International Law Adrift: Forum Shopping, Forum Rejection, and the Future of Maritime Dispute Resolution

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is the primary international agreement governing maritime law. It incorporated a feature that, at the time, was considered to be on the leading edge of international legal development: a binding dispute resolution system. At the time of accession, each state party was required to select one of four available forums: the International Court of Justice, the newly created International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea, private arbitration, or special tribunals convened to resolve unique scientific and environmental matters.

Since the Convention went into effect in 1994, however, states have made little use of the system; many have resolved issues through private negotiation or have simply allowed legal conflicts to endure. Moreover, less than a quarter of parties to the 1982 Convention have selected a preferred forum. Among the relatively small set of cases that have been heard, however, patterns have begun to emerge that contain hints about how states engage in forum shopping in the maritime context.

This Comment conducts a comprehensive analysis of existing case law and tests various academic theories about forum shopping to determine why states opt for each of the various courts or tribunals when submitting a dispute for resolution under the Convention. It finds that subject matter is the best predictor of forum selection, as each forum has made use of comparative advantages to gain a foothold in particular areas of the law. The Comment also notes a worrying trend in non-participation by major powers, including Russia, China, and the U.S. If the great powers of the world reject the compulsory nature of the system, UNCLOS will become less effective at channeling tensions into peaceful resolutions. This will increase the risk that states will resort to the use of force to solve disputes.

I. Introduction

Imagine: In 2019, maritime disputes in the East and South China Seas remain unresolved. As part of the promised renegotiation of the “trade deal” between the U.S. and China, Washington agrees to discontinue its military patrols in China’s near seas in return for a Chinese agreement not to pursue trade remedies at the World Trade Organization (WTO) for new American tariffs on manufactured goods. The Philippines and Thailand are firmly ensconced in the Chinese sphere of influence: American ships no longer call in their ports and Chinese cash flows to the bank accounts of their politicians. Vietnam and Japan continue to resist Chinese dominance in the Asian littoral, but their cause seems more dire by the day. China declares large parts of the high seas off-limits to foreign militaries and subjects foreign-flagged commercial vessels to arbitrary inspections.

In an effort to appeal to the international community, Tokyo and Hanoi file legal claims under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or Convention), the premier international agreement governing such disputes.1 When it was first negotiated in 1982 and finally came into effect in 1994,2 UNCLOS’s various features, including its binding dispute resolution system, were considered to be at the leading edge of international law.3 Part XV of the Convention offers several choices of forum to resolve disputes.4 How, then, might a state strategize to pick the optimal forum? Did any of the countries involved select a preferred venue when they ratified the Convention? Is there any forum that is particularly well suited to this area of maritime law? Might any one type of procedure give the petitioners an advantage?

This particular dispute, however, comes with a twist. Recalling how China ignored an adverse arbitral award by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in 2016,5 Japan and Vietnam take their cases to internationally established courts: the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Both claims succeed on the merits, and the courts issue strong condemnations of China’s actions. However, following the precedent it set before and the pattern of behavior of the world’s other major military powers, China maintains course. The Convention, which represented the culmination of centuries of legal developments to open the seas to all, has no effect on the sudden closure and balkanization of shipping lanes in East Asia.6

This scenario may never come to pass. Countries regularly make use of UNCLOS’s advanced, binding dispute resolution system. At the time of writing, eight cases are pending before three separate bodies under the Convention, contributing to a budding field of case law interpreting and applying the Convention that has developed over the past two decades. Although scholars have analyzed the forum selection process,7 several new developments have occurred within the last few years that necessitate another look. Tribunals have begun to emerge from the niches they created for themselves early on, and individual states have experimented with using more than one forum to resolve longstanding debates with their neighbors.

However, the future is uncertain. The U.S. has never ratified the Convention due to domestic opposition.8 Meanwhile, Russia and China, both signatories for nearly two decades,9 have rolled back their commitment to international legal tribunals by refusing to participate in the binding resolution of disputes—or even the proceedings that produce those resolutions—in the last four years.10 As the three largest military powers in the world and most important actors in the U.N. Security Council, their continued opposition to the Convention creates a worrying trend for international law. Their refusal to abide by judgments issued by legally constituted forums sets a precedent for smaller nations to disregard binding rulings, relegating the Convention’s method of resolving disputes to obscurity and encouraging powerful states to impose terms on their weaker neighbors.

This Comment conducts a comprehensive examination of every case decided under Part XV to date. Section II briefly reviews the development of international maritime law in the modern era. It argues that the law has attempted to balance the interests of both coastal states and shipping nations over the course of time, but that the current rules have swung in favor of coastal states. Section III presents an overview of the Convention as it exists today. It summarizes the cases decided under Part XV and evaluates various theories on how states shop for the best forums against the record of cases that has accumulated over the past two decades. It finds that the forum selection process that the framers of the Convention designed has little effect on actual practice. Instead, international legal tribunals have gained subject-matter expertise in narrow areas of law that are frequently litigated, while all other subject areas usually default to arbitration. Section IV identifies the most notable trend in the system’s recent past: forum rejection. Several major military powers have refused to participate in legal proceedings under Part XV, rejecting the jurisdiction of any forum over certain issues. This trend creates a serious problem and is likely to lead to less reliance on binding dispute resolution, leaving disputes to linger and incentivizing powerful states to intimidate their weaker neighbors to achieve their goals. In light of continued American opposition to international legal dispute resolution mechanisms, this trend may continue unabated.

II. Mare Liberum: 400 Years of Open Seas

For more than two thousand years, Western law has recognized that the oceans and other waterways are res communes—things that are common to all persons and therefore incapable of being owned.11 Justinian observed that “the air, running water, [and] the sea” are “by natural law common to all.”12 The natural division between private and communal property respects the unique characteristics of waterways and their critical role in socially beneficial commerce:

By keeping waterways in the commons . . . the law facilitate[s] transportation between owners of different parcels of private property. To allow any person to privatize a [waterway] would disrupt these valuable forms of interactions, which would then paradoxically reduce the value of all private properties that lie along the commons.13

However, the law’s commitment to such a system has wavered over the centuries. For example, in seventeenth century Germany, several small fiefdoms arose along the length of the Rhine; each charged its own tax, which “cut sharply into [the river’s] value for transportation and commerce.”14 The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 solved the problem by explicitly banning the imposition of tolls and reopening river commerce for the benefit of the whole society.15

Although the principle of free navigation of the seas dates back millennia, the modern law of the sea began with the resurgence of European shipping in the seventeenth century. In 1608, Hugo Grotius published the Dutch position in his seminal work, Mare Liberum.16 Writing in response to Portuguese efforts to close trade routes to the East Indies to other European nations, Grotius insisted that the nature of the oceans made it illegitimate for any state to claim their sovereign control.17 The core of his argument recalled the Roman understanding of natural law, arguing that “freedom of trade is based on a primitive right of nations which has a natural and permanent cause; and so that right cannot be destroyed.”18

Grotius’ counterpart in England, John Selden, replied with Mare Clausum in 1635.19 Although Grotius’ arguments were primarily aimed at expansive Spanish and Portuguese claims, Selden noted that England’s claims to the waters surrounding it would be defeated by Grotius’ ideas. Selden insisted that “the sea . . . is not common to all men, but capable of private dominion or property as well as the land.”20 The King of Great Britain, he argued, “is lord of the sea flowing about, as an inseparable and perpetual appendant of the British Empire.”21 These two positions form the poles of a debate that continues into the present day, often providing the fuel for maritime disputes between states.

Customary international law adopted an intermediate rule that attempted to satisfy the interests of both commerce and coastal states.22 Until well into the twentieth century, coastal states enjoyed territorial sovereignty up to three nautical miles from their shores. Calculated roughly to match the maximum effective range of cannons,23 the rule gave states a buffer with which to protect their beaches and ports without unnecessarily impinging on the freedom of navigation in the open ocean.24

The pace of legal development and codification accelerated throughout the twentieth century. Following the First World War, American President Woodrow Wilson demanded “[a]bsolute freedom of navigation upon the seas” as the second of his Fourteen Points (ranking just after “open covenants of peace” in his priorities).25 The 1930 Hague Conference on the Codification of International Law made an abortive attempt at clarifying customary law, but it was not until the U.N. took up the effort after the Second World War that the process yielded the modern law governing the oceans.26

Today, the legal principles of free navigation of the seas and respect for coastal states’ prerogatives take shape in the principal international agreement on maritime law, UNCLOS.27 The First Convention (UNCLOS I) met in 1958 and produced a number of generic documents but failed to delineate specific provisions for a comprehensive agreement.28 UNCLOS II convened two years later and failed to reach agreement on the breadth of the territorial sea and limits on fisheries, two items left unresolved at the first conference.29

The 1973 Convention (UNCLOS III) finally produced a comprehensive international agreement on maritime law. Completed in 1982, it departed from customary law by establishing greater protections for coastal states. The framework extended the territorial sea to twelve nautical miles—four times what it had been for the previous several centuries.30 It also established a twelve nautical mile contiguous zone beyond the territorial sea, in which a coastal state may “prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration, or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial seas.”31 Most notably, the Convention established an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends 200 nautical miles from the shore (when space provides).32 The EEZ grants coastal states “sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving, and managing[] natural resources, whether living or non-living.”33 Such activities include “(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures; (ii) marine scientific research; [and] (iii) the protection and preservation of the marine environment,” among others.34 The establishment of EEZs drastically increased the amount of ocean space that was subject to some level of sovereign control by coastal states; by one estimate, EEZs now cover 43 million square nautical miles, which amounts to 41 percent of the area of the world’s oceans or the approximate equivalent of the total area of the world’s landmasses.35

These are merely a few examples of the developments in maritime law that UNCLOS brought about that provide context for the scope of the rights involved when states are unable to resolve their differences in interpretation and application of the Convention. Fortunately, the Convention also created a novel solution to this challenge—a binding dispute resolution system.

III. Binding Dispute Resolution

During the negotiation of the Convention, several parties demanded the inclusion of a binding dispute resolution system to prevent the use of force or intimidation in questions over the interpretation and application of UNCLOS’s terms.36 Developed Western powers, including the U.S., were uncomfortable with the departures from customary maritime law and believed that a number of disputes would arise over them; a binding system to resolve those disputes was critical to their acquiescence. Conversely, smaller, less powerful nations were equally enthusiastic about the system, which they viewed as a tool they could employ against their larger neighbors. The system’s inclusion was “viewed as necessary to balance the interests of all states against the increased jurisdictional competences given to coastal states by the Convention.”37 At the time, such a system was considered “innovative and far-reaching,” and observers had high hopes for its future.38

A. The System’s Design

The core function of the system is to dissuade parties from resorting to the use of force to solve their problems and, instead, encourage resolution “by peaceful means.”39 Codified in Part XV of the Convention, the system establishes a number of obligations for parties to fulfill prior to referring a dispute. These include an exchange of views between the parties to clarify the extent of the dispute and observation of any other compulsory mechanisms that exist in separate agreements between them.40 After fulfilling these obligations, states face a unique and novel decision: which forum should hear the case?

UNCLOS offers four separate options to answer that question.41 First, the Convention established a new judicial body specifically to apply its law: the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS).42 ITLOS is empowered to hear any dispute arising under the Convention, and it has special jurisdiction for two claims: provisional measures under Article 290 and the prompt release of detained vessels and their crews under Article 292.43 Second, parties may refer their disputes to the ICJ,44 which may apply both UNCLOS and any other authority that is available under the ICJ’s jurisdiction-granting statute.45 Third, the parties may opt for arbitration under Annex VII of the Convention.46 Although the parties enjoy the choice of a range of arbitral bodies, twelve of the thirteen arbitral cases raised so far have been heard under the auspices of the PCA.47 Lastly, parties may opt for special arbitration under Annex VIII.48 These cases are confined to a narrow field of highly technical disputes over “(1) fisheries, (2) protection and preservation of the marine environment, (3) marine scientific research, or (4) navigation, including pollution from vessels and by dumping.”49

Article 287 calls for States Parties to select a preferred forum to hear their disputes at the time of accession to the Convention.50 In the event that a dispute arises between parties that selected different preferred forums (or that have failed to make a selection), the case defaults to Annex VII arbitration.51 Even if both parties have selected the same forum, they may agree to pursue the case elsewhere.52 States may change their forum selection at any time, although a new selection does not affect ongoing proceedings.53 Countries may choose more than one forum and may rank them in order of preference as well.54 At the time the Convention was negotiated, “a choice of forum was said to be of critical importance to acceptance of the proposed dispute settlement system.”55

However, forum selections have not developed in the way that the framers of the Convention envisioned. Although states are required to select a choice of procedure under Article 287, only forty-three have done so (approximately 25 percent of all signatories).56 Moreover, disputes often end up in forums other than those that states have chosen because they agree to take the issue to another forum or because the parties cannot agree and default to Annex VII arbitration.57

B. A Summary of the Case Law

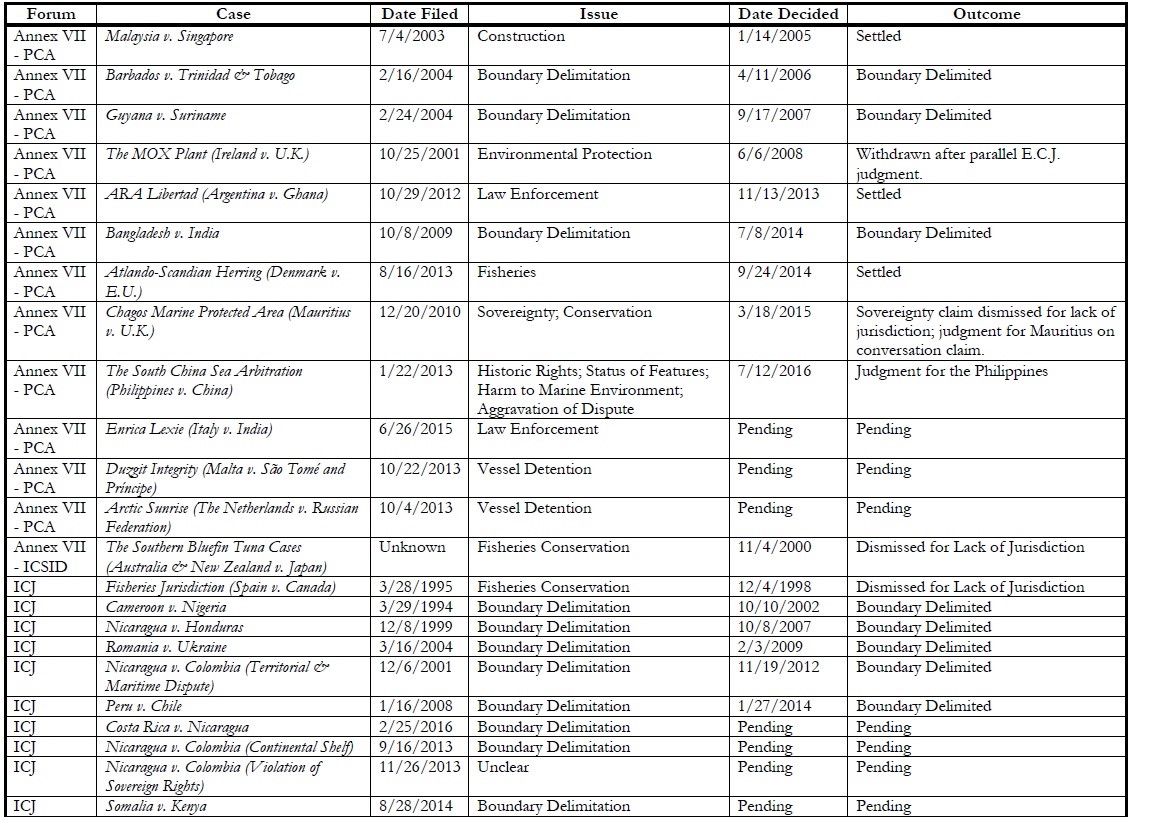

At the time of writing, forty-five cases have been submitted under Part XV since UNCLOS came into effect in 1994, averaging just two per year.58 Earlier studies have catalogued those cases to some degree, but nearly ten years have passed since those prior efforts.59 In the meantime, several new cases have arisen that have carried the development of the law into new territory, particularly with respect to questions of jurisdiction. In order to evaluate existing theories of forum selection, it is helpful to review trends in the case law to date. The Appendix provides a table of the cases that may be useful to the reader. This Section evaluates the cases by three categories: forum, subject matter, and participating states.

1. States Parties have four options when selecting a forum under Part XV.

Since the Convention established ITLOS in 1996, it has heard the lion’s share of disputes with twenty-one cases.60 ITLOS possesses a unique power to issue advisory opinions interpreting the Convention, but it has exercised that authority only twice.61 ITLOS has three comparative advantages over its counterparts in obtaining jurisdiction over Part XV cases. First, it has sole jurisdiction under Article 290 to impose provisional measures on parties while their cases are pending arbitration under Annex VII or Annex VIII.62 Akin to preliminary injunctions in courts of the U.S., these orders “have frequently helped the parties to settle a dispute,” enabling ITLOS to facilitate the resolution of a dispute even when the parties opt for arbitration.63 Second, it has sole jurisdiction to hear controversies involving the prompt release of detained vessels and crews under Article 292.64 In its first decade of operation, ITLOS heard cases about detainment more than disputes over any other subject (nine in total), although it has fielded only one such case since 2007.65 Third, unlike arbitral tribunals, ITLOS proceedings are free to signatories to the Convention,66 and so are attractive to countries that may otherwise not be able to afford arbitration.

As the second option for parties, the ICJ has heard ten cases under UNCLOS since 1994.67 Because it exists apart from the Convention and has its own authorizing statute, the ICJ has a comparative advantage over ITLOS in that it can apply other substantive sources of international law besides UNCLOS.68 For example, in 2012, when the ICJ resolved a dispute over the delimitation of the continental shelf between Colombia and Nicaragua, it applied Article 76 as customary international law even though Colombia is not a signatory of UNCLOS.69

The third available forum, Annex VII arbitration, has been dominated by the PCA at The Hague; it has heard twelve of the thirteen such cases.70 As the default forum under Article 287, most cases arrive at the PCA because the parties cannot agree to bring the case elsewhere.71 Observers have suggested a few other theories about why states might opt for arbitration rather than an international judicial body, including domestic opposition to supranational courts and affinity for arbitral procedures that are closer to common law states’ own judicial procedures.72

The final option, Annex VIII, which creates special arbitration for scientific and technical matters, has never been used.73 As a result, this Comment offers no analysis on the subject.

2. Subject matter is often the determining factor in forum selection.

An analysis of the cases by subject matter presents a useful opportunity to compare the frequency with which different forums hear similar types of cases. Some trends comport with the text of the Convention. For instance, ITLOS hears every law enforcement “prompt release” case under Article 292 because the Convention grants ITLOS sole jurisdiction over those matters.74 Parties with cases tangentially dealing with the detention or confiscation of ships but not covered under Article 292 also tend to choose ITLOS as a forum because of its subject matter expertise in the field, even though those cases may not fall within ITLOS’s exclusive jurisdiction. These include cases in which vessels have already been released and parties seek damages for alleged violations of the Convention.75 However, in other matters, such as boundary delimitation, there appears to be some competition between the forums for business.76 Additionally, as noted above, states often make use of the provisional measures option under Article 290 to invoke the jurisdiction of both ITLOS and the PCA in the hopes that one or both will render a favorable ruling.77

a) Law enforcement

Eighteen cases have arisen under Part XV regarding enforcement of either international or domestic laws against foreign-flagged vessels operating in EEZs. These are more numerous than disputes on any other subject. Because of its sole jurisdiction to hear “prompt release” cases under Article 292, ITLOS has heard fifteen of the disputes (nearly 85 percent). As the only tribunal developing the law in this area, ITLOS has had free reign to establish rules to govern the release of vessels that are detained for alleged violations, allowing flag states to post a security bond in return for their ships and crew members while pledging to return the suspects when the time for trial arrives.78

In the first case it heard, M/V Saiga, ITLOS established a legal framework for evaluating the issues at the center of most disputes—the calculation of the proper amount for the security bond.79 After ITLOS affirmed the rule in its second “prompt release” case, Camouco, the cases immediately began to dwindle.80 ITLOS decided its last “prompt release” case in 2007, though another is pending resolution.81

More recently, ITLOS has served as the preliminary court to impose provisional measures before referring law enforcement matters to the PCA under Annex VII.82 These cases include ARA Libertad, in which Ghana detained an Argentinian warship,83 and Arctic Sunrise, in which Russia arrested Greenpeace members protesting an oil platform and impounded their vessel.84 In both instances, ITLOS imposed provisional measures for release of the vessels and crew before referring the cases to the PCA to consider violations of the law and corresponding damages.

In contrast to the high volume of law enforcement cases that ITLOS has adjudicated, the PCA has heard only three. Two of those were ARA Libertad and Arctic Sunrise, in which ITLOS first imposed provisional measures; ARA Libertad settled before the PCA could rule,85 while Arctic Sunrise saw one party refuse to participate, allowing the PCA to reach a final judgment on the merits that largely followed ITLOS’s preliminary opinion.86 The third case, Duzgit Integrity, remains pending.87

b) Boundary delimitation

In contrast with ITLOS’s dominance in law enforcement matters, the ICJ has done the bulk of the work on maritime boundary delimitation. It has heard eight of the twelve cases brought under Part XV, with many involving land boundaries as well as maritime borders.88 For this reason, the ICJ seems to be the best situated venue to delimit boundaries; its ability to decide issues outside the maritime context allows states to settle their disputes with their neighbors in a single sitting rather than separating the land and sea cases in separate forums. Clive Schofield, Director of the Australian Centre for Ocean Resources and Security at the University of Wollongong, posited that the ICJ’s work in boundary delimitation predates UNCLOS, providing a rich body of precedent on which to draw that the other forums lack.89 The ICJ has made use of its dominant position in the international legal environment on multiple occasions to declare sections of UNCLOS to be customary international law and therefore binding on signatories.90

In recent years, the other forums have also participated successfully in boundary delimitation cases. The PCA delimited maritime borders between Barbados and Trinidad & Tobago in 2006,91 Guyana and Suriname in 2007,92 and Bangladesh and India in 2014.93 ITLOS resolved a border dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar in 2012.94

c) Fisheries and environmental protection

The remaining cases do not fall neatly into any one category, and have accordingly been distributed fairly evenly among the tribunals. ITLOS is the only forum that has successfully issued any kind of order in a case involving fisheries. There have been five cases to date, and all five eventually settled before a judgment on the merits (three for ITLOS, one for the PCA, and one for the ICJ). In the Southern Bluefin Tuna Cases, ITLOS imposed provisional measures on Japan when it allegedly exceeded its fishing quotas by creating a scientific experiments program that necessitated catching extra tuna.95 However, the parties settled the matter in advance of Annex VII arbitration.96 Four cases (covering two disputes) have focused primarily on environmental protection. In The MOX Plant, Ireland successfully petitioned ITLOS to impose provisional measures on the construction of a new nuclear power plant in the U.K.97 The case was later dropped before a PCA ruling because of changes in E.U. law that left the issue moot.98 A similar process occurred in Malaysia v. Singapore: ITLOS imposed provisional measures on land reclamation projects in the Straits of Johor, but the parties settled the matter prior to an arbitral award.99

The final two cases do not fit neatly into any single category. In Chagos Marine Protected Area, Mauritius argued that it, and not the U.K., should be considered the coastal state for all rights arising under UNCLOS with respect to the Chagos Archipelago, home to the British and American military base at Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean.100 The dispute arose from Britain’s lease on the islands for military purposes; Mauritius suggested that it should govern the fisheries and other maritime resources in the islands’ EEZ, which Britain argued would interfere with its lease.101 The PCA punted the issue, finding that UNCLOS could not answer questions of sovereignty but agreeing with Mauritius that Britain had a duty to preserve the natural resources for the eventual return of control to Mauritius.102 The second case, The South China Sea Arbitration, is a uniquely famous case that is discussed at length in Section IV(B).103

Early in the age of Part XV, Sicco Rah and Tilo Wallrabenstein of the Law of the Sea and Maritime Law Institute at the University of Hamburg suggested that ITLOS would take on a special role in the field of environmental protection through its unique authority to issue advisory opinions that would guide the development of the law.104 The cases, however, do not support that theory. ITLOS has participated in cases involving the environment only as the forum for provisional measures, while the parties selected arbitration to issue rulings on the merits. Likewise, ITLOS has issued only two advisory opinions; only one had any connection to environmental protection.105 Finally, there has been some modern criticism of ITLOS’s decisions in “prompt release” cases. Some observers believe that ITLOS tends to impose undervalued security bonds for violating vessels to obtain their release from detention, in effect lowering the deterrent for crimes like poaching protected fish.106

3. Certain petitioning states exhibit preferences for particular forums, but Article 287 has little impact on forum selection.

This Section will provide a brief comment on the interaction between Article 287 choice of procedure selections and the actual behavior of parties when selecting a forum.107 Of the twenty-eight states that have brought cases under Part XV in any forum, only eleven had previously selected a preferred forum. Of those eleven, six ended up in a forum other than the one they preferred. Five states followed the default pattern of using Annex VII arbitration in the event that the two parties could not agree: Argentina and Ghana, Bangladesh and India, Denmark and the E.U., Italy and India, and The Netherlands and Russia. In one case, because the defendant had not signed onto UNCLOS, the case defaulted to the ICJ as the only forum that had jurisdiction over both parties (Chile and Peru).108

There are two other interesting items to note. First, as might be expected, those countries that specialize in acting as flag states for commercial vessels, such as Panama and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, frequently appear before ITLOS in the context of petitioning for prompt release of their vessels or damages after the fact.109 Similarly, Nicaragua has become a frequent petitioner at the ICJ. It brought four of the ten cases the ICJ has heard under UNCLOS (Honduras and multiple disputes with Colombia) and appeared as the respondent in a fifth case in which Costa Rica is the petitioner.110

C. Theories on Forum Shopping

Scholars have posited a number of theories to explain how states go about shopping for a forum under Part XV. However, no study within the last decade has updated those theories in light of new cases to test their accuracy. This Comment will attempt to do so. While some theories, such as that selection is based on the subject matter at issue, have strong support. Others are less helpful in predicting where a case will be filed.111

1. Scholars offer a number of useful theories that remain relevant and informative.

First, the framers of the Convention assumed that states would select forums using the choice of procedure under Article 287, which would decide the issue of forum shopping at the time of accession and provide a stable framework for determining the proper venue ex ante. As noted above, this concept was not realized. However, ITLOS Judge Tullio Treves has suggested that the fact that few states parties have submitted Article 287 selections does not necessarily represent widespread disapproval of the dispute resolution system or ITLOS in general.112 He points out that, of those states that have made the selection, the vast majority opted against arbitration.113 Given his position, he takes that fact as a heartening sign for the acceptance of international courts over arbitration.114 However, as described earlier, Article 287 selections have determined the forum in just five cases over twenty years.115

Second, some scholars have suggested that procedural differences can explain affinities for arbitration over other venues. Rah and Wallrabenstein note that arbitration seems to have been the preferred procedure in cases that are eligible to go elsewhere (contingent on the agreement of both parties), even though the cost of resolving the dispute at ITLOS is usually lower than the cost of arbitrating it.116 They explain the puzzle by noting the advantages of arbitration. First, arbitration is more acceptable to domestic public opinion, especially for the losing country.117 Adverse rulings by international legal tribunals sometimes provoke a public backlash against participation in agreements that the public perceives as a cession of sovereignty to a supranational body; arbitration tends to avoid such optics.118 They also note the increased confidentiality available in arbitration and the bar to third party intervention that does not exist at ITLOS or the ICJ.119 In the ten years since Rah and Wallrabenstein published their comments, arbitration has continued to draw the majority of petitions that are eligible to be heard outside ITLOS and that do not involve boundary delimitation.

Finally, Professors Emilia Powell and Sara Mitchell recently introduced interesting quantitative research suggesting that there is a correlation between the type of domestic legal system a state employs and its forum under Part XV.120 They argue that common law countries have a strong aversion to the ICJ and prefer arbitration because it mimics the common law system in several respects.121 Conversely, civil law countries are more likely to opt for the ICJ and ITLOS because “the similarities between legal rules of the ICJ [and ITLOS] and the civil law tradition enhance civil law states’ comfort levels in working with the World Court.”122 The thesis is novel and deserves further analysis, but that effort is outside the scope of this Comment.

2. Other conclusions arise from the cases.

While instances of forum selection may not have played out exactly as the framers of UNCLOS might have imagined, Part XV has grown into a robust dispute resolution system with important contributions to the development of international maritime law. The system seems to have developed a comprehensive normative framework for the resolution of certain types of disputes by establishing clear rules that reduce transaction costs and facilitate bargaining among parties ex ante rather than invoking Part XV.123 UNCLOS has made particular strides of this sort in the areas of prompt release cases, evidenced by successful resolution of a number of early cases, the development and application of a set of clear and consistent rules, and a subsequent decline in frequency of similar disputes.124

However, the most important development since the last round of studies a decade ago has been the emergence of a counter-movement by the great powers of the world. This phenomenon adds a layer of complexity to forum shopping for any country considering bringing a claim against a powerful neighbor: even if a complainant selects the most advantageous forum for its grievance, will its opponent agree to participate in resolving the issue? More importantly, even if the complainant wins on the merits, will the state subject to the judgment change its behavior?125 The current trend suggests that the answer to both questions is no, which poses a problem for the survival of the binding dispute resolution system.

IV. Refusal to Participate and the Future of the System

In the more than two decades since UNCLOS entered into effect, its system of resolving disputes between States Parties has achieved great success in regulating a number of fields of maritime law. Nine disputed maritime borders have been finalized and seven vessels and their crews have been released on bond after detention in a foreign country. More important than the resolution of each individual dispute, the various forums have begun to establish rules that govern each type of situation, allowing parties to avoid dispute resolution by bargaining in light of established guidelines.126 However, the past few years have seen States Parties that once abided by the rules and norms of UNCLOS begin to refuse to participate in the dispute resolution process. Because the refusing parties are also the world’s preeminent political and military powers, non-participation raises serious concerns about the efficacy of the system and its future.

A. The Russian Federation

The Russian Federation, then the Soviet Union, was one of the initial signatories to the Convention in 1982.127 It ratified UNCLOS in 1997, three years after the treaty went into effect.128 Both at signing and again at ratification, Russia appended declarations refusing to submit to binding dispute resolution procedures in a number of situations, including “disputes concerning . . . sea boundary delimitations . . . [or] law-enforcement activities in regard to the exercise of sovereign rights or jurisdiction.”129 It is one of only forty-eight countries that have been involved in the resolution of a dispute, appearing before ITLOS three times: the first as a plaintiff and two other times as the defendant.130

In some sense, Russia’s involvement with the system represents a model of how the process should work: each case struck a balance between the needs of both States Parties while attempting to maintain a consistent legal framework. However, Russia was also called to appear before the PCA in an Annex XII case in 2013, after it adopted an unusual position that marked a turning point in the development of the dispute resolution system.

1. Russia largely abided by its commitments in earlier cases.

This Section examines Russia’s initial interactions with binding dispute resolution under UNCLOS. In its first three Part XV cases through 2007, the Russian Federation largely abided by its duties under Part XV and had a mixed record of success before ITLOS.

a) The “Volga” case131

In February 2002, Australian military personnel aboard HMAS Canberra boarded the Volga, which was a Russian fishing vessel allegedly fleeing Australia’s EEZ.132 After Australian authorities detained the ship in Fremantle for violations of domestic fishing laws, they charged three Spanish crewmembers with criminal offenses and released them on bail.133 The Russian government filed an application with the ITLOS under Article 292 to obtain the prompt release of the vessel and her crew in return for a security bond.134

The case was the fourth time ITLOS heard a dispute under Article 292, and it adhered closely to the legal standards it had previously established to determine the reasonableness of a security bond.135 In a victory for Australia, and for the dispute resolution procedures, ITLOS determined that Australia had requested a reasonable bond and ordered Russia to make the payment in order to obtain the release of the vessel.136 The case was particularly noteworthy among international legal proceedings for its quick three-week completion.

b) The “Hoshinmaru” Case (Japan v. Russian Federation)

The first of two companion cases before ITLOS in 2007, Hoshinmaru, stemmed from the Russian detention of a Japanese fishing vessel following a routine inspection in the Russian EEZ.137 Although the vessel was licensed to fish in the area, the inspection uncovered a cache of sockeye salmon that the fishermen were attempting to pass off as chum in violation of Russian regulations.138 The Russian Coast Guard detained the vessel in Petropavlovsk and Japan filed an application with ITLOS under Article 292 for its prompt return.139 Before ITLOS considered the application, Russia set a bond of approximately $980,000 USD, representing both the value of the boat and estimated damages to the salmon population. Japan alleged that the amount was unreasonable and requested ITLOS’s assistance in resolving the issue.140

The situation differed from Volga in one key respect. In that case, Australia set the amount for the security bond soon after the detention of the vessel in accordance with Article 73 of the Convention. ITLOS stepped in at Russia’s request, but it found the bond to be reasonable and merely facilitated the transaction. In Hoshinmaru, however, Russia waited weeks to respond to Japanese requests for a bond; it only named a figure once Japan invoked ITLOS’s aid.141 In its judgment on the merits, ITLOS struck down the $980,000 as excessive and reduced the amount to approximately $445,000.142

c) The “Tomimaru” Case (Japan v. Russian Federation)

The second of the two cases of 2007 turned out better for Russia. As in Hoshinmaru, the problem involved the detention of a Japanese vessel for illegal fishing in the Russian EEZ. However, because the particular offenses were much more egregious by the standards of Russian domestic law (tons of illegal fish caught and fraudulently concealed in the ship’s logs), local law enforcement officials obtained a court order to confiscate the vessel as evidence in their prosecution in the matter.143 The decision was litigated as far as Russia’s Supreme Court, which upheld the confiscation.144 Japan requested ITLOS’s assistance, but ITLOS refused to intervene.145 It found that Russia had properly resolved the matter in its own courts, and that any involvement on its part would “contradict the [domestic] decision . . . and encroach upon national competences, thus contravening Article 292.”146

2. Russia adopted a new approach in Arctic Sunrise (The Netherlands v. Russian Federation).

With three previous appearances before ITLOS, Russia had become one of the most frequent participants in Part XV proceedings by 2007. However, concurrent with other changes in its foreign policy, Russia took a new approach the next time representatives of ITLOS came calling. In September 2013, the Arctic Sunrise, a Dutch vessel chartered by Greenpeace, staged a protest of the Russian oil platform Prirazlomnaya in the Russian EEZ in the Pechora Sea.147 The Russian Coast Guard seized the ship, towed it to Murmansk, and arrested the crew. In response, the Netherlands, as flag state of the vessel, sought a prompt release under Article 292. When Russia disregarded the request, the Netherlands filed an application for provisional measures under Article 290 with ITLOS, to include the release of the vessel and its crew.148 It also filed a subsequent application for Annex VII arbitration to determine both the legality of Russia’s actions and monetary damages with the PCA.149

Unlike in previous instances, Russia balked. In a note verbale addressed to ITLOS, Russia recalled the declaration it made in 1997: “[Russia] does not accept procedures provided for in Section 2 of Part XV of the Convention, entailing binding decisions with respect to disputes . . . concerning law-enforcement activities in regard to the exercise of sovereign rights or jurisdiction.”150 It notified ITLOS that it did not accept ITLOS’s jurisdiction to hear the case and would not participate in the proceedings.151 ITLOS thus faced a difficult question: what to do when a State Party does not appear in court?

The Netherlands responded with a novel legal argument. It suggested that declarations such as the one that Russia made can deny jurisdiction only over those matters of which the Convention allows a coastal state to opt out.152 The declaration arose under Article 298, which allows states to opt out of jurisdiction for “disputes concerning law enforcement activities in regard to the exercise of sovereign rights or jurisdiction excluded from the jurisdiction of a court or tribunal under Article 297, paragraph 2 or 3.”153 Article 297, paragraph 2 provides that “a coastal state shall not be obliged to accept the submission of [a dispute regarding marine scientific research]” arising out of other sections governing the conduct of such research within a state’s EEZ.154 Paragraph 3 provides the same right to coastal states in disputes over fisheries within their EEZs.155 Because this dispute had nothing to do with research or fishing, the Netherlands argued, Russia’s declaration ran into a barrier erected by Article 309:156 “No reservations or exceptions may be made to this Convention unless expressly permitted by other articles of this Convention.”157 Article 310 clarifies that rule:

Article 309 does not preclude a State . . . from making declarations . . . with a view . . . to the harmonization of its laws and regulations with the provisions of this Convention, provided that such declarations or statements do not purport to exclude or to modify the legal effect of the provisions of this Convention in their application to that State.158

Because Russia’s declaration under Article 298 did not accord with Article 297, the Netherlands argued, it could not be the case that it shielded Russia from the binding resolution of disputes without violating Articles 309 and 310.159 ITLOS agreed and notified Russia that it did, in fact, have jurisdiction.160

Russia remained obstinate, however. Relying on several ICJ precedents, ITLOS held that “the absence of a party . . . does not constitute a bar to the proceedings.”161 Although ITLOS attempted to take into account Russia’s interest as best it could, it ruled for the Netherlands and ordered the immediate release of the vessel and non-Russian members of its crew in returning for a €3.6 million security bond, pending arbitration.162 Russia refused to comply with the order, although it granted the crew amnesty within a month, released them, and finally released the ship several months later.163

The Netherlands took the case to the PCA the following year to secure a declaration that Russia’s conduct had been a violation of international law, as well as an apology and monetary damages.164 Again, despite ITLOS’s finding of jurisdiction, Russia refused to participate.165 The PCA produced a detailed ruling on the merits of the case, finding unanimously that Russia had violated the Convention and ordering it to return all property confiscated aboard Arctic Sunrise.166 It also ordered damages for harm done to the vessel, although the calculation of damages remains ongoing at the time of writing.167

Taken alone, the Arctic Sunrise cases under Part XV might have been an anomaly among a string of otherwise successful dispute resolutions by the various available forums. The underlying incident was a relatively minor occurrence in comparison with other disputes between the Russian Federation and the West in 2013.168 The case became a turning point in great power approaches to binding dispute resolution, however, when the People’s Republic of China adopted Russia’s theory of Part XV jurisdiction in a high profile case at the center of a major controversy in East Asia.169

B. The People’s Republic of China

The People’s Republic of China was also an original signatory to the Convention in 1982, ratifying the agreement in 1996.170 At the time of ratification, China added a number of qualifications to its participation in the Convention.171 They included an affirmation of “sovereign rights and jurisdiction” over its EEZ, a commitment to resolve border disputes through bilateral negotiations, and a reaffirmation of sovereignty over a number of outlying islands.172 In 2006, China added a remedial declaration under Article 298 to limit its participation in the dispute resolution scheme: “[China] does not accept any of the procedures provided for in Section 2 of Part XV of the Convention with respect to all the categories of disputes referred to in paragraph 1 (a) (b) and (c) of Article 298 of the Convention.”173 This reservation, nearly identical to Russia’s, 174 would play an important role in a future dispute.

1. China followed Russia’s lead in The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of the Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China).

China avoided dispute resolution under UNCLOS for nearly two decades. However, in the same year that Russia refused to participate in Arctic Sunrise, China adopted Russia’s approach and successfully undercut the dispute resolution system. The Philippines brought a case for arbitration to the PCA against China in early 2013.175 The dispute was the most ambitious challenge for Part XV to date, and so it was closely watched by powers around the world and had the potential to reset power dynamics in East Asia at just the point when China was becoming more assertive militarily.176 The Philippines’s move thus represented a critical opportunity for the international legal system to resolve a simmering dispute that experts identified as the “cauldron” in which tensions might boil over into a third World War.177 By any conceivable measure, UNCLOS’s dispute resolution system failed to mitigate that possibility.

The Philippines’s complaint, which encompassed over a dozen legal issues, focused on four broad claims. First, the Philippines challenged China’s claim to sovereignty over the entirety of the South China Sea (the so-called “Nine Dash Line”) under UNCLOS.178 Second, it asked the court to determine whether any land features claimed by China were entitled to their own territorial seas and EEZs.179 Third, it sought a declaratory judgment on the illegality of Chinese actions, including interference with the Philippines’s use of resources in its own EEZ and the infliction of harm on the maritime environment through construction projects.180 Finally, it asked the court to declare that China had aggravated the dispute through a number of questionable tactics.181 The intricacies of the legal issues at stake are of less importance to this Comment than the jurisdictional questions and have been covered at length elsewhere.182 The key consideration for this discussion was in China’s response: “the South China Sea arbitration is null and void, and has no binding effect on China . . . The Philippines’s attempt to negate China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea through arbitral proceeding [sic] will lead to nothing.”183

Perhaps because of the significance of the case (especially when compared to the rather small stakes involved in Arctic Sunrise), the Chinese government took an aggressive stance on the question of the court’s jurisdiction. In its initial note verbale in February, China expressed the argument it would maintain throughout the course of the proceedings.184 First, the core of the dispute was China’s and the Philippines’s competing claims to sovereignty over the Spratly Islands. Because the Convention assumes the sovereignty of the coastal state when establishing territorial rights, it cannot resolve the fundamental disputes that underlie claims. Second, both sides “agreed to settle the disputes through bilateral negotiation” in the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.185 The Declaration was an agreement between China and the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).186 By unilaterally removing the dispute from bilateral negotiations, China argued, the Philippines had departed from “the right track of settling disputes.”187

After the PCA declined to dismiss the case outright, China published an open position paper laying out its argument in greater detail, which the court adopted in lieu of an official submission.188 In addition to earlier arguments on sovereignty and separate dispute resolution agreements, the paper added an alternative argument that China’s 2006 declaration under Article 298 exempted it from the resolution of disputes over maritime delimitation.189 Because the Philippines’s claim was really about sovereignty over islands, the arbitration was tantamount to “a request for maritime delimitation by the Arbitral Tribunal in disguise.”190

After hearings and submissions from both the Philippines and observer states from ASEAN, the court confirmed its jurisdiction to hear the case. Citing both U.S. v. Nicaragua and Arctic Sunrise, the court first determined that China’s refusal to participate did not impede the course of arbitration.191 Second, it rejected the notion that the dispute over sovereignty of the islands was the only matter to be resolved, and that any collateral decision would necessarily (and illicitly) resolve the larger question that was beyond the scope of the Convention.192 The Philippines had carefully selected the issues in its claim to limit the arbitration to the boundaries of UNCLOS and the court’s jurisdiction.193 Third, the court rejected China’s argument that the parties had a binding agreement to settle disputes bilaterally.194 Finally, the court found that seven of the Philippines’s claims clearly did not fall within the Chinese exemption because they were unrelated to the types of activities articulated in Article 297, Paragraphs 1-3 (as in Arctic Sunrise).195 However, it delayed ruling on jurisdiction over seven other claims until the merits phase of the case in order to allow China to articulate a fuller argument on the question of jurisdiction.196

China responded by following Russia’s lead. Beijing asserted that “not accepting or participating in arbitral proceedings is a right enjoyed by a sovereign State. . . . For such a proceeding that is deliberately provocative, China has neither the obligation nor the necessity to accept or participate in it.”197 It declared that the Philippines, which was “fully aware that it was absolutely not possible that China would accept the compulsory arbitration . . . still decided to abuse the provisions of the UNCLOS by unilaterally initiating and then pushing forward the arbitral proceedings.”198 China also chided “other States, who . . . [supported the Philippines’s submission and] apparently have their ulterior motives.”199

In the following months, China continued to stonewall the court as it reached its decision. In the final award, released in July 2016, the court unanimously endorsed the Philippines’s position.200 China, however, maintained course. In the months since the ruling, it has continued construction of artificial islands in the Spratlys, dissuaded the new administration in Manila from pressing the issue through diplomatic outreach, and increased its resistance to American military presence in the area.201

C. The United States

Unlike Russia and China, the U.S. is not a party to the Convention. Although it signed the document, the Senate has steadfastly refused to ratify UNCLOS in the face of domestic opposition resulting both from economic concerns and worries about ceding legal authority to an international tribunal.202 Even though the U.S. Navy has been a strong proponent of ratification and has assumed the role of the Convention’s primary enforcer, it has failed to convince skeptics in Congress.203 This status puts the United States in an awkward position: among the Permanent Members of the U.N. Security Council, it is the only state that rejects Part XV dispute resolution altogether.204

That rejection stems in part from the aversion to international courts that the United States developed in the 1980s. In 1986, the U.S. refused to participate in legal proceedings over its support for the Contra rebellion against the ruling Sandinista government in Nicaragua under customary international law.205 Although the ICJ held in Nicaragua v. United States that the U.S. had violated Nicaragua’s sovereignty, an American veto in the U.N. Security Council prevented Nicaragua from enforcing the judgment in any meaningful way.206 The experience soured the American public to international courts, later leading the U.S. to reject the Rome Statute and participation in the International Criminal Court in 2002.207

It is important to note that, despite its central role in building the post-war liberal international order, it was the U.S. that first popularized the rejection of international courts and binding agreements including UNCLOS.208 Although other countries did not follow the American approach for several decades, the U.S.’s refusal to participate in the Nicaragua case set a direct precedent for Russia in M/V Arctic Sunrise and China in The South China Sea Arbitration.

D. The Future of Binding Dispute Resolution under UNCLOS

Taken together, the developments in Arctic Sunrise and The South China Sea Arbitration may portend difficulties for Part XV in the future. If China, Russia, and the U.S. all reject the system’s legitimacy when the issues are unfavorable to them, other states will have little incentive to submit to resolution of their disputes if the results do not suit their interests. Although these cases may be isolated instances, they seem to reinforce each other by providing a proven method of stonewalling international tribunals behind Article 298 declarations. Because Russia and China seem to have suffered no consequences for their actions, it will be difficult for ITLOS and the PCA to hold other obstinate parties to task in the future.

In the last few months, Russia has withdrawn its support for the Rome Statute and submission to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court.209 Meanwhile, China seized a U.S. Navy research drone operating just 50 nautical miles off the Filipino coast in the South China Sea, outside its “Nine-Dash Line” claim.210 Both actions demonstrate continued and increased opposition on the part of both countries to international law and the peaceful resolution of disputes. In light of their positions in Arctic Sunrise and The South China Sea Arbitration, this behavior seems to establish a pattern of contempt for international legal authority.

A change in the American position would act as a strong counterweight to the Russian and Chinese approach. By ratifying UNCLOS, the U.S. would lend greater legitimacy to its Navy’s perennial efforts to enforce the agreement against both its allies and its adversaries. Additionally, participation would enable American jurists and legal scholars to join the benches of the various forums that hear Part XV cases and influence the development of international maritime law. The United States could enhance the mechanism’s credibility with smaller powers by using it to resolve one of its minor outstanding disputes with Canada.211 Such a move would have minimal economic or territorial consequences, regardless of the outcome, but have strong symbolic value as an endorsement of international law.

However, the Trump Administration seems unlikely to push the Senate for ratification. Its skeptical approach to international trade agreements and alliances suggests that it would have little enthusiasm for a renewed commitment to international law, especially if the public were to perceive the move as a cession of sovereignty to a foreign body.212 Without a renewed American commitment, smaller States Parties will be more likely to dare to adopt the Russian and Chinese approach. Because Part XV has no capable enforcement mechanism, it is likely to fall into disuse for all but the most routine law enforcement cases.

V. Conclusion

This Comment has shown that UNCLOS Part XV has facilitated the resolution of a considerable number of maritime disputes through its relatively complex mechanisms for choice of forum. In the areas of law enforcement and border disputes, it has contributed to a substantive development of international law in its two decades of existence. While some of the design features do not operate in the ways in which their framers intended, Part XV provides useful forums to resolve lingering disputes through a peaceful process.

However, the last few years have seen the emergence of a plot twist: a worrying trend of refusal to participate in that process by great powers. As Russia and then China adopted the American approach to international courts, they undercut the system’s effectiveness and denied justice to their smaller, less powerful neighbors. China’s aggressive campaign to co-opt a new political administration in the Philippines, combined with its continued military activities in the disputed area, is particularly damaging to the practice of binding dispute resolution among nations. With three of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council opposed to jurisdiction of UNCLOS tribunals, smaller states have little incentive to abide by their international commitments. Although the U.S. signaled a willingness to change its approach in recent years, the inauguration of a new administration seems likely to adopt the skepticism toward international courts of administrations dating back to the mid-1980s. While the system will likely continue to function in the short-term, the next contentious case may spell its end.

VI. Appendix

[[{"fid":"551","view_mode":"full","fields":{"format":"full","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_photo_credit[und][0][value]":""},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"4":{"format":"full","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_photo_credit[und][0][value]":""}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-full","data-delta":"4"}}]]

- 1See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 [hereinafter UNCLOS].

- 2See Section II, infra.

- 3See Donald R. Rothwell, Building on the Strengths and Addressing Challenges: The Role of the Law of the Sea Institutions, 35 Ocean Dev. & Int’l L. 131, 131–32 (2004) (“The Convention remains a shining example of international cooperation, diplomacy, and the role of international law in the regulation of international affairs and is considered to be one of the most complex and ultimately successful international diplomatic negotiations that took place in the 20th century.”).

- 4See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 279–99.

- 5The South China Sea Arbitration (Phil. v. China), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2013-19, Award of July 12, 2016.

- 6See Section II, infra.

- 7See generally Rothwell, supra note 3; Sicco Rah & Tilo Wallrabenstein, The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and Its Future, 21 Ocean Y.B. 41 (2007); Rosemary Rayfuse, The Future of Compulsory Dispute Settlement Under the Law of the Sea Convention, 36 Victoria U. Wellington L. Rev. 683 (2005); Helmut Tuerk, The Contribution of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to International Law, 26 Penn St. Int’l L. Rev. 289 (2007). Tuerk served as an ITLOS judge, and his work cataloguing the case law through 2007 remains the best piece on this subject. This Comment will repeat portions of his analysis and attempt to update the law as it has developed in the intervening decade.

- 8See, for example, Steven Groves, The Law of the Sea: Costs of U.S. Accession to UNCLOS—Hearing Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, The Heritage Found. (June 14, 2012), (https://perma.cc/48ZE-6C6Q); see also The United Nations Law of the Sea Treaty Information Center, Nat’l Ctr. for Pub. Pol’y Res., (https://perma.cc/839G-X57J) (last visited Mar. 19, 2017).

- 9China ratified UNCLOS on June 7, 1996; Russia ratified on Mar. 12, 1997. See Chronological Lists of Ratifications of, Accessions and Successions to the Convention and the Related Agreements, U.N. Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (2017), (https://perma.cc/2UCC-YYNJ).

- 10See Section IV, infra.

- 11See J. Inst. 2.1.2. (J.B. Moyle trans., 1911).

- 12Id.

- 13Richard A. Epstein, What is So Special About Intangible Property?: The Case for Intelligent Carryovers, in Competition Policy and Patent Law Under Uncertainty: Regulating Innovation 45 (G. Manne & J. Robert Wright eds., 2011).

- 14Id. at 45–46.

- 15Id. at 45–46 & n. 10.

- 16Hugo Grotius, Mare Liberum (2012).

- 17Id. at 12–15 (“By the Law of Nations navigation is free to all persons whatsoever.”).

- 18Id. at 64.

- 19John Selden, Mare Clausum seu de Domino Maris (Andrew Kembe & Edward Thomas trans., 1663).

- 20Id. at xii.

- 21Id.

- 22See Clive Schofield, Parting the Waves: Claims to Maritime Jurisdiction and the Division of Ocean Space, 1 Penn. St. J.L. & Int’l Aff. 40, 41 (2012) (“For a long period, the demand for freedom of the seas in the interests of ensuring global trade prevailed, with the broad consensus being that coastal State rights should be restricted to a narrow coastal belt of territorial waters.”).

- 23See id. at 41–42. But see generally Wyndham L. Walker, Territorial Waters: The Cannon Shot Rule, 22 Brit. Y.B. Int’l L. 210 (1945) (questioning whether the customary rule was originally associated with cannon range and suggesting alternative theories).

- 24See Schofield, supra note 22, at 42 (articulating the evolution of “creeping coastal state jurisdiction”).

- 25Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Points (1918), Our Documents (Jan. 8, 1918), (https://perma.cc/LUB9-W47M).

- 26See Schofield, supra note 22, at 42 (“While efforts were made towards the codification of the international law of the sea . . . little progress had been achieved by the mid-Twentieth Century. Substantial changes, however, were afoot with more and more States advancing expansive maritime jurisdictional claims—a phenomenon generally termed ‘creeping coastal State jurisdiction.’”).

- 27For a more detailed overview of the modern history of international maritime law and the various U.N. Conventions, see id. at 42–48.

- 28See id. UNCLOS I produced four separate documents: Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, Apr. 4, 1958, 516 U.N.T.S. 205; Convention on the High Seas, Apr. 29, 1958, 450 U.N.T.S. 11; Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas, Apr. 29, 1958, 559 U.N.T.S. 285; Convention on the Continental Shelf, Apr. 29, 1958, 499 U.N.T.S. 311.

- 29Second United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Final Act, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.19/L.15 (1960).

- 30See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 3.

- 31Id. at art. 33.

- 32See id. at art. 56.

- 33Id.

- 34Id.

- 35See Schofield, supra note 22, at 46 (“Consequently, the drafting of [UNCLOS] and widespread claiming of 200 [nautical mile] EEZs represents a profound reallocation of resource rights from international to national jurisdiction. Realising the opportunities raised by these extended maritime jurisdictional claims, notably protecting and managing marine resources and activities, is, however, undoubtedly a challenging task. This task is made all the harder given the jurisdictional uncertainty caused by undefined maritime boundaries and competing claims to maritime jurisdiction.”).

- 36See generally Robin Churchill, “Compulsory” Dispute Settlement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – How Has It Operated?, PluriCourts Blog (Jun. 9, 2016), (https://perma.cc/D29F-YV89) (describing negotiations over the inclusion of Part XV).

- 37Rayfuse, supra note 7, at 683.

- 38Id.

- 39UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 279. Part XV explicitly supports the U.N. Charter’s goal of encouraging the peaceful resolution of disputes. See U.N. Charter art. 2, ¶ 3 & art. 33, ¶ 1.

- 40See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at arts. 283–84.

- 41See id. at art. 287(1).s

- 42See id. at art. 287(1)(a).

- 43See Section III(B)(1), infra.

- 44See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 287(1)(b).

- 45Statute of the International Court of Justice art. 36, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, 33 U.N.T.S. 993.

- 46See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 287(1)(c), Annex VII.

- 47See Permanent Court of Arbitration, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, (https://perma.cc/M9NT-TME7).

- 48See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 287(1)(d), Annex VIII.

- 49Id., at Annex VIII, art. 1.

- 50See id. at art. 287(1).

- 51See id. at art. 287(3), (5).

- 52See id. at art. 287(4).

- 53See id. at art. 287(7).

- 54See id. at art. 287(1).

- 55Churchill, supra note 36.

- 56See United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS: Settlement of disputes mechanism (2017), (https://perma.cc/4YH7-6BVX) (compiling all such choices of procedure). Scholars have offered a number of potential explanations for the “surprising” low number of declarations, including bureaucratic inertia and domestic distrust of international courts (and preference for default arbitration). See, for example, Churchill, supra note 36 at para. 4.

- 57See Rah & Wallrabenstein, supra note 7, at 44. In other cases, the parties sometimes elect to remove the disputes from UNCLOS Part XV mechanisms altogether and find other solutions. “[E]ven where all the parties to a dispute have accepted the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, they are not obliged to submit the dispute to the Tribunal as per Article 280 UNCLOS. The parties still have the option of settling the dispute by means other than the Tribunal.” Id.

- 58This Comment includes all disputes submitted for resolution, regardless of their outcome. Because the Comment’s aim to is to discern trends in the initial selection of the forum rather than development of substantive law, whether a tribunal eventually decides each case on its merits is outside the scope of our attention.

- 59See supra note 7.

- 60See List of Cases, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, (https://perma.cc/GX6V-FYVV) (last visited Mar. 17, 2017).

- 61See Tuerk, supra note 7, at 292 (“The Convention does not contain any provision conferring advisory jurisdiction on the Tribunal as such, which may, however, on the basis of Article 21 of its Statute give an advisory opinion on a legal question if this is provided for by an international agreement related to the purposes of the Convention conferring jurisdiction on it.”). For information on the advisory opinions issued to date, see Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with respect to Activities in the Area, Case No. 17, Advisory Opinion, Feb. 1, 2011, 2011 ITLOS Rep. 10, 16–18, and Request for An Advisory Opinion Submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC), Case No. 21, Advisory Opinion, April 2, 2015, 2015 ITLOS Rep. ___, 20–21, available at (https://perma.cc/3ZB8-P4M9).

- 62See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 290(5).

- 63Churchill, supra note 36. In total, ITLOS has fielded seven cases involving a request for provisional measures. Of the six that were decided (one remains pending before the Tribunal), only Arctic Sunrise was fully arbitrated. See Section IV(A)(2), infra.

- 64See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 292(1).

- 65For commentary on why no further cases had arisen by that time, see Churchill, supra note 36 (“The reason why there have been no applications for almost ten years may be because detaining and flag States have found helpful and acted in accordance with the criteria to be applied in setting a bond that the ITLOS has elaborated in its case law. However, those criteria have been criticised in the academic literature for not showing how the size of bonds actually set by the ITLOS were derived therefrom, with the ITLOS being accused of simply plucking a figure from thin air.”). Cf. M/V Norstar (Panama v. Italy), Case No. 25, Order 2016/1, Feb. 3, 2016, 2016 ITLOS Rep. ___ (being the first case to arise under art. 292 in a decade).

- 66See Proceedings Before the Tribunal, International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, at sec. (i), (https://perma.cc/7UYV-AGQB) (last visited Mar. 17, 2017). Cf. Schedule of Fees and Costs, Permanent Court of Arbitration, (https://perma.cc/3EYM-ZHHE) (last visited Mar. 17, 2017).

- 67See Contentious Cases, International Court of Justice, (https://perma.cc/RWY6-STBT) (last visited Mar. 17, 2017).

- 68See Rah & Wallrabenstein, supra note 7, at 44–45 (“The ICJ has unlimited competence with respect to disputes between States, provided that the States have accepted its jurisdiction.”).

- 69See Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicar. v. Colom.), Judgment, 2012 I.C.J. Rep. 624, ¶ 42 (Nov. 19) (“The Court notes that Colombia is not a State party to UNCLOS and that, therefore, the law applicable in the case is customary international law. The Court considers that the definition of the continental shelf set out in Article 76, paragraph 1, of UNCLOS forms part of customary international law.”); see also Schofield, supra note 22, at 49 (describing ICJ’s application of UNCLOS art. 15 as customary international law).

- 70See Section III(A), supra. The thirteenth case, The Southern Bluefin Tuna Case, was referred to the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and subsequently dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. Because nearly every other Annex VII case has been adjudicated by the PCA, this Comment will focus solely on the PCA’s role as the primary forum for arbitration. See generally Southern Bluefin Tuna Case (Austl. & N.Z. v. Japan), Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of Aug. 4, 2000, Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea.

- 71See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 287, para. 1.

- 72See Section III(C), infra.

- 73See Rah & Wallrabenstein, supra note 7, at n.6 and accompanying text (“There have been no instances of disputes being referred to arbitration in accordance with Annex VIII so far. Given that only eight parties to the Convention have selected Annex VIII arbitration as one of their preferred procedures for the time being, the chances of a dispute being referred to Annex VIII arbitration are currently rather small.”); see also Churchill, supra note 36 (“This is probably because of the small numbers of States selecting these fora as their preferred means of settlement and the fact that the inclusion of Annex VIII arbitration in UNCLOS was a concession to the then Soviet bloc.”).

- 74See UNCLOS, supra note 1, at art. 292(1).

- 75See, for example, M/V Norstar, supra note 65.

- 76Compare Dispute Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary Between Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in the Atlantic Ocean (Ghana v. Côte d’Ivoire), Case No. 23, Order 2016/7, Dec. 15, 2016, 2016 ITLOS Rep. 122 (selecting ITLOS) with The Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration (Bangl. v. India), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2010-16, Award of Jul. 7, 2014 (selecting the PCA).

- 77See Section III(B)(1), supra. Issuance of provisional measures by ITLOS often drives the parties to settlement before their case is arbitrated on the merits. See, for example, Case Concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and Around the Straits of Johor (Malay. v. Sing.), Case No. 12, Order of Oct. 8, 2003, 2003 ITLOS Rep. 10 (ITLOS); Land Reclamation by Singapore in and Around the Straits of Johor (Malay. v. Sing.), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2004-05, Award on Agreed Terms, Sep. 1, 2005.

- 78See John E. Noyes, Law of the Sea Dispute Settlement: Past, Present, and Future, 5 ILSA J. Int’l & Comp. L. 301, 302 (1999).

- 79See The “M/V Saiga” Case (St. Vincent v. Guinea), Case No. 1, Judgment, Dec. 4, 1997, 1997 ITLOS Rep. 16 ¶ 82 (“In the view of the Tribunal, the criterion of reasonableness encompasses the amount, the nature and the form of the bond or financial security. The overall balance of the amount, form and nature of the bond or financial security must be reasonable.”).

- 80See “The Camouco” Case (Pan. v. Fr.), Case No. 5, Judgment, Feb. 7, 2000, 2000 ITLOS Rep. 10 ¶¶ 66–67 (noting that relevant factors include “the gravity of the alleged offences, the penalties imposed or imposable under the laws of the detaining State, the value of the detained vessel and of the cargo seized, the amount of the bond imposed by the detaining State and its form.”).

- 81See M/V Norstar, supra note 65.

- 82See Noyes, supra note 78, at 302.

- 83See The “ARA Libertad” Case (Arg. v. Ghana), Case No. 20, Order, Dec. 15, 2012, 2012 ITLOS Rep. 332.

- 84See The “Arctic Sunrise” Case (Neth. v. Rus.), Case No. 22, Order, Nov. 22, 2013, 2013 ITLOS Rep. 230; see also Section IV(A)(2), infra.

- 85See The ARA Libertad Arbitration, Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2013-11, Termination Order, Nov. 11, 2013.

- 86See The Arctic Sunrise Arbitration (Neth. v. Rus.), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2014-02, Award, Aug. 14, 2015; see also Section IV(A)(2), infra.

- 87See Duzgit Integrity (Malta v. São Tomé and Príncipe), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2014-07, Award, Sep. 5, 2016.

- 88See, for example, Maritime Delimitation in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean (Costa Rica v. Nicar.) and Land Boundary in the Northern Part of Isla Portillos, Order, 2017 I.C.J. Nos. 157 & 165, ¶¶ 16-17 (Feb. 2, 2017), available at (https://perma.cc/4RPP-KJ2Q) (joining the two cases under Art. 47 of the Rules of the Court in order “to address simultaneously the totality of the various interrelated and contested issues raised by the Parties, including any questions of fact or law that are common to the disputes presented”). ITLOS has no such ability to consider issues that do not arise under UNCLOS. The ICJ’s application of other sources of law to maritime disputes dates back to its founding after the Second World War. See The Fisheries Case (U.K. v. Nor.), Judgment, 1951 I.C.J. Rep. 116 (Dec. 18, 1951).

- 89See Schofield, supra note 22, at 48–54.

- 90See Nicar. v. Colom., supra note 69.

- 91See Barb. v. Trin. & Tobago, Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2004-02, Award, Apr. 11, 2006.

- 92See Guy. v. Suriname, Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2004-04, Award, Sep. 17, 2007.

- 93See Bang. v. India, supra note 76.

- 94See Dispute Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary Between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal (Bang. v. Myan.), Case No. 16, Judgment, Mar. 14, 2012, 2012 ITLOS Rep. 4. Bangladesh is the only state that has opted to bring similar disputes to different forums under UNCLOS (the PCA and ITLOS). See Bang. v. India, supra note 76. The decision cannot be explained by Article 287 choice of procedure selections; Bangladesh has opted for ITLOS for specific matters, while both India and Myanmar failed to submit selections and therefore default to Annex VII arbitration.

- 95See The Southern Bluefin Tuna Cases (N.Z. v. Japan; Austl. v. Japan), Cases No. 3-4, Order, Aug. 27, 1999, available at (https://perma.cc/H92X-ML5E).

- 96See The Southern Bluefin Tuna Cases, supra note 70.

- 97See The MOX Plant Case (Ir. v. U.K.), Case No. 10, Order, Dec. 3, 2001, 2001 ITLOS Rep. 95.

- 98See The MOX Plant Case (Ir. v. U.K.), Perm. Ct. Arb. Case No. 2002-01, Order No. 6, Jun. 6, 2008.

- 99See Malay. v. Sing., supra note 77.

- 100See Chagos Marine Protected Area (Mauritius v. U.K.), Case No. 2011-03, Award of Mar. 18, 2015.

- 101See id. at ¶¶ 5–13.

- 102See id. at ¶ 547.

- 103Supra note 5.