests of the child.

As mentioned above, during the first few years after abandoning the 80:20 ratio, India’s total number of adoptions modestly increased, and its percentage of intercountry adoptions climbed from the single digits to hover around fifteen percent.142 In the years since 2019, both total adoptions and the percentage of intercountry adoptions has gone back down to ten to twelve percent,143 though the extent to which the pandemic temporarily depressed the rate of ICA remains to be seen. Some have speculated that the recent decline in Indian adoptions is in part due to the rise of surrogacy as an alternative to adoption.144

Although India has walked back its strictest interpretations of subsidiarity, its present application of the concept in some ways violates the convention and in other ways goes beyond what it requires. Given the number of orphans in India, and the relatively low numbers of both in-country and intercountry adoptions, some have criticized the current regime as not being in the best interests of children.145 The problem is further exacerbated by the fact that the process is plagued with excessive bureaucratic delays.146

The recent case PKH v. Central Adoption Authority demonstrates how courts, exasperated with the current framework, have thought of creative and concerning workarounds to official procedures. In PKH, the Delhi High Court decries India’s “abysmal rate of adoption” and upholds a “direct” adoption of an Indian child by a Canadian citizen couple of Indian heritage who had distant ties to the child’s biological family.147 Although the family in question had been cleared for adoption by Canada according to HAC processes, the family attempted to adopt the child directly from her biological mother via judicial certification, and notably without certification from CARA.148 When the family was asked by Canada to seek approval from CARA, CARA refused, alleging direct adoptions violated the Juvenile Justice Act and the Hague Convention.149 Upon hearing this case, the Delhi High Court held that direct adoptions did not have to go through CARA as they were not within the scope of the law that applied at the time the child was born, and that failing to go through CARA did not violate the Hague Convention given that a judge had certified the adoption.150 Regardless of whether there were any illicit practices involved in this case, the way in which the Delhi High Court circumvented CARA suggests that the strictness of the current regime may have the unintended result of eroding the protective role of the Central Authority, one of the safeguards the HAC attempts to put in place.151 Given that India’s current subsidiarity policies go beyond what the convention requires, perhaps a loosening of these policies with a mind to decreasing procedural delays could serve the dual purpose of facilitating in-country and intercountry adoptions and avoiding the need for future workarounds like the one in the PKH case. Given the efficacy of the Pandey framework in promoting in-country adoption without decreasing total adoptions, perhaps this framework, with slight modifications to meet the requirements of the convention, could be a substitute for the present strict regulations and a feasible way forward for India.

Colombia

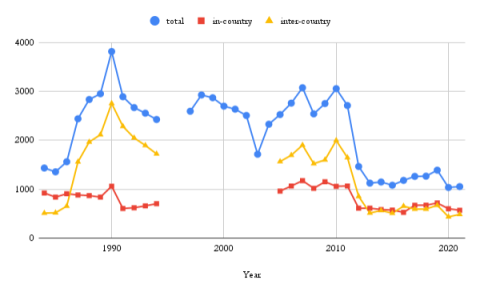

To introduce trends in Colombian adoption, Figure 2 compiles statistics from several sources to illustrate how in-country and intercountry adoption have evolved over roughly a thirty-year period. It reveals an initial increase, followed by a leveling out and gradual decline, coupled with a notable decrease in intercountry adoptions.

Figure 2: Colombian Adoption Placements, 1984–2022

Notes: The figure reports Colombian adoptions from 1984–2022. It breaks out the results separately for in-country adoptions, intercountry adoptions, and total adoptions. The statistics are compiled from several sources. Gaps in the table are due to lack of available statistics.152

Initial policies: 1989–1997.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, adoption policy in Colombia shifted from a private contract to a state-managed system. Colombia first provided explicitly for adoption in Law 140 of 1960.153 This law allowed adoption by a single parent of the same sex as the child or by married couples and required a notarized license to adopt signed by the adoptive parent and the adoptee or the individual with custody over the adoptee.154 Law 75 of 1968 then created the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, the “ICBF”), whose mandate was to “ensure that minors who are not under parental authority or control are under the immediate care of the people or institutions best suited for this, taking into account the age and other conditions of the minor.”155 Then, Law 5 of 1975 moved adoption more completely into the public domain, establishing that all adoption programs in Colombia had to be through the ICBF or an agency authorized by the ICBF.156 The first mention of subsidiarity in Colombia’s statutory framework was in the 1989 Children’s Code, which stated that adoption requests from eligible Colombians would be preferred to requests from eligible foreigners.157

Colombia’s subsidiarity policy from the 1989 Children’s Code is, for the most part, textually compliant with the HAC’s subsidiarity requirements. The 1989 Children’s Code was Colombia’s acting policy on subsidiarity from 1989–2006, which includes significant time periods both before and after Colombia ratified the HAC in 1998.158 The code states simply that authorized entities “shall prefer, insofar as they comply with the requirements established in this code, applications presented by Colombians to those presented by foreign adopters.”159 The code is not explicit about whether “Colombians” is inclusive of Colombian nationals residing outside Colombia, but it is logical to assume that “Colombians” would include all Colombian citizens unless otherwise specified. If this is the case, this policy has the same issue as the present Indian policy in that it does not fit with the letter of the HAC, though it does comply with its spirit. Other than this, the text of Colombia’s policy, though vague, likely permits due consideration of placement options in-country.

Moderate policies: 1998–2012.

The HAC into force in Colombia on November 1st, 1998.160 However, Colombia’s statutory subsidiarity framework remained unchanged from 1989 until 2006. Law 1098 of 2006 lays out the present framework for intercountry adoptions from Colombia.161 The law establishes the ICBF as the central adoption authority in Colombia.162 It outlines Colombia’s commitment to subsidiarity in Article 71, saying the ICBF shall “en igualdad de condiciones” (all else equal), prefer Colombian families residing within Colombia or outside Colombia to foreign families.163 The law also gives preference to foreign families residing in countries bound by the HAC over foreign families residing in countries not bound by the HAC. 164

Although intercountry adoption was not explicitly a part of Colombia’s statutory framework until 1989,165 the country has engaged in ICA since at least the 1960s. In 1969, Colombia was already placing a small number of children with foreign families.166 By 1984, 511 Colombian children had been placed abroad, which made up thirty-five percent of total adoption placements that year.167 Intercountry adoptions continued to increase in the early 1990s, with intercountry placements making up seventy-four percent of placements from 1989–1994.168 From 1987 until 2012, the total number of adoptions remained relatively stable at around 2,000–3,000 per year.169 By the early 2000s however, the percentage of international placements had modestly decreased: sixty-one percent of total placements were international from 2005–2012.170

Both statistics and investigative reports into ICBF practices during the period from 1989 to 2006 call into question the level of consideration the ICBF gave to in-country placement, though practices improved slightly after Colombia joined the HAC. Hoelgaard points out that the ICBF made contacts with Western adoption experts and agencies and contracted with specialized private agencies within Colombia to facilitate placement of children abroad.171 She interprets this, combined with the increase in intercountry adoptions that continued through at least the mid-1990s to imply that the ICBF was actively pursuing foreign placements. The fact that by the early 2000s intercountry adoptions increased while total adoptions remained constant suggests a possibility that after signing the Hague Convention, Colombia changed the manner of its policy implementation to provide more consideration to in-country placements. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that Colombia’s modest decrease in ICA occurred during a period when total intercountry adoptions reached their all-time high.172 At the same time, more research into ICBF practices is required to determine causality, as this trend is also consistent with the rise of other major sending countries in the region, such as Guatemala.173

Strict policies: 2013–2023.

Colombia next modified its subsidiarity policy in 2013 in response to public outrage at allegations that the ICBF was engaged in illicit practices. In 2012, the investigative Journalism program Séptimo Día aired a piece entitled “The Other Side of Adoption,” which accused the ICBF of rampant corruption, including allegations that it accepted inordinate sums to process international adoptions and declared children as adoptable before the law allowed.174 After the backlash resulting from this program, the ICBF modified its adoption policy in a way that strengthened both Tier 1 and Tier 2 subsidiarity.175 The new changes implemented additional measures to place the child with biological relatives, requiring that social workers must carry out searches for natural family and relatives all over the country.176 Although these searches are supposed to be capped at six months, they often take years, and during this time the child is typically in institutional care.177 Another 2013 change was that foreign nationals could no longer adopt from the general pool of adoptees, but rather only apply to adopt children with “special characteristics and needs” which includes children with special needs, children above seven, and groups of siblings.178 This restriction does not apply to Colombian citizens living outside Colombia.179 In 2016, the category of children with special characteristics and needs was narrowed to children above ten, rather than above seven, further limiting the pool of Colombian children eligible to be adopted internationally.180

ICA numbers in Colombia do not appear to go up and down with subsidiarity policy prior to 2012, upon which both adoptions and intercountry adoptions decreased significantly. After the outcry in 2012 and institution of new policies in 2013, both total adoption and the percentage of intercountry placements decreased. Forty-seven percent of total placements have been international since 2012, and total adoption numbers have hovered around 1,000–1,200 adoptions per year.181

The 2013 reforms to Colombia’s subsidiarity policy strengthened the country’s commitment to subsidiarity in a way that goes far beyond the requirements of the HAC, and these changes have coincided with a significant drop in intercountry adoptions, as well as total adoptions. In terms of Tier 1 subsidiarity the HAC requires that the consent of the birth mother, where required, is given freely, without compensation, and after the birth of the child.182 There is no specific requirement in the convention to conduct searches for the biological families of children whose families cannot be located. Conducting some level of a search in these cases is likely in the child’s best interest, in case the child was separated from her natural family without the family’s consent. However, Piché conducted interviews with actors in Colombia’s adoption processes who stated that these searches often take months and sometimes years, during which time the child is in institutional care.183 It is unclear how often these searches result in the return of the child to a biological relative. Prolonging searches for natural relatives beyond a certain point may not be in the child’s best interests when there are permanent families both in Colombia and abroad willing to adopt these children.184 The problem is further exacerbated by the fact that the legal professionals who are mandated to evaluate new arrivals to institutions often do not do so, or do so only partially, resulting in the child in question never becoming adoptable.185 The actors interviewed by Piché speculate that some institutions fail to process new arrivals or process them slowly in order to maintain their numbers high enough to qualify for ICBF subsidies.186 According to 2019 statistics by the Colombian organization Casa de La Madre y El Niño, Colombia had over 25,000 children living in institutions, only 6,300 of whom were eligible for adoption.187

The 2013 changes to Tier 2 subsidiarity, which only allow for older children, siblings, and children with disabilities to be placed in ICA also go beyond the convention’s due consideration requirement. The logic behind this policy is that these types of children are hard to place and care for domestically,188 which in some sense echoes the school of thought that ICA should be a last resort. One might think that not allowing the youngest and healthiest adoptable children to go to ICA placements would increase the number of these children who find adoptive families domestically. Unfortunately, statistics suggest that this policy does not coincide with an increase in in-country adoptions. In fact, coincides with a decrease in international ones. Colombia’s decrease in ICA began in 2011 and leveled out around 2013. The fact that the decline seems to have begun before the 2013 regulations suggests that this is a case where practice may have changed before the law did, but it does not negate the possibility that the two events are related.

In the past thirty years, Colombia has employed a progressively strict conception of subsidiarity, which now goes far beyond the requirements of the HAC. Colombia’s present adoption system is plagued by systemic issues and bureaucratic delays, and the country’s current Tier 1 and Tier 2 subsidiarity policies may be a contributing factor in that present reality. Bautista Lopez argues that although there are new legal protections in place to regulate adoption, evidence suggests corrupt and elicit adoption practices are common in Colombia.189 If she is correct, it is possible that current policies have both decreased adoption rates and failed to mitigate illicit practices. As of 2020, the ICBF stated it is aware of the bureaucratic hurdles preventing adoption and is working to solve them.190

South Korea

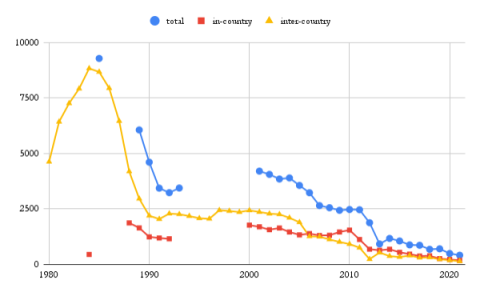

To introduce trends in South Korean adoption, Figure 3 compiles statistics from several sources to illustrate how in-country and intercountry adoption have evolved over roughly a forty-year period. It reveals a gradual decline in total adoptions, coupled with a moderate increase in the ratio of in-country to intercountry adoptions.

Figure 3: South Korean Adoption Placements, 1984–2022

Notes: The figure reports South Korean adoptions from 1980–2022. It breaks out the results separately for in-country adoptions, intercountry adoptions, and total adoptions. The statistics are compiled from several sources. Gaps in the table are due to lack of available statistics.191

Although South Korea signed the HAC in 2011, it has yet to ratify it and is therefore not legally bound.192 South Korea is the only current top sending country in this position.193 South Korea is also unique among the three case study countries in its economic prosperity.194 Despite the fact that South Korea is not bound by the HAC, using it as a case study can still be illustrative as a way to understand whether non-convention members’ subsidiarity trends match those of convention members. It could also be useful to examine solutions to subsidiarity issues that can be pursued outside the framework of the convention, which only applies when both countries processing the adoption are bound.195

Historical context: 1953–1975.

South Korea began intercountry adoptions in 1953 after the Korean War.196 The first generation of Korean intercountry adoptees were mostly mixed-race with Korean birth mothers and foreign military birth-fathers.197 Since many of these children lived with their birth mothers and were actively recruited for ICA by joint U.S. and South Korean efforts, some have called this initial wave a forced displacement of mixed-race children.198 Although by the 1970s, most intercountry adoptees were no longer directly connected to the war,199 intercountry adoptions continued due to the ICA infrastructure which South Korea and the U.S. set up as a result of the war.200 For the rest of the twentieth century, South Korea led the world in international adoptions, and it is still a top sending country,201 though numbers have majorly decreased.202 One scholar, Sook K. Kim points to the legacy of the war, strong cultural taboos,203 and income inequality204 to explain the current prominence of ICA in South Korea despite the country’s present economic prosperity.

Initial policies: 1976–2006.

In 1976, after decades of criticism from North Korea for “selling” Korean children to the west, 205 South Korea put its first subsidiarity policy in place under the 1976 Special Adoption Law and “Five Year Plan For Adoption and Foster Care.”206 The plan set the goal of reducing intercountry adoptions by 1,000 per year and increasing in-country adoptions by 500 per year through a quota system where the previous year’s numbers determined the next year’s quota.207 The plan also set out the goal of phasing out intercountry adoption completely for all except those considered hard to place by the government: mixed-race children and children with disabilities.208 However, a few years later president Chun Doo Hwan reversed this policy because he viewed ICA “as part of emigration expansion and a ‘good-will ambassador policy.’”209

Leading up to the 1989 Seoul Olympics, media outlets published “humiliating” reports on South Korea’s adoption industry, which subjected the country to negative attention on a global stage and prompted yet another plan to phase out ICA, this time by 1996.210 The post-Olympic plan also included tax reductions for Korean families who adopted domestically.211 The next administration, perhaps seeing the 1996 deadline as overambitious, took a longer term strategy: it aimed to decrease ICA by three to five percent each year, and fully phase it out by 2015.212

The subsidiarity policies which South Korean officials espoused prior to 2007 likely complied with the standards of the HAC on paper. The 1976 “Five Year Plan,” and the government’s various commitments throughout the 1990s to gradually phase out ICA through yearly quotas were more focused on decreasing ICA than they were on giving in-country options due consideration. When describing these initial efforts to prioritize subsidiarity, scholar Katherine Moon argues that “embarrassment and loss of national pride were the drivers [of these policies], not the best interests of the child.”213 While it may appear that this early South Korean policy complied with the standards of the HAC on paper, these policies in fact complied neither with the text nor the spirit of the convention. This is because they were more focused around categorical decrease of ICA rather than considering in-country placements and the best interests of the child.

South Korea’s initial subsidiarity policies do not coincide with changes in adoption statistics. Both total adoptions and intercountry adoptions from Korea peaked in 1985, which had 9,287 total adoptions, ninety-five percent of which were intercountry adoptions.214 After this, adoptions declined dramatically until 1991, which had 3,438 total adoptions, sixty-four percent of which were intercountry adoptions.215 The fact that this initial decrease was linear whereas subsidiarity policy in these years was varied suggests this decrease corresponds more with the country’s bad press in the late 1980s than it does to any specific policy initiative. After this five-year period of decrease, from 1992–2006, total adoptions hovered between 3,200 and 4,200 per year, with the percentage of intercountry adoptions remaining relatively stable.216

Stricter policies: 2007–2023.

The next major changes to subsidiarity policy came into effect around 2007. The government adopted several policies to promote in-country adoption, such as offering monthly financial support to in-country adoptive parents,217 permitting single-parent adoption, relaxing age limits for in-country adoption, and designating May 11th as National Adoption Day.218 To decrease intercountry adoptions, the government instituted a five-month waiting period and a quota system which required intercountry adoptions decrease by ten percent each year.219 It also tightened marriage and age requirements for foreign adoptive parents.220

In 2011, South Korea passed its most recent adoption legislation, the Act on Special Cases Concerning Adoption (the “Special Adoption Act” or the “Act”).221 The Act had two primary purposes, both connected to subsidiarity: to keep children with their birth families, and also to reduce the number of foreign adoptions and prioritize in-country adoptions in situations where remaining with the birth family is not possible.222 To this joint end, the Act institutes additional registration requirements for birth parents, requires local and national governments to implement measures to find more in-country adoptive families, and gives adopted children the same legal relationship to their adoptive parents as biological children.223 The Act requires the national and local government hold campaigns and events to promote in-country adoption each year during National Adoption Day and the following week.224 In a notable departure from previous policies, the Special Adoption Act does not contain any quotas or numerical limits on ICA, and instead requires governments to place “the foremost priority on finding adoptive parents in Korea first.”225

The 2007 changes to adoption policy brought South Korea up to and likely beyond the standards of the HAC with respect to subsidiarity. Instituting a five-month waiting period before intercountry adoption is certainly enough time to give due consideration to options within the country. Combined with this, the concrete affirmative measures to promote in-country adoption, rather than just decrease ICA as previous policies had done, is more in line with the best interests of the child. There are some elements of the 2007 policy which go beyond what the HAC requires. For example, the waiting period is more than enough time to give due consideration to in-country options, and the affirmative measures to promote in-country adoption ensure this will happen, so instituting a requirement of a ten percent decrease in ICA on top of that likely prevented some children from finding loving homes. For example, an adoption agency employee spoke in 2011 about how boys and children with disabilities were especially hard to place within Korea and said that each year fewer and fewer of them were able to be placed with families because international quotas were already met.226 That being said, the statistics from the years following 2007 suggest that overall, the policies at the very least coincided with a positive trend: the number of adopted children remained fairly constant, even as ICA numbers decreased, meaning more domestic placements.227

The 2011 Special Adoption Act added additional restrictions to those in the 2007 policy,228 going far beyond what the HAC requires and possibly playing a role in a decrease in both intercountry and in-country adoption in Korea. The legislative intent behind the Act, which was supported by groups of adult Korean Adoptees, was to keep children with their biological families and increase in-country adoption.229 This intent is almost exactly in line with subsidiarity as laid out in the HAC. In practice however, the act may have failed to achieve these objectives. After the act passed, there was an increase in abandoned babies in “baby boxes” in Korea, though there is disagreement about whether this was a direct result of the act, or a result of misconceptions of what the act requires of birth mothers and widespread media coverage of “baby boxes.”230 Though 2011 was the last major change to South Korea’s subsidiarity policy, there was a minor change in 2014, which relaxed age requirements for non-South Korean citizens of Korean descent.231 The years following 2011, in addition to having more abandoned babies in baby boxes, also had fewer adoptions, both domestically and internationally.232 That being said, the decrease in adoptions, though possibly in-part a result of the act, also likely has other causes. The decrease in Korea could also be connected to the decriminalization of abortion in 2019,233 the country’s rapidly decreasing birth-rate,234 and the larger general trend of decreasing adoptions globally since the mid 2000s.235

Both the 2007 and 2011 policy changes coincide with decreases in both ICA and total adoption. In the years from 2007–2011, intercountry adoptions decreased each year, presumably because of the quota system, but total adoptions remained constant at around 2,400 per year, because in-country adoptions were increasing during this period.236 In 2012, total adoptions fell to 1,880 and have been on a downward trend ever since, with only 324 adoptions (182 intercountry and 142 in-country) recorded in 2022.237 It is notable that in the years since 2012, both intercountry adoptions and in-country adoptions have decreased, and the percentage of intercountry adoptions each year has hovered around forty percent.238 This suggests that the decrease in intercountry adoptions in this period likely did not cause an increase domestic adoptions.

In summary, the extremely high number of international adoptions from Korea in the late twentieth century certainly warranted a significant policy change. After many failed attempts, South Korea has gotten its in-country to intercountry adoption ratio in check through a combination of affirmatively encouraging in-country adoption and restricting ICA. However, it is worth investigating whether current adoption policies are contributing to the striking decrease in both in-country and intercountry adoption from South Korea, especially given evidence that the number of abandoned children may be increasing.

Comparison Between Countries

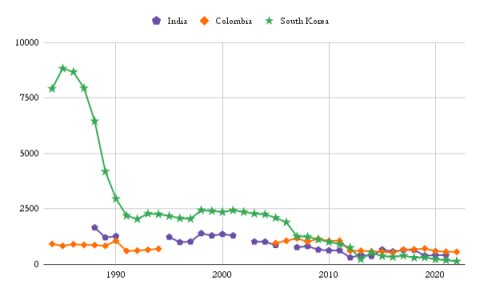

To compare the case study countries’ adoption trends, Figure 4 compiles statistics from several sources to illustrate how many intercountry adoptions the countries have had over time relative to one another. It reveals the massive scale of ICA from South Korea in the 1980s,239 with the numbers of all three countries declining and converging over the past ten years.

Figure 4: Intercountry Adoptions by Country 1980–2022

Notes: The figure reports intercountry adoptions from the case-study countries from 1980–2022. The statistics are compiled from several sources. Gaps in the table are due to lack of available statistics.240

To highlight the many ways in which the case study countries’ approaches to subsidiarity converge, and the few significant ways they diverge, this Part explicitly compares the countries to each other. It begins by comparing the similar way in which policies have developed over time. This part then addresses what appears to have spurred their development, and finally looks at significant differences among the countries in their present policy.

Comparison of Policies over Time

Looking how each country’s policies have evolved over time, roughly countries have gone through three steps: 1) loose subsidiarity policies in the 1980s and 1990s which would not have complied with the letter of the HAC, 2) stricter subsidiarity policies in the mid-2000s which come closer to compliance with the HAC and in some ways go beyond it, 3) subsidiarity policies which go far beyond the requirements of the HAC by the mid-2010s. India and South Korea have both mildly walked-back their subsidiarity policies since peak strictness in the mid-2010s,241 but not in ways significant enough to have a perceptible effect on statistical trends in those countries.

Late Twentieth Century: initial subsidiarity policies.

India and Colombia both expressed a mild preference for in-country placements in their initial subsidiarity policies, but both countries concentrated more on finding permanent family solutions than on prioritizing in-country placements in the 1980s and early 1990s.242 Though South Korea’s initial policies were strict on paper,243 the country’s extraordinarily high intercountry adoption numbers244 during this period suggest that South Korea’s initial approach to subsidiarity in the 1980s and 1990s was de facto similar to India and Colombia’s approaches.

2000s: moderate subsidiarity policies.

In 2006 and 2007, all three countries instituted policies which gave “due consideration” to in-country placements and therefore likely complied with the HAC’s subsidiarity requirements. Colombia’s 2006 policy gave preference to Colombian couples “all else equal”245 whereas India’s 2006 policy is textually slightly vaguer and presumably stricter mandating that “adoption agencies will give priority to in-country adoptions.”246 These two differing standards may make a difference in a case where a foreign family and a domestic family are both eligible to adopt and willing to adopt a child with disabilities, but the foreign family is better equipped to cater to the child’s specific special needs. According to a plain textual interpretation of both countries’ policies, the child would likely go to the foreign family in Colombia’s system, and to the domestic family in India’s. Whether either option would be in the child’s best interests would probably vary on a case-by-case basis. South Korea, by contrast, did not explicitly state a preference for in-country adoption, but rather restricted intercountry adoption by putting quotas into place among other restrictions and affirmatively encouraged in-country adoption in several ways.247 In addition to making preferences clear, India and South Korea also instituted domestic-adoption-only waiting periods. South Korea’s was five months, whereas India’s was initially one month or shorter, and are presently sixty days or shorter.248

Early 2010s: moderate to strict subsidiarity.

In 2011, both India and South Korea introduced their strictest subsidiarity policies, which go far beyond the subsidiarity requirements of the HAC, and Colombia followed suit in 2013. India’s 2011 policy put the 80:20 ratio into place, which coincides with the ratio of intercountry adoptions to total adoptions from India into the single digits without increasing in-country adoption numbers.249 South Korea’s 2011 Special Adoption Act does not appear to have overridden the 2007 policy, and on top of it, also put additional requirements on birth mothers before relinquishing their children and put “the foremost priority”250 on finding adoptive parents within Korea. It is worth noting that this act also did “walk back” previous restrictions in that it does not put any numerical quotas or caps on ICA, but statistics suggest that ICA numbers did not rise in the absence of quotas, 251 perhaps due to the strictness of the foremost priority standard. Colombia’s 2013 policy was stricter than previous policies,252 as well as stricter than both India and South Korea’s approaches in that it completely barred ICA for all except children with disabilities, older children, and children with siblings, and instituted exhaustive in-country search requirements for a child’s relatives before a child becomes adoptable.253

Recent years: some loosening, some tightening.

In the years since 2014, however, India and arguably South Korea have subtly retreated from their strictest interpretation of subsidiarity, while Colombia has maintained its strict approach. In loosening age requirements on couples of Korean descent, South Korea has widened the class of foreign prospective parents who are eligible to adopt,254 and in this sense arguably has loosened their definition of subsidiarity to a minor extent. India has taken more significant steps, by decreasing waiting periods for children with disabilities from sixty to fifteen days, and for other hard-to-place children from sixty to thirty days.255 Most significantly, India has also expanded the class of prospective parents who can adopt during waiting periods to include NRI and OCI Indians.256 However, looking at statistics from India and South Korea, neither country’s walking back of subsidiarity rules has had a perceivable effect on increasing intercountry adoptions, which have been in steady decline in both countries since the turn of the century.257 Colombia on the other hand has made its policies stricter since 2013, changing the age at which children become eligible for ICA from above seven to ten.258

Comparison of Present Policies

Looking at statistics, significant changes in intercountry and total adoption numbers appear to be correlated in some cases with developments in the law, and in other cases with current events. For example, the dramatic decrease in the percentage of intercountry adoptions during the 80:20 ratio in India, which rose immediately after the ratio was lifted, is possibly a direct result of this policy.259 On the other hand, the dramatic decrease in both total and intercountry adoptions in South Korea in the late 1980s is more likely connected to bad press than it is to any policy, as policy over those years was highly variable.260 A similar phenomenon was probably happening in Colombia in 2012, which saw a significant decrease in intercountry adoptions even though the law did not officially become stricter until 2013.261

Looking to present subsidiarity policies, this Comment compares differing approaches to diaspora adoptions, where each country falls in the subsidiarity debate about whether priority should be given over ICA to in-country foster families, and what percentage of total adoptions are intercountry adoptions. Firstly, each country takes a different approach to ICA by individuals with roots in the country who do not currently reside there. South Korea takes the strictest approach, only giving mild preference to those of Korean descent with slightly relaxed maximum age requirements.262 Colombia takes a middle ground approach, referring the pool of easy to place children to all Colombian citizens, regardless of whether they live abroad or in Colombia.263 Finally, India has the most relaxed approach treating adoptions by Indian citizens residing abroad as well as a large class of non-citizens of Indian descent (OCI cardholders) residing abroad as fully “at par” with adoptions by Indian citizens residing in India.264 Though India’s approach may violate the text of the HAC, it is arguably still compliant with the spirit of the convention in that it promotes the best interests of the child by allowing for flexibility on adoptions by individuals with roots in India, India may facilitate more permanent family solutions, and simultaneously avoid some of the identity-related harm connected to intercountry adoption.

On the issue of whether foster care should be prioritized over ICA, it seems likely that India and South Korea would, at least on paper, opt for ICA over domestic foster care, while Colombia may not. India is explicit that ICA takes precedence over nonpermanent solutions in-country.265 South Korea does not address this explicitly, but the language in the Special Adoption Law, which places “the foremost priority on finding adoptive parents in Korea first,”266 suggests that South Korea’s strong preference for in-country placement applies to adoption, and not to foster care. Colombia also does not explicitly address this, and there is evidence pointing in both directions. On the one hand, the language in the law governing adoption that refers to foster care stresses the temporary nature of this care.267 On the other hand, given that only children who fit into the “hard to place” category are eligible for ICA,268 presumably any children who are not “hard to place” would sooner go to indefinite foster care or institutionalization than to a permanent family abroad.

Of the three countries, South Korea’s approach is unique in that it has focused significant energy on affirmative policies which promote in-country adoption rather than policies which restrict ICA.269 This approach may have contributed to moderate success: the percentage of intercountry adoptions per year from South Korea now hovers around forty-five percent, compared to ninety-five percent in the 1980s, and sixty percent in the early 2000s.270 Looking at statistics however, the percentage of intercountry adoptions from India is far lower (around fifteen percent per year)271 than the percentage of intercountry adoptions from Colombia and South Korea (around forty-five percent per year).272 More research into why these numbers differ could be useful in helping understand how countries can increase in-country adoption, in addition to the types of affirmative policies which have worked in South Korea.

Conclusion

A case study of the subsidiarity practices over the past thirty years in India, Colombia, and South Korea suggest a general trend of countries implementing stricter and stricter conceptions of subsidiarity over time. At first glance, this appears to be a positive trend, and perhaps in some ways it is. The well-established record of illicit practices in intercountry adoption demonstrates why it is necessary to regulate ICA.273 Many adult intercountry adoptees have become strong critics of intercountry adoption because of the isolation they feel from their birth culture,274 which underscores the importance of placing children with culturally similar families when possible.

On the other hand, the case studies demonstrate that the strictest implementations of subsidiarity policy often undermine the protections they seek to put in place. In India, a court blatantly side-stepped CARA to approve an ICA where in-country placements had not been considered due to reasonable exasperation at excessive bureaucratic delays in approving intercountry adoptions.275 The current Colombian system, which requires exhaustive family searches, is so strained that new arrivals to orphanages are sometimes not fully evaluated for adoption eligibility.276 Finally, in South Korea, birth mother registration requirements, which attempt to protect an adoptee’s identity rights, resulted, even if indirectly, in more babies being deposited in the country’s infamous baby boxes.277 Incidents like these suggest that countries designing subsidiarity policies should consider whether a given regulation puts so much strain on the system that it ultimately undermines the very protections it seeks to put in place.

If subsidiarity were working as it should, countries would not have to affirmatively restrict ICA, because the numbers would decrease on their own due to more children being parented by their birth families and adopted domestically. Since the mid-2000s, ICA has massively decreased, both in the case study countries, and globally. Statistics suggest this is not due to a lack of adoptable children. In India in 2018, 4,027 children were adopted, out of a total of 370,000 children living in childcare institutions (about one percent).278 In Colombia in 2019, 1,390 children279 were adopted, out of a total of over 25,000 children280 living in institutions (around five percent).281 In both cases, it is important to note that these numbers may also be due in part to fewer prospective adoptive parents given the rise of surrogacy, which has increased significantly as adoption has decreased.282

The goals of subsidiarity are commendable. In an ideal world, birth mothers would have all the support they need to raise their children and would not be forced to give them up due to poverty or social stigma. In an ideal world, all unparented children could be expeditiously placed in loving permanent homes within their country of birth. Supporting birth mothers and developing a robust in-country adoption infrastructure should absolutely be a foremost priority for sending countries. Given the fact that demand and the prospect of financial gain from receiving countries have often been drivers of illicit practice,283 historical receiving countries too bear responsibility in supporting sending countries as they pursue these goals. What is often missed, however, is that pursuing subsidiarity does not have to go hand in hand with restrictions on ICA.

Katharine H.S. Moon argues that South Korea has gone wrong in that it organizes its policies around improving its image and “appeasing” adult intercountry adoptees from Korea, who are often the fiercest critics of ICA in the Korean context.284 Though Moon was speaking about South Korea alone, this critique can be levied in large part at India and Colombia as well, which, in restricting ICA beyond what the HAC requires, have arguably prevented at least some children from finding permanent families. Moon aptly highlights that “policies that encourage single women to keep their children and [encourage in-country adoption] can coexist with policies that facilitate international adoption.” As these countries and others consider new strategies on how to best implement subsidiarity, they should be aware that promoting in-country adoption and complying with the HAC is completely possible without unduly restricting ICA when it represents the best chance that a child has of finding a permanent loving home. An approach to subsidiarity which affirmatively encourages in-country adoption without artificially restricting ICA has the double benefit of complying with the subsidiarity requirements of the HAC and promoting the best interest of the child.

- 1Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption, opened for signature May 29, 1993, T.I.A.S. No. 08-401 (entered into force Apr. 1, 2008) [hereinafter Hague Adoption Convention].

- 2Id.

- 3See Status Table, Hague Conference on Private International Law, https://perma.cc/UL7N-77GP [hereinafter HCCH Status Table] (last visited Jul. 28, 2023).

- 4See generally Chad Turner, A History of Subsidiarity in the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, 16 Chi.-Kent J. Int’l & Comp. L. 95 (2016).

- 5Elizabeth Bartholet & David Smolin, The Debate, in 1 Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices, and Outcomes 370, 384 (Judith L. Gibbons & Karen Smith Rotabi eds., 2012).