Cooperative Federalism and Patent Legislation: A Study Comparing China and the United States

How should patent legislative power be allocated between central and local governments in order to construct a patent system conducive to promoting innovation? A comparative analysis of the models of the U.S. and China sheds light on this question. The early American states established their patent systems before the formation of the federal system, but the U.S. Constitution arrogated patent legislative power to the federal government, ending the era of decentralized patent systems. This centralized structure ensures uniformity in rules but might hinder the system’s adaptability and ability to experiment. In contrast, as China’s patent system evolved, its patent legislative power spread from the central to the local governments. This shift led to the coexistence of dual-level patent legislative structure. Currently, twenty-nine out of thirty-one province-level authorities (93.5%) and twenty-one out of 323 city-level authorities with local legislative power (6.5%) have established local patent laws. China’s patent system is not entirely decentralized but rather, semi-decentralized, as the locales not only implement their local patent laws but also must enforce the central government’s national patent laws. China’s semi-decentralized patent legislation model embodies significant features of cooperative federalism, where the central and local governments share the national power to handle affairs and collaborate to address issues. Yet, the central government maintains a dominant position in this cooperative relationship, as a consequence of China’s unitary state structure. Compared to the current centralized patent legislation model in the U.S., China’s semi-decentralized patent legislation model has the advantage of making statutory law more adaptable to local specificities and promoting local competition and institutional innovation. However, it also faces challenges, such as increased costs due to inconsistency; efficiency decline stemming from rent-seeking behaviors; and the risk that local protectionism will create anti-competitive effects.

I. Introduction

The patent system is a pivotal component of the innovation infrastructure in contemporary industrialized nations. By granting inventors exclusive rights to their inventions for a set period, it encourages investment in innovation and facilitates the disclosure of novel technological knowledge.1 The allocation of patent legislative power between central and local governments can shape the development of this system, either bolstering or undermining its ability to foster innovation. But what is the optimal way to distribute this power? An exploration of the patent legislative models in China and the United States can shed light on this intricate question, helping to elucidate the interplay between law and innovation.

Although it began with a decentralized patent system, where states created their own patent schemes in the absence of a national patent law,2 the U.S. currently centralizes patent legislative power, as do many of the world’s major industrialized economies, such as the United Kingdom,3 Japan,4 and Germany.5 In the U.S., Congress established a federal statutory framework that governs patents across the nation.6 The roots of this system appear in the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 grants Congress the power to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”7 This provision vests the power of patent legislation in Congress. As Edward Walterscheid, the preeminent historian of this constitutional clause and American patent law, noted, “the enactment of federal patent and copyright laws in 1790 was largely viewed as removing the need for state patents and copyrights, because the advantages of uniformity and broader protection inherent in the federal system were obvious to almost everyone.”8 States retained no legislative power; patent law became purely federal.9 For over two hundred years, states have not been authorized to issue their own patents, and this remains the case today.10

A uniform patent law that offers protection across states is a benefit of centralized legislation under a federal system. However, for the achievement of cross-state patent protection within a federal system, complete centralization of legislative power doesn’t appear to be necessary. A middle ground exists between the full centralization and full decentralization of legislative power, where the central government and local governments can co-exist in patent lawmaking.11 In this intermediate state, a central government can offer extensive patent protection through legislation while local governments can refine the patent system in cooperation with the central government. However, the current U.S. system does not offer state governments any avenues by which to participate in the making of patent law. This approach maintains legal uniformity and avoids rule diversity.12 But, as Roger Ford pointed out, uniformity in patent law does not guarantee an optimal level of patent protection.13 Centralizing patent legislative power at the federal level keeps states from enacting patent laws that reflect their specific conditions and the needs of their specific industries and innovator communities.14 It also means that they cannot experiment with different laws and approaches related to patent issues.15 Thus, the conclusion that the benefits of maintaining uniformity in patent rules outweigh the cooperation between state and federal governments in constructing the patent system is not a given.

Collaboration between central and local governments in institution-building is not a novel concept. In constitutional law, one characteristic of cooperative federalism, which originated in the New Deal era in the U.S.,16 is the sharing of regulatory authority between the federal government and the states, allowing states to regulate within a framework that federal law delineates.17 This model fosters problem-solving cooperation between different levels of government,18 providing a flexible framework that adjusts to changing circumstances.19 It stands in contrast to the concept of dual federalism, which imposes a rigid division of powers,20 defining a distinct regulatory domain which it assigns to one level of government and fortifies against encroachment from others,21 thereby creating “tension rather than collaboration” between federal and state governments.22 It also differs from preemptive federalism, in which a unitary federal system overrides all state authority “instead of leaving room for state regulation.”23

Environmental legislation in the U.S. exemplifies cooperative federalism. Federal agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency establish broad environmental standards and policies, while states fine-tune their implementation and enforcement according to local conditions; the Clean Air Act exemplifies this system.24 Environmental issues, such as air emissions, necessitate the intervention of the central government due to their cross-boundary nature, which often extends beyond individual jurisdictions.25 However, the participation of local governments is equally vital, as they are best positioned to adjust centrally crafted laws to meet local needs and conditions.26 A cooperative federalism model that sets broad federal guidelines while permitting state-level variations allows states to offer tailored solutions and to engage in state-level institutional experimentation, thereby fostering institutional innovation.27

Like environmental concerns, issues of innovation have both local and cross-border ramifications. A national patent system under the central government’s auspices is valuable because the benefits generated by new inventions can diffuse across state boundaries and potentially cover the entire society. It can be challenging for a state’s powers to enable the inventor to convert these cross-border benefits into revenues to stimulate their innovation.28 Establishing separate patent systems in each state, requiring inventors to secure patent rights individually in each, could result in substantial costs and be socially wasteful.29 Conversely, a cross-border national patent system could mitigate this resource wastage. Yet, the localized aspects of innovation should not be overlooked. Innovation is inherently specific to location and sector,30 so introducing a cooperative federalism model, which allows local governments to adjust and refine the patent law that the central government has enacted, can facilitate a more nuanced and effective system to encourage innovation.

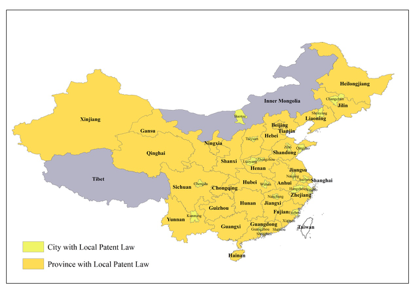

In contrast to the U.S., China has developed a patent regime that embodies a cooperative approach between central and local governments. While Western scholars have paid attention to China’s patent system for quite some time, they have only focused on the national patent laws of the central authority.31 In doing so, they have largely overlooked the significant shift toward the decentralization of China’s patent system over the past three decades.32 On October 9, 1996, the Standing Committee of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Congress enacted and implemented the Guangdong Province Patent Protection Regulations. Since then, an increasing number of local governments in China have formulated their own patent laws. Through a comprehensive survey of China’s local patent laws, this Article has found that as of January 16, 2023, twenty-nine of the thirty-one (93.5%) province-level authorities had passed one or more patent laws applicable to their administrative region.33 Of the 323 city-level authorities with local legislative power, twenty-one (6.5%) have enacted patent laws. Cities that have not done so are still bound by the patent laws of their provinces. To be clear, China’s patent system is not fully decentralized but rather, it is semi-decentralized, as the central government’s national patent laws remain applicable at the local level.

The semi-decentralized patent legislation model in China presents important features of cooperative federalism, where local governments collaborate with the central government regarding patent legislation. Despite the distinctive nature of China’s patent legislation model, which diverges from the predominantly centralized patent regimes of the U.S. and many other industrialized countries, existing literature has not sufficiently explored the specifics and implications of this model. Consequently, much of its impact remains largely unexplored. An analysis of China’s semi-decentralized patent legislation model can not only help policymakers and scholars rethink whether the prevailing centralized patent system is the optimal arrangement, but it can also provide a specific case study about the cooperation between central and local governments in this area.

To unpack China’s semi-decentralized patent legislation model, this Article examines the distribution of China’s patent legislative power within its unitary state structure, systematically analyzes China’s local patent laws, and evaluates their merits and challenges. In order to reveal the characteristics of the semi-decentralized patent legislation model more comprehensively, this Article adopts a comparative analysis approach when investigating the distribution of legislative power and evaluating its merits and challenges, specifically contrasting it with the patent legislation model of the United States.

The Article suggests that the Chinese central government’s distribution of patent legislative powers to provincial and municipal entities has cultivated a layered patent system. In this structure, national and local patent laws coexist. Within this cooperative relationship, the central government maintains a dominant position as a result of China’s unitary state structure. Below that, three factors drive local patent legislation: directives from the central government to bolster intellectual property protection; competition among local governments following centrally determined evaluation schemes; and the central government’s emphasis on rule-of-law governance aimed at enhancing the adaptability of laws to specific socio-economic conditions. The involvement of local governments in shaping the patent system enhances patent laws’ adaptability to local specifics and fosters institutional innovation. However, this model also grapples with challenges, including the additional costs stemming from inconsistencies in laws, a decline in efficiency because of rent-seeking behaviors, and the risk of anti-competitive effects spurred by local protectionism.

Following the introductory section, Section II compares the models of patent legislation in the U.S. and China, that is, decentralized and centralized legislation within a federal structure, and semi-decentralized legislation within a unitary structure. The Article underlines that the former is a non-cooperative model, where central and local governments do not work together in the institution-building of the patent system through legislation, while the latter is a cooperative model, in which the local governments participate in patent legislation with the central. Section III illustrates how local governments in China enact patent laws under the promotion of the central government, identifying three critical factors that propel local patent legislation. Section IV, a survey of Chinese local patent laws, reveals how city and provincial governments adapt the patent system to local specificities. Section IV also contrasts five Chinese provincial administrative regions in terms of their patent legislation, showcasing how they adjust the level of patent protection to align with local conditions amid regional competition. Section V analyzes the merits of China’s semi-decentralized patent legislation model and the challenges it faces by comparing it with the patent legislation model in the U.S. A conclusion follows.

II. The Patent Legislation Models in the U.S. and China

A. Non-Cooperative Models in the U.S.

The federal system in the U.S. emerged from the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, at which the delegates formulated a constitution that would address the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation34 and strike a balance between a strong central government and states’ autonomy,35 allocating legislative powers between federal and state governments. This framework grants the U.S. Congress the power to enact centralized legislation regarding matters of national importance.36 While it is true that federal law has progressively extended into areas once under state jurisdiction, this does not mean an outright usurpation of state control.37 Rather, in many instances, Congress chooses not to exercise its constitutionally-granted federal powers, indirectly allowing states a degree of governance flexibility.38 However, tracing the evolutionary history of the patent system, it appears that Congress has fully assumed patent legislative power from the states, leaving little flexibility for state regulation.

During the period between independence and the ratification of the Constitution, individual American states and colonies encouraged inventors and entrepreneurs, granting them exclusive rights to innovations of local benefit.39 These grants differed from modern U.S. patents in that they did not require universal novelty or original inventorship; instead, they focused on establishing beneficial technology within the state.40 During this period, the states operated their patent systems independently. No cooperation existed with a central governing body akin to the current federal government.

The expansion of interstate commerce and improvements in transportation rendered state patents less viable. Steam-powered transportation facilitated trade between states, posing challenges in enforcing patents even within a single jurisdiction.41 Inventors increasingly realized the necessity for a national patent system that would create broader protection and maximize profits across multiple states.42 They advocated the creation of a unified system that would ensure consistent rulings and address issues of priority and infringement.43 The Framers of the Constitution acknowledged the limitations of individual state provisions. James Madison wrote in Federalist Paper No. 43 that “[t]he States cannot separately make effectual provisions for either of the [patent or copyright] cases.”44 Without significant debate, they added the Intellectual Property Clause to the Constitution, affirming the need for a centralized patent system.45

So, while legislative powers in the U.S. are divided between the federal and state governments, when it comes to patents, only the federal government has authority. This power stems from Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution, which leaves the states with no role in patent legislation. While the colonies had patent-like rights before the Constitution’s ratification, and a few states continued this practice in the early years of the U.S., the granting of state patents gradually ceased, with New York awarding the last one in 1798.46 While studies indicate that the Framers permitted states to maintain their own autonomous power to grant patents, leading to ongoing debates about the scope of this authority and its interaction with federal patent law,47 courts generally recognized that only Congress has the power to enact patent-related legislation. In the case of Bonito Boats, Inc. v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc.,48 the U.S. Supreme Court firmly established that states are prohibited from granting patents or similar rights due to preemption by the Supremacy Clause. This restriction ensures that state-level competition will not undermine inventors’ decisions to pursue U.S. patents and preserves Congress’s exclusive authority to define patentability requirements and terms.49 In the case of Hunter Douglas, Inc. v. Harmonic Design, Inc., the Federal Circuit affirmed that the Congress-enacted Patent Act “occupies the field of patent law.”50

This centralizing legislative power at the federal level has precluded state governments from collaborating with the federal government in the construction of patent systems via legislation. Yet, as Roger Allan Ford underscores, many states have made endeavors to integrate themselves into the patent landscape.51 Their efforts, however, have been largely restricted to modulating patent litigation procedures due to the concentration of patent legislative authority at the federal level.52 My analysis suggests that the rationale for concentrating patent legislation authority at the federal level is insufficient because it does not take into account the intermediate scenario in which states do not separately enact patent laws but do cooperate with the federal government. Granted, state legislative involvement might introduce inconsistencies in the rules. However, whether the negative impact of such inconsistencies outweighs the positive effects of cooperation between federal and state governments warrants further examination. The need for cross-state protection of patents justifies granting the federal government the power to legislate patents, but it does not suffice as a reason to remove all legislative power from state governments.

B. A Cooperative Model in China

Unlike the federal system in the United States, the unitary system in China emerged over millennia, shaped by the country’s long history of imperial rule and consolidation of power,53 culminating in the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949.54 This unitary Chinese system amalgamates power in the central government.55 The principle of democratic centralism has been foundational to China’s political system; all of the constitutions of the PRC emphasize the leading role of the central government.56 Local governments retain the limited authority to implement and adapt centrally mandated policies within their jurisdictions.57 The power dynamic between the central government and local governments under China’s unitary system achieves a balance between national unity and local responsibility by emphasizing central leadership while allowing local governments to exercise power within a certain range.58

Since the establishment of the PRC, legislative powers in China have primarily resided within the central government, affecting patents, as well as many other fields. The 1954 Constitution formalized this highly centralized legislative system, with the National People’s Congress (NPC) as the sole organ for exercising legislative power.59 To enhance efficiency, in 1955, the NPC delegated some of that law-making power to its Standing Committee.60 Under the current Constitution and Legislation Law, the NPC enacts and amends fundamental laws, while the Standing Committee legislates other matters,61 such as the three primary national Intellectual Property laws—the Trademark Law, the Copyright Law, and the Patent Law. The State Council and its departments also have legislative authority, but the laws that the NPC and its Standing Committee enact supersede it.62 The State Council received its legislative power in 1982,63 under Article 89 (1) of the Chinese Constitution.64

Local authorities in China only began acquiring legislative power in 1979,65 with the Constitution formalizing this in 1982.66 It wasn’t until 1986 that the Organic Law of Localities delegated power to enact local laws at the city level to the people’s congresses and standing committees of forty-nine cities.67 The Legislation Law, which the NPC adopted in 2000 and amended in 2015, expanded this delegation to 289 cities.68

One area that exemplifies the decentralization of legislation in China is the field of patents. Beginning with Guangdong’s first local patent law in 1996,69 localities have progressively enacted patent legislation. This decentralization is manifested by the central government actively encouraging local legislative bodies to establish local intellectual property laws, including patent laws and laws related to patents. The central government generally does this by providing policy guidance using official documents,70 policy directives,71 and speeches by top leaders.72 This guidance helps to align local legislation with the overall objectives of the central government. In the field of patent law, the central government’s two most important guidelines are the 2008 National Intellectual Property Strategy Outline, and the 2021 Outline for the Construction of a Strong Intellectual Property State (2021–2035).73 The State Council promulgates these guidelines to the lower levels of government. In the former Outline, the central government requires local governments to accelerate the building of the intellectual property legal system to adapt to new IP issues in a timely and effective manner.74 The latter requires local governments to make and amend IP laws “promptly” so as to “adapt to the needs of scientific and technological progress and economic and social development.”75

While China’s patent system leans towards decentralization, this contrasts sharply with the period in U.S. history when state patents were operational in the absence of a nationwide patent law. The move towards decentralization in China’s patent system is uniquely underpinned by a unitary structure. In this structure, regional governments enact local patent laws that operate alongside national patent laws. These local patent laws must be consistent with the Constitution and national laws that the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the State Council have promulgated.76 This layered system of coexistence of national and local patent laws forms a “semi-decentralized system.” This system exhibits significant attributes of cooperative federalism as regional governments collaborate with the central government in constructing patent systems through legislation, thereby addressing innovation-related issues. However, this system diverges from the federal system in the U.S. where the power to deal with specific matters is distributed between local and central governments, both being equal in status.77 In China, the central government maintains a dominant position in this cooperative relationship, a stance rooted in its unitary state structure.

III. Cooperative Federalism in China: Central Government Guided Local Patent Legislation

Why do local governments want to engage in the patent legislation that the semi-decentralized patent system in China encourages? An analysis of legislative guidance documents from the central government and legislative preparation documents at the local level offers valuable insights. Overall, the formation of China’s semi-decentralized patent system follows a top-down approach. Local patent legislation acts as a tool for enhancing the patent systems that the central government sets out within a defined blueprint. We can view the process of forming such a semi-decentralized patent system as a nationwide experiment taking place across diverse regions, under the central government’s guidance and supervision.78 Lisa Ouellette describes this as an experimentalist system, representing a third alternative often overlooked in the debate between centralized uniformity and local control.79

One key factor contributing to the development of this semi-decentralized patent system is the central government’s increasing emphasis on the importance and protection of intellectual property. In 2008, China’s State Council promulgated the National Intellectual Property Strategy Outline to strengthen the role of intellectual property in economic, cultural, and social policies. Complementary to this, former Premier Wen Jiabao proposed in the government work report at the Fifth Session of the 10th National People’s Congress that “we should speed up the formulation and implementation of the national intellectual property strategy and earnestly strengthen the protection of intellectual property.”80 Moreover, the Central Economic Work Conference called for the vigorous implementation of an intellectual property strategy that would “gradually spread” from the national level to regional ones.81 In other words, the central government requires local governments to take active steps to enact local intellectual property laws. In 2019, the General Office of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of Intellectual Property, further proposing to “strengthen the protection of intellectual property.”82 In response to this encouragement, local governments have passed laws that provide levels of protection that are higher than those of the national patent law system.83

Building on this foundation, a second driving force is the competition among local governments as they strive to offer ever higher levels of patent protection to secure a competitive edge. By enhancing patent protection, they safeguard the investments of innovators, enticing them to engage in local innovation and thereby stimulating economic growth. This motivates local officials to enhance the economic performance of their jurisdictions, as China’s cadre evaluation system—one of the ways that the central government assesses the performance of local officials—places considerable emphasis on economic indicators.84 Metrics such as GDP growth rate and fiscal revenue contribute significantly to these evaluations.85 The direct link between economic performance and the career prospects of officials gives them an incentive to prioritize economic growth. Recent reforms in China’s official promotion mechanisms have further intensified this patent-related competition among local jurisdictions. Evaluations of local party and government leaders now factor in their accomplishments in innovation-driven development, including improvements in intellectual property laws, the exploration of protection strategies for innovative outcomes in new business models, the refinement of litigation mechanisms, enhanced infringement investigation and enforcement, and the establishment of mechanisms to assist in overseas intellectual property rights protection.86

Competition among localities in terms of economic growth and intellectual property protection drives the decentralization of China’s patent system. Take for instance Guangdong, a developed southeastern coastal province, which aims to “continuously innovate and build a new highland for intellectual property protection.”87 The provincial government believes that this principle will cultivate innovative enterprises with independent intellectual property rights and core competitiveness, boosting the province’s economy.88 Recognizing the intensifying domestic market competition, the neighboring government in Hunan province notes that “enterprises in developed coastal regions are accelerating patent layouts,” leading to imbalances in regional intellectual property development and widening economic and social disparities.89 It believes that formulating its own local patent laws to enhance patent protection is an “urgent need.”90

A third factor contributing to the formation of the semi-decentralized patent system stems from the central government’s active promotion of a rule-of-law-based government. It encourages localities to establish functional, scientifically organized, legally accountable, strictly enforced, open, fair, honest, efficient, and law-abiding administrations.91 This process includes two aspects that are closely related to local patent legislation. First, “strengthening government legislation in key areas” is vital when building a rule-of-law-based government,92 especially in the area of technological innovation.93 Second, “proactively adapting legislation to the needs of reform and economic and social development” is a core requirement.94 As the central government actively promotes itself as a nation with a strong intellectual property framework,95 local governments recognize that the current patent system cannot meet their region’s evolving needs.96 Thus, it is critical that they formulate local patent and intellectual property laws that will improve their local legal and policy systems and allow them to respond to changing economic and social developments.97 The combination of strengthening innovation-related legislation and adapting that legislation to reform and development needs drives local patent legislation, further decentralizing China’s patent system.

At present, China’s local patent systems consist of the laws that the authorities at the province and city levels have enacted. These laws take two forms: specialized patent legislation, which focuses exclusively on patent-related content, and IP legislation, which covers not only patents but also other types of IP, such as copyrights. In this Article, the term “patent legislation” refers to both forms, including stand-alone patent laws and patent-specific sections within broader IP laws. As of January 16, 2023, twenty-nine of the thirty-one (93.5%) province-level authorities had enacted one or more patent laws applicable to their administrative region. Only the province-level authorities of Tibet and Inner Mongolia have not done so. Of the 323 city-level authorities with local legislative power, twenty-one (6.5%) of them have enacted patent laws applicable to their administrative region.98 Although a relatively small percentage of cities have local patent laws, those that do not are still bound by the patent laws of their provinces. A rare case is when there is city-level patent legislation but no province-level patent legislation. Inner Mongolia does not have province-level patent legislation, but Baotou, a city in the province, does have one in place: the Baotou City Patent Promotion and Protection Regulations.99 Cities that have local legislation regarding patents are usually among the most economically developed cities in their province. For example, in 2021, Baotou, with a thriving rare earth industry,100 had the second highest GDP of any city in Inner Mongolia.101 Currently, there is a growing trend toward city-level patent legislation, with city governments either enacting patent laws or incorporating patent-related content into their intellectual property legislation.102

IV. A Survey of the Local Patent Legislation in China

A. Local Patent Legislation to Adapt to Regional Specificities

Increasing the adaptability of the patent system, or more broadly, the intellectual property system, to local economic and social needs is a requirement that the central government imposes on localities. This is evident in the 2008 National Intellectual Property Strategy Outline and the 2021 Outline for the Construction of a Strong Intellectual Property State (2021–2035).103 The State Council has promulgated these guidelines for China’s lower levels of government.104 In the former outline, the central government requires local governments to “accelerate the building of the intellectual property legal system” in order to “adapt to new IP issues in a timely and effective manner.”105 The latter requires local governments to make and amend IP laws and regulations “promptly” so as to “adapt to the needs of scientific and technological progress and economic and social development.”106 In fact, the Legislation Law obligates local authorities to take local specificities into account. Articles 80 and 81 of the Legislation Law require the local people’s congresses and standing committees to legislate in accordance with the “specific circumstances and practical needs.”107

It should not be surprising that the central government emphasizes the adaptability of local patent legislation. Regional economic disparities, variations in industrial structure, cultural differences, and other factors lead to the need for well-tailored patent law that can meet specific local circumstances. In fact, most of China’s local patent laws explicitly state that they were enacted based on local circumstances.108 These circumstances include local industries, local development plans, local traditions and culture, as well as political functions delegated to the locality by the central government.

1. Adaptation to local industries.

Different regions have unique industry clusters, which require patent laws that cater to their specific needs. For example, regions with strong technology and innovation-driven industries might require more stringent patent protection and enforcement mechanisms. As of January 2023, fourteen of the thirty-one province-level authorities had introduced special provisions into their local patent laws to accommodate established and upcoming local industries.109 Ten of the twenty-one city-level authorities (or almost half) have enacted special provisions for local industries.110

The measures that local legislatures introduce through patent laws for local industries are diverse, adopting one approach or a combination of several. Typical financial measures include government-funded support for the industrialization of patented technologies of local industries,111 as well as prizes for patents and the patented products of those industries.112 In terms of acquiring patent rights, local governments grant priority for review,113 or privilege for faster review, to the technologies belonging to the industries that local policies support.114 Patent rights belonging to these industries often receive better protection and enjoy expedited enforcement processes.115

The measures targeting advantageous industries in different regions reflect the patent system’s adaptability to local specificities through local patent laws. A comparison between Beijing and Yunnan’s local patent laws demonstrates this. Beijing’s legislature has incorporated five industries—mobile internet, big data, artificial intelligence, quantum technology, and cutting-edge biotechnology—into the scope of its supported measures,116 reflecting and enhancing the region’s comparative advantage in these areas. Beijing is home to prestigious universities and research institutions that contribute cutting-edge research in these fields.117 The region’s well-developed infrastructure and vibrant innovation ecosystem further support these industries.118 In contrast, Yunnan’s local patent law supports industries such as biology, opto-electronics, high-end equipment manufacturing, new materials, renewable energy, and energy conservation,119 reflecting and enhancing its regional comparative advantage. Yunnan, located in southwest China, has abundant sunlight120 and diverse manufacturing capabilities.121 This province is one of the most biodiverse in China, hosting 51.6% of China's high plant species, 54.8% of its vertebrate species, and 72.5% of the country’s priority protected wild animals, with 15% of these species endemic to the region.122 Rich biodiversity provides a valuable resource base for biotechnology research and development. A semi-decentralized patent legislation model allows local governments to tailor their patent systems in ways that are advantageous to their regions’ industries.

2. Adaptation to local development plans.

To promote innovation, attract foreign investment and technology transfer, and experiment with new legal and policy approaches, China’s central government has established several distinct zones across the country, including Special Economic Zones,123 Economic and Technological Development Zones,124 Independent Innovation Demonstration Zones,125 and Pilot Free Trade Zones.126 These allow local governments to test new laws and policies. Successful implementations can then potentially spread to other regions and stimulate their economic growth and development.127 Local governments often introduce patent law provisions tailored to these zones, enabling patent-related experimentation. Eight administrative regions have incorporated into their patent laws provisions related to Pilot Free Trade Zones,128 generally aiming to enable,129 encourage,130 support,131 or even mandate132 the development of innovative patent-related approaches. Examples include Anhui’s focus on enhancing patent protection effectiveness,133 Hubei’s exploration of integrated patent management and public service systems,134 Jiangsu’s pilot trials to protect patent rights in cross-border e-commerce,135 and Shenzhen’s experimentation with new dispute resolution and enforcement mechanisms.136

3. Adaptation to local traditions and culture.

Local patent legislation aimed at preserving and protecting intangible assets that derive from regional culture and traditions reflect China’s vast and diverse cultural heritage, spanning various regions and ethnic groups. This heritage includes Chinese medicine, traditional knowledge, and the traditional crafts of ethnic minorities.137 Local measures generally focus on providing protection138 to and promoting the utilization of these intangible assets.139 For example, Xinjiang is home to Uygurs and Kazakhs,140 who excel in traditional crafts such as carpet weaving, musical instrument making, horse gear manufacturing, and metalwork.141 Xinjiang’s local patent law encourages innovation in these crafts to generate new techniques, products, and practices.142 In Hainan, the Li and Miao peoples are known for their textile techniques.143 Hainan’s local patent law not only promotes innovation in these traditional crafts but also emphasizes their protection. For those engaged in these crafts, the government provides guidance and counseling on how they can use the intellectual property system for their own protection.144 This focus on preserving and promoting intangible cultural assets showcases the adaptability and importance of local patent legislation in addressing the unique needs and heritage of China’s diverse regions.

4. Adaptation to local political functioning.

Localities, notably Fujian, have used their patent laws to promote the reunification of mainland China and Taiwan. Lying just across the Taiwan Strait, Fujian shares close historical and cultural ties with Taiwan. The province also serves as a key area for cross-strait economic exchange and cooperation. In recent years, China’s central government has implemented preferential policies to encourage Taiwanese businesses and individuals to invest in and move to Fujian, fostering closer economic ties between the two sides. Notable examples are the Measures for Promoting Cross-Strait Economic and Cultural Exchange and Cooperation that the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council and the National Development and Reform Commission introduced in February 2018.145 These measures introduced thirty-one specific policies to improve the treatment of Taiwanese enterprises in the areas of investment and economic cooperation, as well as the conditions for Taiwanese individuals studying, starting businesses, working, and living on the mainland.146 Fujian’s patent law requires local governments above the county level to help patent agencies in Taiwan set up branches in their regions and encourages Taiwanese residents who have obtained mainland patent agent qualifications to intern or practice in local patent agencies.147 Further, legislators in Xiamen, Fujian’s most economically developed city, introduced measures that support private capital and institutions in Taiwan, such as IP fund investment and IP operation.148 These institutions allow entities that implement Taiwanese IP, including patents, in Xiamen to benefit from the city’s incentive policies.149

B. Local Patent Legislation Can Adjust Levels of Patent Protection

China’s innovation economy demonstrates significant regional disparities, with the eastern coastal regions seeing more advantages, even as the central and western regions gradually catch up.150 The eastern coastal areas, including the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, serve as the nation’s innovation powerhouses due to their advanced infrastructure, global market access, and skilled labor forces.151 These regions host high-tech industries such as biotechnology, information technology, and advanced manufacturing, as well as renowned universities and research institutions. Meanwhile, the central and western regions, whose development has lagged historically,152 are now emerging as innovation centers.153 The Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Zone154 and Wuhan155 are gaining prominence due to government incentives and investment. The patent protection measures that these regions have adopted show a certain correlation with the geographical distribution of the innovation economy. Broadly speaking, although different regions exhibit local competition in patent protection, regions with strong innovation economies tend to provide stronger patent protection than do regions with weaker innovation economies.

We can see the practice of local competition through strengthened patent protection in programmatic documents or explanatory materials on patent legislation. The southeastern coastal areas of China, such as Guangdong Province and Shanghai, which have advanced innovation economies, are pioneers in local patent legislation. Guangdong has ranked first in terms of GDP among all provinces in China for thirty-four consecutive years,156 while many have hailed the province’s city of Shenzhen as “China’s Silicon Valley.”157 In the drafting notes for the Guangdong Intellectual Property Protection Regulations, the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee and the Provincial Government emphasize the importance of intellectual property protection and propose the strategic goal of “building a high-standard intellectual property protection highland.”158 In its Shenzhen Intellectual Property Strategy Outline (2006–2010), Shenzhen also outlined its objective of building a strong intellectual property city, aiming to “enhance the core competitiveness of industry and the city.”159

Shanghai, as the central city of the Yangtze River Delta, similarly used its Intellectual Property Strategy Outline (2011–2020) to highlight the importance of strengthening local intellectual property protection, and as a means to achieve the goal of “building an Asia-Pacific Intellectual Property Center.”160 The subsequent Shanghai Intellectual Property Strong City Construction Outline (2021–2035) further emphasized the development direction of building an “international intellectual property protection highland.”161 The use of terms like “highland” and “center” reflects the regional competition to elevate intellectual property protection levels, as they signify the aspiration to create a prominent and leading position in the field of intellectual property protection.

In contrast, while also driven by competition, patent legislation in Central and Western China tends to be responsive to the southeastern coastal regions. For example, the Hunan162 Intellectual Property Office’s legislative notes on Hunan’s local patent law state that due to the accelerated patent layout of enterprises in developed coastal areas, “the imbalance in regional intellectual property development will further widen the gap in economic and social development.”163 Therefore, formulating local patent laws has become an “urgent need” as a way to respond to “domestic competition.”164

Local patent laws, building upon the foundation of China’s national patent system, have a number of ways to strengthen patent protection. One primary approach is to enable innovators to obtain patent rights more easily by establishing government-funded special programs to subsidize patent applications,165 extending support and assistance to individual innovators throughout the application process,166 offering guidance and consultation services to patent applicants,167 and giving priority to patent applications related to locally-recognized key technologies and essential products.168 These measures can alleviate the financial burden on applicants during the application process, streamline that process to increase the likelihood of successful applications, and ensure that inventors are better prepared to submit complete applications, ultimately enhancing their chances of obtaining patent protection.

Another category of measures aimed at improving patent protection levels involves strengthening patent enforcement. To this end, administrative law enforcement departments carry out specialized actions in an effort to investigate and crack down on infringement activities.169 Moreover, administrative departments, such as intellectual property, tourism and culture, public security, and customs can strengthen patent enforcement by pooling their resources.170 Establishing an information-sharing system between these departments171 can enhance the timeliness of enforcement actions. In places like Shanghai and Beijing, intellectual property administrative departments have adopted cutting-edge technologies, including big data, artificial intelligence, and real-time mobile monitoring, to detect infringement activities.172 Use of these technologies enables more accurate and timely identification of potential infringement, allowing law enforcement agencies to respond quickly and effectively. Some regions have established an intellectual property protection assessment mechanism that assesses the performance of responsible authorities and relevant departments in fulfilling their legal duties to protect intellectual property rights.173 This mechanism ensures accountability and encourages continuous improvement in rights enforcement. Furthermore, there are regions that have implemented an incentive system to recognize and reward collectives and individuals who make outstanding contributions in the realm of intellectual property protection.174 Some local intellectual property laws require intellectual property administrative departments to establish legal aid mechanisms and accept applications for enforcement assistance.175 These mechanisms help patent holders who lack resources with which to enforce their rights.

The introduction of local preventive measures is another means to strengthen patent protection. Patent laws in some regions require third parties, such as exhibition organizers, professional market operators, major sports and cultural event organizers, and advertising operators, to check whether the entities entering their premises or participating in their activities might infringe upon others’ patent rights.176 Obligating these third parties to perform due diligence reduces the likelihood of patent infringement occurring in such venues or during such activities and deters potential infringers. In contrast, some local patent laws have implemented intellectual property credit evaluation mechanisms for dishonest behavior.177 When the government carries out administrative activities related to patents—such as approving government investment projects, allowing government procurement and bidding, providing government financial support, and offering awards and recognition—it checks the credit records of the relevant entities. Those with poor histories face negative consequences, such as being banned from undertaking government investment projects, from participating in government procurement, and bidding or being denied access to government financial support and other preferential policies.178 This mechanism creates a deterrent effect by discouraging entities from engaging in patent infringement, so as to avoid the significant disadvantages to obtaining benefits.

Analyzing local patent laws in various provincial-level administrative regions in China, including the southeast coastal area and the central and western districts, offers insights into the competitive landscape of patent protection and regional differences in the effectiveness of patent protection. To maintain regional competitiveness and establish themselves as a “highland” for intellectual property protection, both Guangdong and Shanghai have adopted measures to strengthen patent protection, including making it easier for innovators to obtain patent rights.179 Both jurisdictions use advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence180 and multi-departmental collaborative enforcement mechanisms,181 and provide legal aid to patent rights holders. They also impose obligations on third parties to prevent patent infringement through information review182 and introduce credit evaluation systems.183 Guangdong, unlike Shanghai, incorporates intellectual property protection into administrative personnel assessments.184 In contrast, Shanghai is gradually establishing a unique public interest litigation system in the field of intellectual property, where the procuratorate, rather than the rights holder, combats infringement through judicial proceedings.185 So far, none of the public interest litigation has involved patent enforcement,186 so its impact on patent rights holders is untested. An innovator’s choice between Guangdong and Shanghai is not clear-cut, as both regions offer high levels of patent protection.

Hubei, a central province with its capital at Wuhan, is a rising innovation hub. Its provincial patent law is considered an “important pillar” of the local government’s implementation of the “Rise of Central China” strategy.187 This strategy, initiated by the central government, aims to bridge the economic disparity between China’s prosperous coastal regions and the less economically developed central regions, furthering balanced growth nationwide.188 Although Guangdong’s legislative process was an important reference point for Hubei’s government,189 it adopted slightly fewer patent protection measures than Guangdong did. Hubei’s local patent law offers government-funded patent applications that can assist innovators in obtaining patent protection. In terms of strengthening enforcement, it introduces legal aid mechanisms to help creators protect their rights.190 As for preventive measures, it also imposes review obligations on third parties,191 and it establishes an intellectual property credit evaluation system.192 Unlike Guangdong’s system, Hubei’s patent law does not introduce a multi-departmental collaborative enforcement mechanism, nor does it explicitly require administrative departments to incorporate advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, into patent enforcement. If innovators were only to consider local patent protection measures when choosing a location, Hubei’s slightly lower degree of patent protection might not be significant enough to make an innovator choose Guangdong or Shanghai instead.

Compared to the innovation hubs of Guangdong and Shanghai in the southeast coastal region, and the rising central province of Hubei, Qinghai, in northwestern China, is a less innovative province.193 Despite increasing investment and policy support for new energy industries like wind and solar power,194 Qinghai’s overall industry remains relatively undeveloped.195 Tibet, in southwestern China, ranks even lower in technological innovation.196 Dominated by agriculture, animal husbandry, construction, and tourism,197 Qinghai’s total innovation expenditure in 2021 ranked second to last among China’s provincial-level administrative regions at 2.67 billion yuan (approximately $421 million), surpassing Tibet’s 470 million yuan (approximately $74 million), but far below Guangdong’s leading 545.61 billion yuan (approximately $86 billion).198 In the same year, industrial enterprises in Qinghai filed a total of 1,354 patent applications, more than Tibet’s 100, but far fewer than the 340,935 filed in Guangdong, the leading province.199

Although Qinghai’s patent law shares the common goal of augmenting local enterprise competitiveness,200 its content diverges substantially from the patent laws in the previously mentioned regions. Similar to them, Qinghai’s patent legislation provides special funds and information retrieval services to aid innovators in applying for patents and safeguarding their rights.201 However, it deviates in terms of rights enforcement and infringement prevention, lacking the measures that Guangdong, Shanghai, and Hubei’s patent laws offer to bolster enforcement and stave off infringement. Tibet and its cities have yet to formulate local patent laws to enhance patent protection. Looking just at patent protection measures, Qinghai and Tibet appear less enticing than other provinces. This possibly could be one of the factors contributing to their lesser appeal in attracting innovative talent and enterprises. In 2021, Qinghai had 9,438 people engaged in R&D, ranking second to last among all provincial-level administrative regions in China, just above Tibet’s 3,219.202 In the same year, only fifty-four industrial enterprises in Qinghai were involved in R&D, more than Tibet’s three, but far fewer than Guangdong’s 32,938.203

V. Evaluating China’s Semi-Decentralized Patent Legislation Model by Comparing it with the U.S.’ Centralized Model

By extending legislative power to local governments, China’s central government has enabled them to establish their own patent laws, thereby creating a semi-decentralized patent system. The coexistence of national and local patent laws represents the fruits of a cooperative endeavor between the central government and local governments in structuring the patent system, where the central government takes the leading role. Local patent laws, while complementary, do not alter the requirements that the central government set forth. Rather, they modulate within the boundaries of the national law, guided by the central government’s directives, and adapted to the specific local circumstances.

This section aims to evaluate the benefits and potential challenges of this semi-decentralized patent system by contrasting it with the current centralized patent system of the U.S. It is important to note that determining whether a legal system is suitable for a country requires substantial local information. Making conclusive judgments about the patent systems of China and the U.S. goes beyond the scope of this paper. The purpose of juxtaposing China’s model with that of the U.S. is merely to highlight its characteristics and facilitate theoretical analysis, with the hope of providing researchers with some thought-provoking insights and policy makers with potential references for reform. Therefore, the conclusions in this section are preliminary and provisional.

A. Merits

Compared to the centralized U.S. patent legislation model, a significant feature of China’s semi-decentralized legislation model is that local governments cooperate in the building of the patent system by making local laws to meet specific regional needs, enhancing the adaptability of the patent system overall.204 Without local governments’ input, centralized legislation to maintain uniform patent law across the nation could, as Michael Carroll points out, entail “uniformity costs”—namely, under-protecting costly innovations and over-protecting those with lower innovation needs or alternative appropriability mechanisms.205 And like some other countries, China comprises a range of local development plans, traditions, and cultures.206 Granting legislative authority for patents to the local governments might be the ideal way to adapt to diverse local conditions. Part of the reason for this, as Friedrich Hayek pointed out, lies in the dispersed nature of knowledge.207 Informational deficiencies might keep the laws that the central government enacts from being responsive to local conditions.208 The semi-decentralized legislation model encourages participation, allowing provincial or city governments to use their local knowledge to make the legal system more adaptable to local conditions.

Another related benefit pertains to the geographically uneven distribution of industries. The U.S. has regional clusters of innovators in specific sectors, such as agricultural technology in California or orthopedic devices in Indiana,209 and so does China.210 Uniform national patents that the central government issues create incentives to develop innovations for broad market protection and monetization, but lack specific incentives for investing in innovations important to specific communities.211 Local governments can tailor their patent laws to cultivate regional clusters of innovators in specific sectors,212 or to encourage the pursuit of projects that directly enhance the well-being and quality of life of local residents,213 such as by providing stronger patent protection and enforcement measures. This approach can enhance investment in new technologies by promoting regional innovation clusters and supporting local public goods.214

Viewed from a dynamic perspective, the advantage of giving local governments patent legislative power lies in their ability to experiment with new rules through legislation.215 Such experimentation can lead to innovation within the patent system. In fact, according to John Duffy, the history of patent law underscores the importance of experiments in law.216 Local legislative power can facilitate the simultaneous experimentation of different statutory laws across regions, enhancing its efficiency of and, in turn, boosting innovation in law.217 Indeed, the ability to experiment with decentralized law is a characteristic and an advantage of federalism.218 As the late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis pointed out, “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”219 By contrast, centralized patent legislation requires that statutory experiments occur sequentially rather than geographically, leading to slower legal innovation.220 And when these experiments are not conducted simultaneously, interpreting the data from any innovation is challenging, as the lack of variation means that there is no proper control.221

The semi-decentralized model promotes innovation by enabling the testing of different approaches, generating a wealth of information about institutional reform.222 Local governments can conduct experiments with the new statutory rules that they create, and the knowledge that such experiments generate can in turn inform the legislation of other local governments as well as the central one. The value of this strategy became clear during China’s period of reform and opening up and continues to this day.223 As Deng Xiaoping, the second-generation leader in China, stated: “There are regulations that localities can engage in first, on a trial basis, and then after summing up and improving, [we will be able to] make laws that are applicable nationwide.”224 Xuan-Thao Nguyen echoed this view, highlighting the instrumental role of localities as laboratories of change, whose successful experiments in patent-law reform can profoundly influence both local and national legislation.225

The U.S. patent system faces challenges in fine-tuning patent legislation to meet specific local demands while simultaneously advancing regional trials of laws. However, this does not imply it is rigid. The court system can, to some extent, accommodate diverse local demands within the patent system. When adjudicating cases, judges can exercise discretion, interpreting statutory provisions in light of the unique circumstances of each case, including the regional context and the specific needs of the parties involved. Dan Burk and Mark Lemley have suggested that judges have thirteen “policy levers,” in other words, flexible legal standards within patent law, including the doctrines of utility, experimental use, and the level of skill in the art, that they can adjust to meet the peculiarities of cases, especially when technological differences underlie their uniqueness.226 These levers empower courts to integrate considerations of economic policy and industry-specific variations when applying overarching patent rules to particular cases. Intrinsically woven into the system, these policy levers allow judges to acknowledge the diverse features of innovation across various industries, hence contributing to a more customized enforcement of patent law.227 By harnessing these policy levers, courts gain the ability to adjust the application of patent law to accommodate the unique nuances and demands of a wide array of industries, ranging from chemistry to pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, semiconductors, and software.228 Moreover, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit can draw on regional appeals to establish precedents as a way of refining existing rules.

Some may argue that the judiciary alone suffices to enhance the adaptability of the patent system and conduct legal experimentation, thus making local patent legislative power unnecessary. However, it is essential to note that this model comes with several limitations. First, the system itself favors centralization, because the Federal Circuit has exclusive nationwide jurisdiction over patent appeals. Judge Randall Rader has already pointed out that the court’s exclusive jurisdiction creates less opportunity for “experimentation” with legal issues.229 Echoing this, former Chief Judge Paul R. Michel highlighted the Federal Circuit’s tendency to replicate old results based on prior precedents, thereby hindering the law’s ability to adapt to changing business and technological landscapes.230

Faced with the court system’s limited ability to engage in legal experimentation due to its centralized nature, Craig Nard and John Duffy have called for the establishment of a polycentric decision-making structure in patent law. It would emphasize the value of competition and diversity in legal systems and offer the potential benefit of such a “moderately decentralized framework,” which could allow for incremental innovation and experimentation.231 Echoing this view, Diane P. Wood suggests that perhaps the solution lies in removing the exclusive jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit.232 Under her proposal, litigants would have the option to submit their appeals to the Federal Circuit or proceed with litigation in the regional circuit where their claims were first presented.233 Such an arrangement would grant the Federal Circuit the room to leverage its specialized expertise, yet pave the way for a more expansive evolution of patent law, allowing fresh perspectives to permeate and flourish.234 This richer jurisprudential landscape would also provide the Supreme Court with a more comprehensive foundation from which to make its decisions.235

The second limitation is that courts can only the address matters that come before them. Thus, statutory law inherently constrains the range of issues. Furthermore, the cases that enter the litigation process might not cover the entire spectrum of local needs or concerns, whereas local legislation can comprehensively and specifically address a wide range of regional issues. From a timing perspective, courts generally address issues retrospectively, as they respond to disputes that have already arisen, while local legislation can proactively tailor patent laws to meet regional needs and prevent those disputes in the first place. Forward-looking rulings, such as those relating to cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence, might be difficult for the court system to generate in a timely manner. Legislation, on the other hand, allows local governments to construct forward-looking rules. One additional point is that litigation costs also influence the scope of issues that courts address. The high cost of litigation restricts the range of legal updates as most issues with low individual economic value will not enter litigation. However, when enough disputes involving low-value issues accumulate so that their collective value becomes significant, the courts might not be able to respond in a timely manner.

The third limitation is that legal reforms through the court system can lead to insufficient participation from stakeholders. Local stakeholders, especially those who have not instigated these cases, have limited opportunities to influence judicial interpretation directly. This is because courts base their decisions primarily on the legal arguments that the parties involved in the litigation present. Conversely, stakeholders can offer direct input that helps to shape local legislation, ensuring that patent laws reflect their priorities and needs. Some critics argue that the Federal Circuit’s patent jurisprudence has become isolated and disconnected from the technological communities it affects.236 Comparatively, when local governments have legislative authority, as is the case in China, local citizens can also advocate for legal reforms that are tailored to their specific needs by influencing local legislation through public consultations,237 expressing views to representatives,238 and collaborating with NGOs.239 This approach allows for more informed legislation. Moreover, Article 87 of the Legislative Law of China requires local legislators to make drafts public and to solicit the public’s opinions.240 Stakeholders can also influence legislation by providing comments.

B. Challenges

The principle of uniformity, often invoked as a justification for centralization, is widely recognized as desirable in various areas of law in the U.S., including the patent system. As John Duffy notes, “[t]he policy in favor of national uniformity in patent law has . . . ancient roots in the [U.S.’] law.”241 A uniform patent institution offers simpler rules, enabling businesses to rely on its protections more readily. Indeed, a nationwide uniform patent system obviates the complexities that arise when navigating multiple state patent systems, and so facilitates business investment.242 Uniformity by central government legislation often creates economies of scale, allowing for the application of rules and regulations across a broader area.243 When compared to the centralized patent law in the U.S., it is easy to see that one challenge, at least in theory, facing the semi-decentralized patent system in China is that the presence of multiple province-level and city-level patent laws that local governments made can lead to inconsistencies and variations in protection, potentially creating confusion and unpredictability for inventors seeking to navigate the complex legal landscape. Inconsistency and unpredictability can increase the cost of operations244 for both administrative agencies and private businesses.245

While concerns about legal inconsistency are understandable, the differences among local patent laws in China have not yet led to significant conflicts. As of this writing, there is no documented case of a dispute arising from inconsistencies in regional patent laws. Additionally, there is a noticeable lack of discourse among China’s legal academics and practitioners regarding the resolution of such potential inconsistencies. We can attribute this lack of conflict to two factors. First, the Chinese central government’s effective legislative oversight has been instrumental in mitigating potential disputes arising from the disparities in local patent laws. We can view local patent legislation in China as a diversity experiment for the patent system, one that the central government promotes and supervises.246 The central government, through the exercise of its legislative supervisory powers, plays a crucial role in eliminating inconsistencies in local legislation.247 Second, variations in local laws do not necessarily predicate disputes. For instance, both the governments in Guangdong and Shanghai have bolstered law enforcement248 and established preventive measures249 against patent infringement. 250 Such initiatives are unlikely to cause a clash with patent laws in other regions. They are consistent with national patent laws, and merely stipulate a higher standard within the permitted legal framework.

Despite the legal variations, it is crucial to recognize the inherent complexity resulting from differences among local patent laws, and the possible confusion that this might cause. Businesses, particularly those with operations in multiple locations, might have to bear additional costs to accommodate such legal diversity. Yet accurately quantifying these extra costs poses a significant challenge that goes beyond the scope of this paper. We should not, however, interpret the existence of these extra costs, if any, as an unfavorable outcome. After all, uniformity is not necessarily synonymous with quality or desirability.251 The benefits that legal diversity confers could potentially offset the associated increase in costs, although it is premature to draw a definitive conclusion on this point due to the lack of empirical data. Furthermore, given that many cross-regional businesses often rely on specialized legal counsel for guidance,252 the existence of multiple local patent laws might not significantly impede their capacity to innovate or protect their patent rights.

It is worth noting that certain local legislations might potentially enhance, rather than reduce, the consistency of the patent system’s operation. Under the guidance of the central government, local governments in China have established mechanisms within their local patent law, or more broadly, local intellectual property law, by which to enhance coordination among local patent departments.253 To date, thirteen local governments (twelve provinces and one city) have done this. For example, the local laws of Beijing and Hebei incorporate cooperative mechanisms that bolster regional patent rights protection in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region.254 These mechanisms facilitate the cross-regional transfer of case leads, investigation and evidence collection, and enforcement, thereby streamlining the administrative application of patent rights across a region that spans the jurisdictions of several local governments.255 The establishment of such mechanisms not only signals a commitment to addressing potential discord in the operation of local intellectual property departments but also suggests a reduction in the operational costs of the patent system by fostering an environment conducive to cross-regional collaboration.256

Another concern regarding local patent legislation is that local patent laws might not align with the patent standards of the TRIPS Agreement, which stipulates minimum requirements for member nations of the World Trade Organization.257 Compliance with the TRIPS Agreement under China’s semi-decentralized patent system depends on two conditions. First, the national patent laws do not offer a level of patent protection lower than the TRIPS minimum. In terms of legislation, by 2005 China’s national patent laws have provided patent protection that meets the requirements of international treaties.258 Second, local patent laws should not degrade the level of patent protection that the national patent laws offer, as these are consistent with the TRIPS standards. The current Legislation Law requires that local laws must “not conflict with the Constitution, laws and administrative regulations.”259 Reducing the national patent law’s level of protection would constitute such a violation. The law gives the NPC Standing Committee the authority to review local legislation and mandate revisions to or annul local laws that contradict higher-level laws.260 To date, there have been no instances of the Committee abolishing a local patent law for this reason. This Article’s findings suggest that local patent laws generally provide protection levels superior to those of the national system. Therefore, at least for now, it seems unlikely that local patent laws in China will violate the TRIPS Agreement.

Another challenge to this semi-decentralized model is the potential for efficiency losses due to local legal experimentation, an issue that is particularly relevant in China. In the context of local competition, local patent laws often incorporate two types of measures. Firstly, local governments use their own finances to fund businesses applying for patents. For instance, Article 4 of the Fujian Patent Law stipulates, “The local people’s government should increase funding for the promotion and protection of patents, raise funds through multiple channels, and use them to support patent applications.”261 Secondly, local governments make patents a primary consideration when granting financial benefits to businesses, such as government funding, preferential access to government procurement, and tax benefits. For example, Article 12 of the Fujian Patent Law dictates that “government procurement and other purchases using fiscal funds shall give priority to the purchase of patented products under equal conditions.”262 Businesses engaged in innovative activities and keen on obtaining patent protection undoubtedly find these measures attractive, as government financial support at the application stage reduces the cost of patent acquisition, while financial benefits granted on the basis of patents can put companies in a financially advantageous position compared to their competitors.

However, research shows that the implementation of these two types of measures can encourage businesses to engage in rent-seeking behavior. With no or minimal investment required to apply for patents, businesses might apply for patents for non-innovative, low-quality technologies.263 Some applicants, in order to secure government supportive funding for patent applications, even divide a single application into multiple ones.264 Studies indicate that the practice of local governments subsidizing patent applications has led to a decrease in the patent quality.265 This not only results in a waste of government financial and human resources at the application stage266 but also leads to increased administrative costs for subsequent patent management.267 For companies wishing to enter the innovation field, navigating a dense thicket of low-quality patents can also lead to waste of resources that they could otherwise have used for innovation.

The resource wastage caused by government funding for patent applications may be exacerbated by local governments’ heavy reliance on patent signals for fiscal resource allocation,268 even when overall patent quality is not high.269 Empirical studies show that local governments focus mainly on the number rather than on the quality of patents to determine tax benefits and financial subsidies. 270 But, as Clarisa Long points out, signals from patent numbers are ambiguous, do not necessarily reflect a company’s innovative capabilities, and are subject to manipulation.271 A local government’s overreliance on these signals might cause it to be misled. Moreover, these measures can produce distortion effects. Research shows that firms have overinvested in activities to obtain patents that attract government funding, resulting in the misallocation of resources that should have been directed toward production.272 In addition, these measures might also distort market competition. For example, the Fujian Patent Law requires the government to prioritize the purchase of patented products.273 However, being covered by a patent does not necessarily mean a product is of high quality. Low-quality products with patents might squeeze out high-quality, unpatented products in the competition for government procurement. In sum, while the involvement of local governments in constructing the patent system can foster institutional experimentation and innovation, institutional innovation is not cost-free. After all, a new rule does not necessarily mean a good rule. The benefits of institutional experimentation and innovation are partially, and hopefully not entirely, offset by the costs of experimentation failures.

Scholars have also voiced concerns that competition among local jurisdictions might lead to the use of local patent legislation for protectionist purposes,274 consequently diminishing social welfare.275 While local competition can stimulate sound legislation, it can also result in wasteful strategic behavior.276 Stakeholders within a locality might seek trade barriers that deter external competitors from penetrating the local market, to the detriment of outside businesses or industries.277 This concern is relevant in China, where local patent laws encourage patent rights holders to align their patents with local technical standards, a practice that could yield anti-competitive effects and result in efficiency losses.